Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion4

Reimagining Agility with Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

May 23, 2021

May 23, 2021

This report explores the intersection between agile, business agility, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I).

| DE&I report downloadable graphics (ZIP, 2.2MB) |

|

| DE&I summary article (PDF, 14.8MB) |

Throughout 2020 and early 2021, we interviewed and surveyed over 400 professionals, coaches, and leaders. We collected their experiences and insights on how agile and DE&I overlap, as well as the state of inclusivity and equity inside agile organizations. We also collected their professional recommendations regarding how we can improve agile ways of working by considering the impacts of DE&I. This report summarizes our findings.

Findings indicated:

This report finds that DE&I and agile share common values and principles. When these values align within an organization, they improve working conditions and business outcomes. However, these opportunities are being overlooked by agile teams, leaders, organizations, and industry bodies alike.

Recommendations include:

Agile is a mindset and way of working that allows teams to leverage their unique skills and deliver maximum value to customers in a fast and adaptive manner. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) encompasses the efforts any institution takes towards creating a welcoming and supportive environment for all their employees, and customers. These two concepts go hand in hand.

When employees feel supported and embraced by an equitable, inclusive workspace, they will naturally be more able to work to their full potential and improve business outcomes. Likewise, any method of working which relies upon employees bringing all their expertise and lived experience to bear should center inclusion and equity in its systems and structures.

There are many ways in which the values and principles of agility overlap with concepts of DE&I. One of the core principles of the agile movement is to value individuals and their interactions over processes and tools. This reflects the core tenets of DE&I, which asks organizations to examine and recognize the individual backgrounds and circumstances of team members. Both agility and DE&I require organizations to understand what people need to thrive, and forces organizations to examine whether their working environment is designed to be inclusive and equitable, rather than assuming those mechanisms exist by default.

And yet, agile and DE&I are not often considered symbiotic, or integrated side by side into workplace transformations.

This report, based upon over 400 interviews and surveys, explores instances of exclusion and inequity in agile organizations. It discusses the collective opinions of agile professionals, employees, and those who have been exposed to agile organizations regarding the relationship between the two, and provides recommendations for organizations, professional bodies and individuals wishing to improve inclusion and equity inside their communities, and in turn improve outcomes for their customers.

Agile is the ability to create and respond to change. It is a way of dealing with, and ultimately succeeding in, an uncertain and turbulent environment [Reference: Agile Alliance].

Agility is the state or quality of being agile, nimble; the power to be quick moving and active.

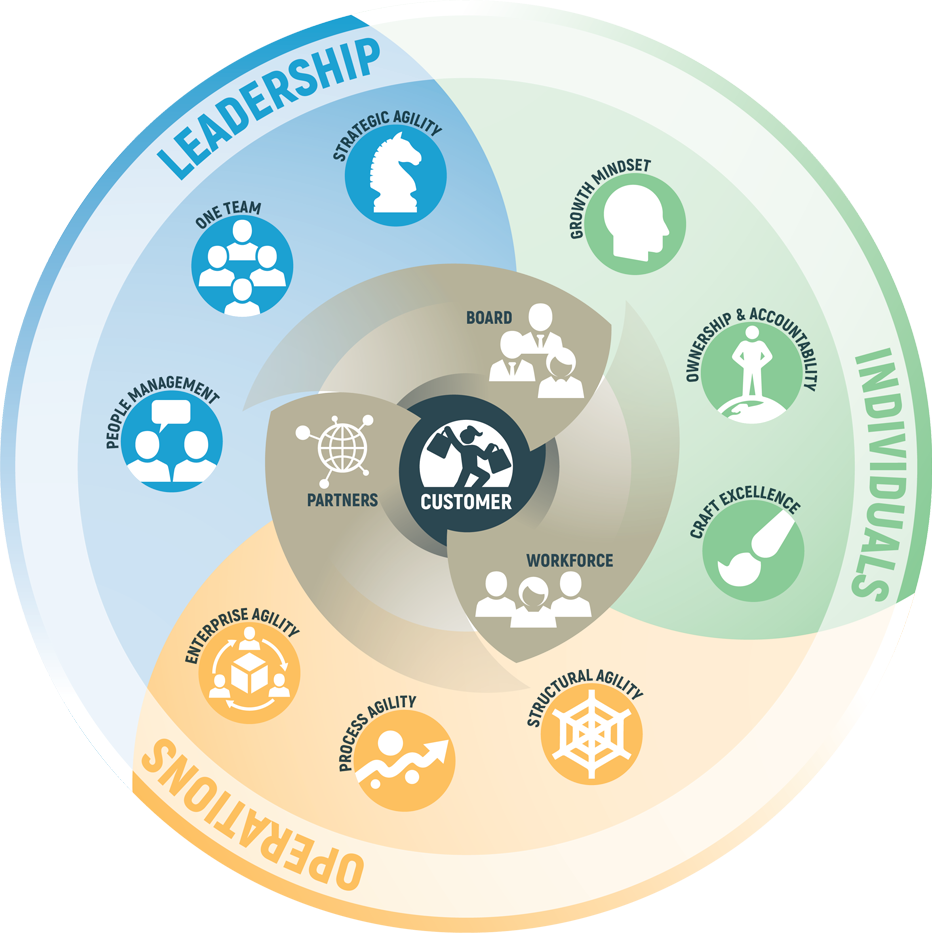

Business agility is a set of organizational capabilities, behaviours, and ways of working that afford a business the freedom, flexibility, and resilience to achieve its purpose, no matter what the future brings [Reference: Business Agility Institute].

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) is a broad approach which includes all efforts made by organizations to ensure they are creating and maintaining an environment that is welcoming and supportive for all people.

For the purposes of this report, we will define each individual term as follows.

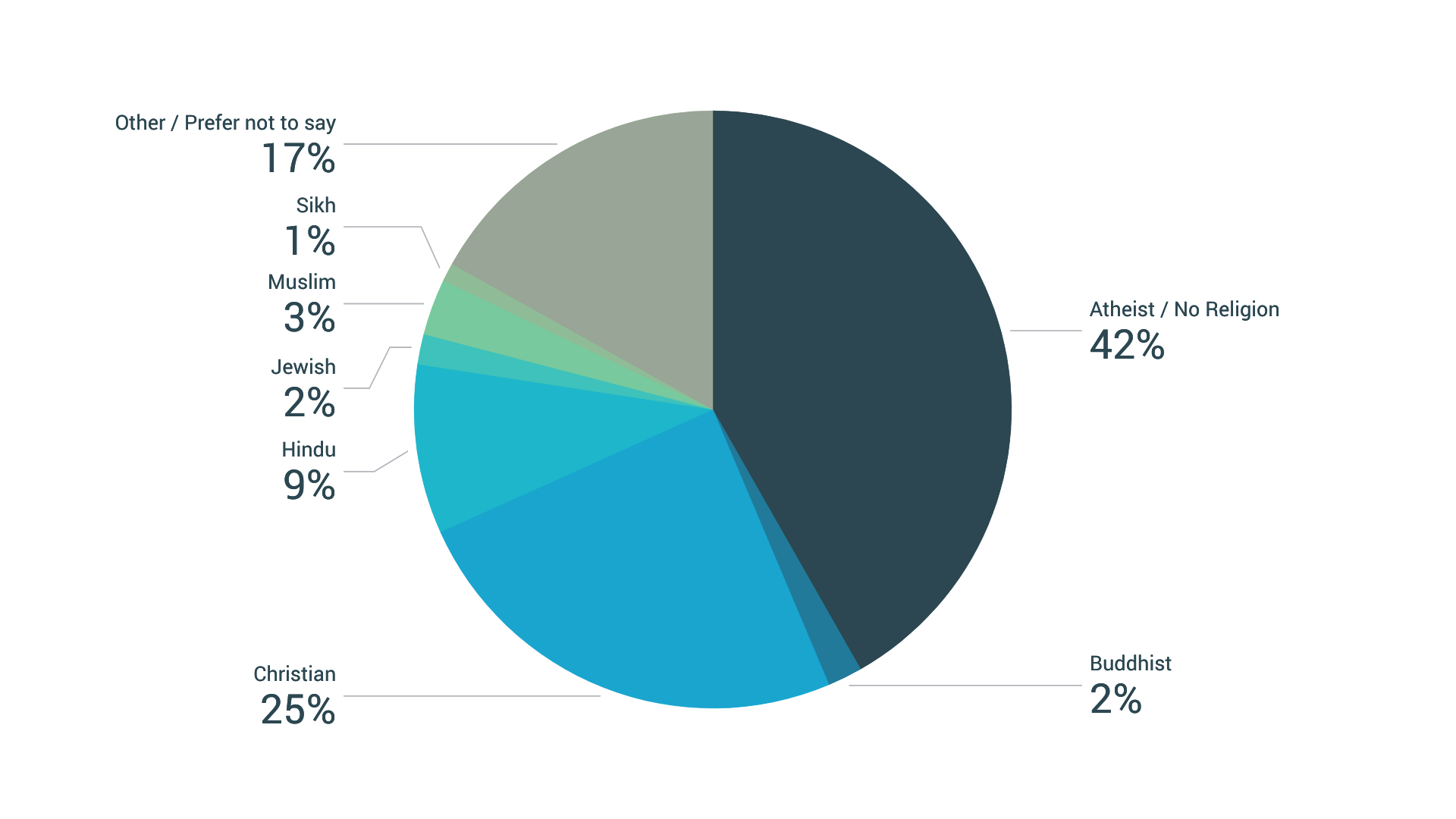

Diversity is the mix of all of us. It includes demographic differences, backgrounds, multiple identities and unique experiences, perspectives, knowledge, abilities, ideas and more. It refers to all people and differences among us. Diversity includes aspects such as gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, cultural background, nationality, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, age, physical and mental abilities, religion, education, marital status, language, personality types, life experiences, physical appearance, working preferences and different ways of thinking.

Inclusion is the act of welcoming and applying the mix created through diversity. Inclusion is focused on fostering the structural systems, processes, culture, behavior, and mindset that embrace and respect all people and all our diversity. Inclusion exists when all people are valued and able to participate and contribute to their fullest.

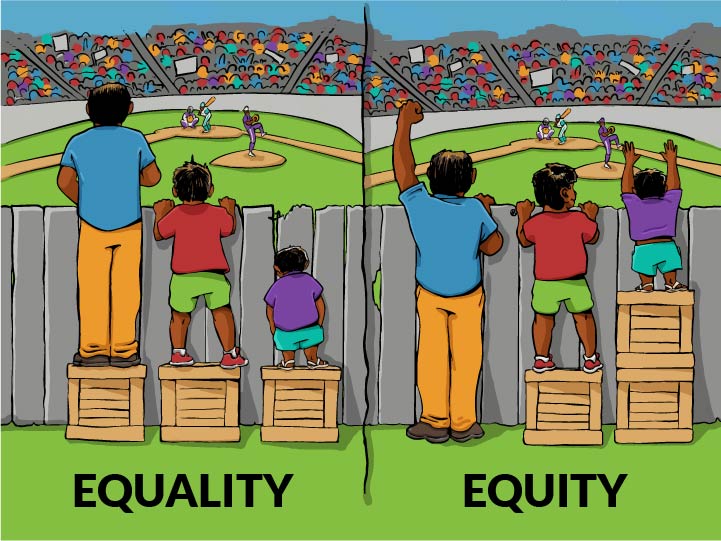

Equity applies a structure of fairness to the diversity mix. Equity ensures that all people have equal access to opportunities and fair treatment and eliminates discriminatory practices, systems, laws, policies, social norms, and cultural traditions. In contrast to equality, which applies the same resources and support structures to all, equity requires resources and support structures to be tailored to the individual, providing everyone in the diversity mix an equality of opportunity and outcome. Equity also encompasses a balancing of power and correcting where inequality exists [Reference: Nielsen, T. C., & Kepinski, L. (2016). Inclusion nudges guidebook].

Figure 1: Interaction Institute for Social Change

Artist: Angus Maguire.

In November 2019, Mark Green - founder of Agile Inclusion Revolution - presented a talk entitled A Spotlight on Diversity and Inclusion, which discussed the issues faced by the integration of inclusion and equity into the agile framework. The talk explored the misalignment between agility and DE&I, and the resulting inequity and exclusion unwittingly propagated by dominant groups.

Business Agility Institute co-founder Evan Leybourn attended the talk and followed up with Mark, proposing further research that would gather insights into the unity of agility and DE&I.

A primary volunteer research team assembled in April 2020 and spent twelve months engaging and analyzing hundreds of individuals and organizations around the world. Insights were gathered through surveys and online interviews covering a multiplicity of industries and a wide variety of experiences.

At the outset of the research process, the teams had two key hypotheses:

It is necessary to clarify key parts of these hypotheses.

There is the potential for agile organizations to have developed DE&I frameworks which improve inclusive and equitable environments for their staff, customers, and communities. However, it is still possible that exclusion occurs even in the most DE&I-focused agile organizations, or as the direct result of agile practices and cultures.

There is no absolute way to measure performance between organizations without complete access to private business metrics. Additionally, it is difficult to correlate cause and effect, or determine which sets of metrics are more or less important in terms of gauging overall performance.

For this research, alternative methods of comparing organizations were determined. First, to measure performance in terms of the perception of respondents inside those organizations: for example, asking whether they felt situations surrounding DE&I had improved or worsened after agile transformations. Second, to measure performance from a broader societal perspective, by comparing an organization’s performance against common standards of what is considered inclusive and equitable for staff, partners, suppliers, and customers.

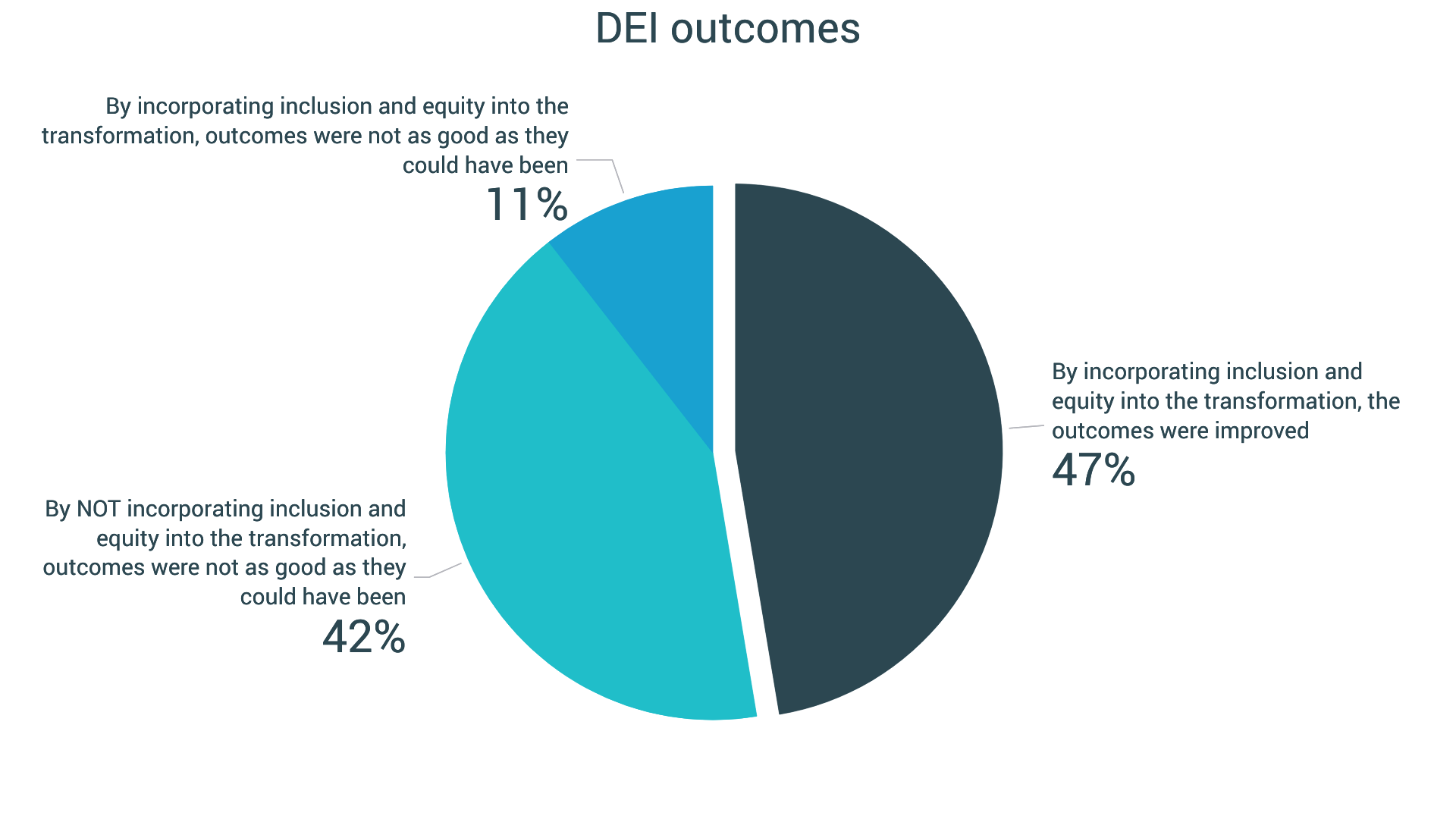

Results from the collated research indicated that, as per our first hypothesis, agile organizations are currently (consciously or unconsciously) perpetuating systems of exclusion and inequity and will continue to do so unless DE&I is explicitly encoded into their agile culture and ways of working. As per our second hypothesis, respondents also believe that agile organizations with embedded DE&I would reach higher levels of performance, as they were more able to leverage the skill sets of employees, understand their diverse customers, and remove barriers to success.

One of the core tenets of agility is to create a system of continuous reflection, ideation, and improvement, and this is equally relevant to the field of DE&I. This report will provide organizations and individuals with the scaffolding to help them critically examine their own policies, consult with diverse groups and policymakers, and embrace new opportunities for true inclusivity and equity. It is the hope of the research team that the research, insights and recommendations gathered in this report will serve as the foundation of future action in the field of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in agile workplaces and communities.

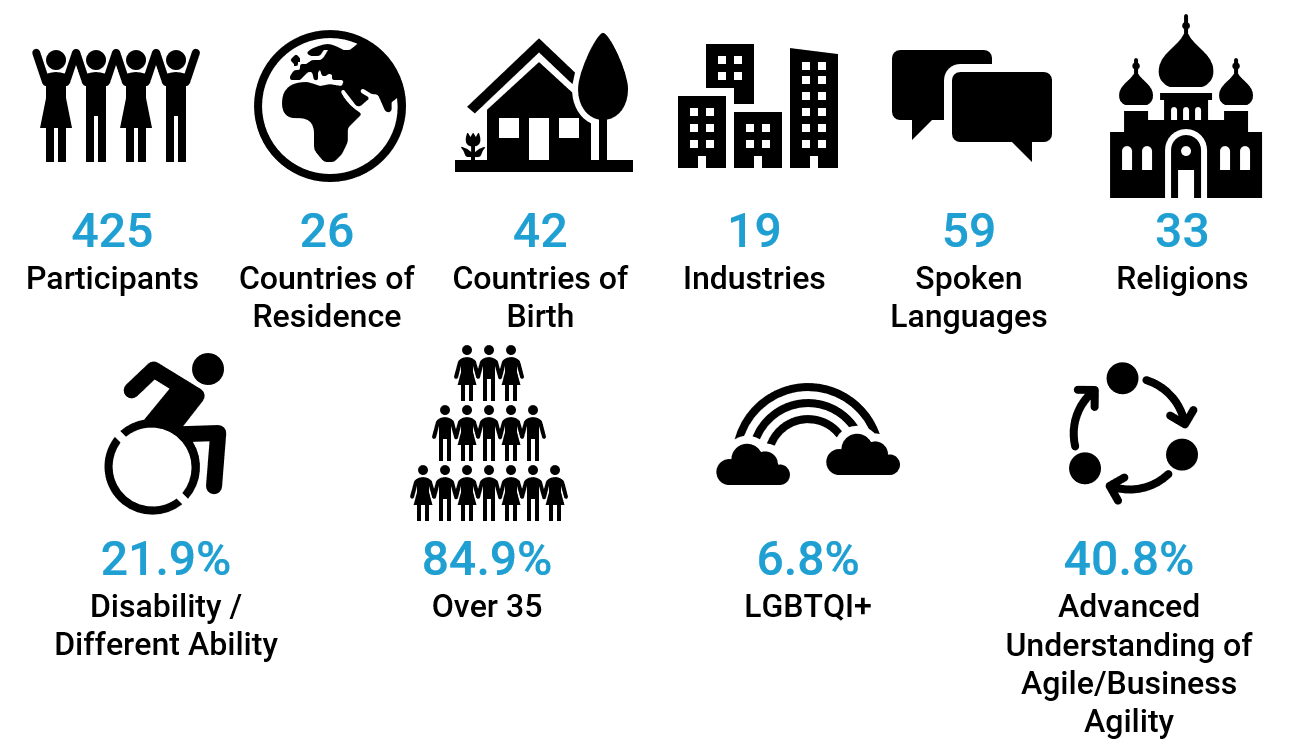

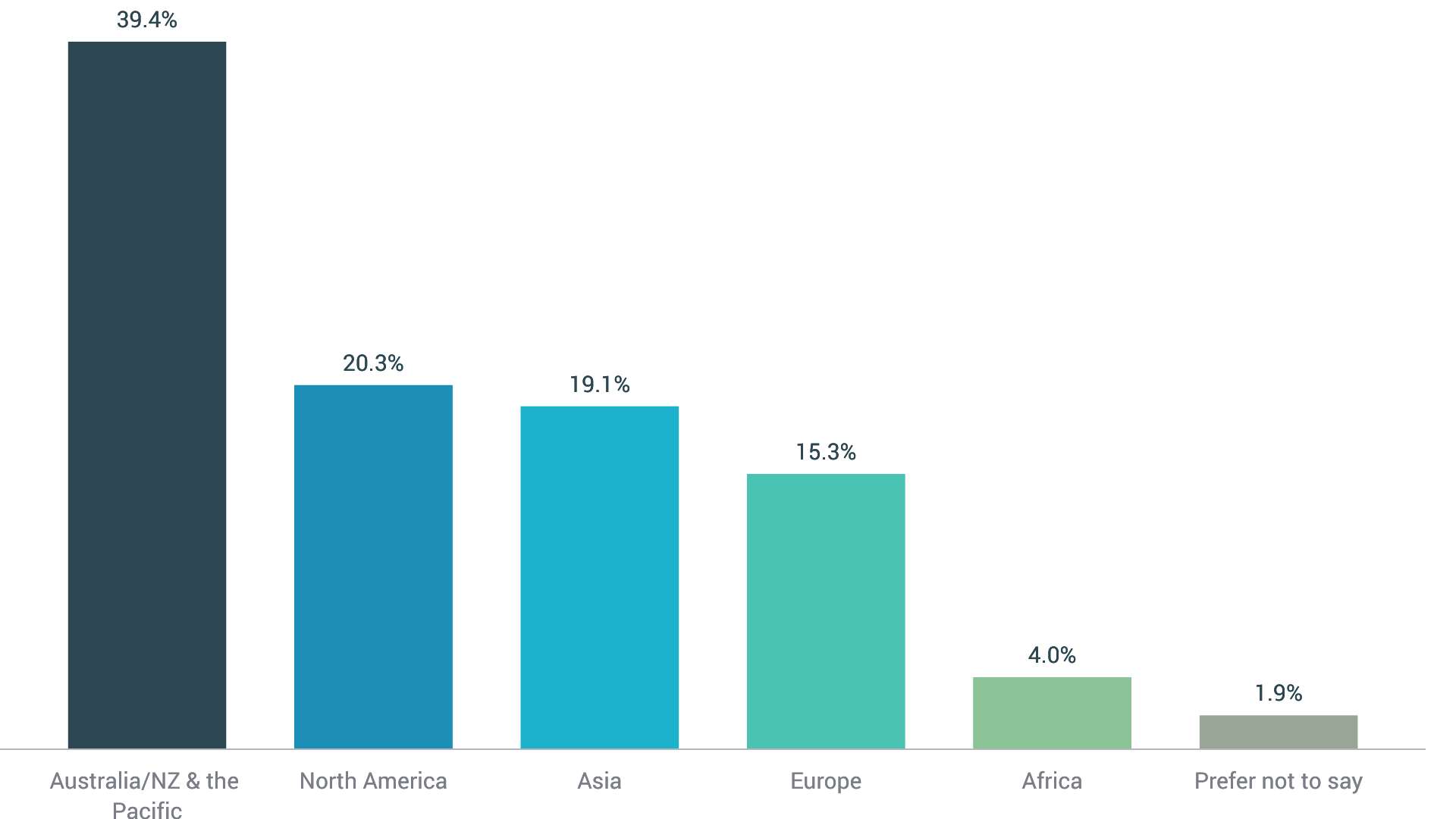

Beginning in July 2020, the research team heard from 425 individuals spread across 26 countries, of which around fifty percent were based either in the USA or Australia. This is likely a result of the demographics of the networks in which the primary researchers operated, as well as the higher percentages of agile organizations in those countries.

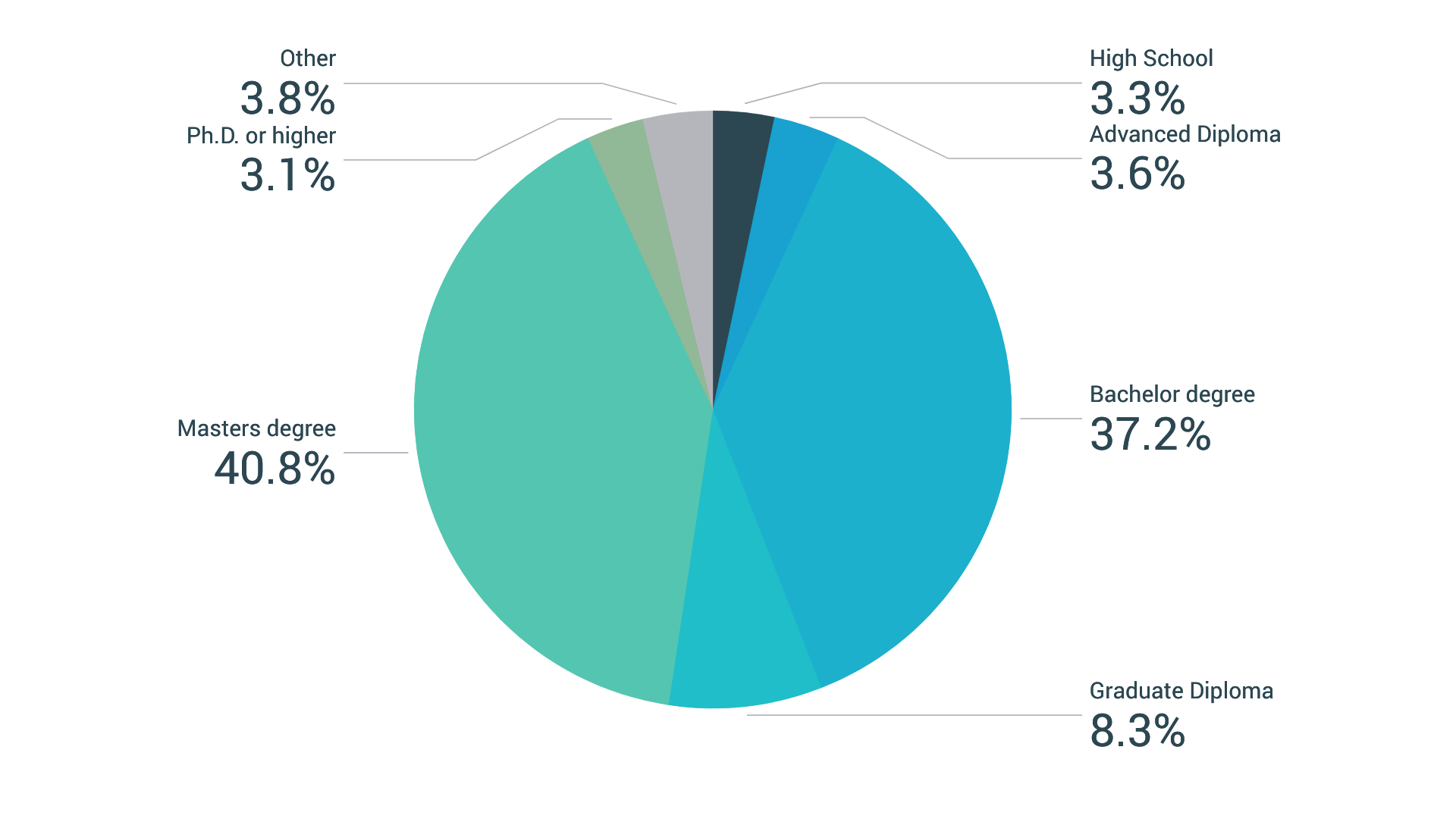

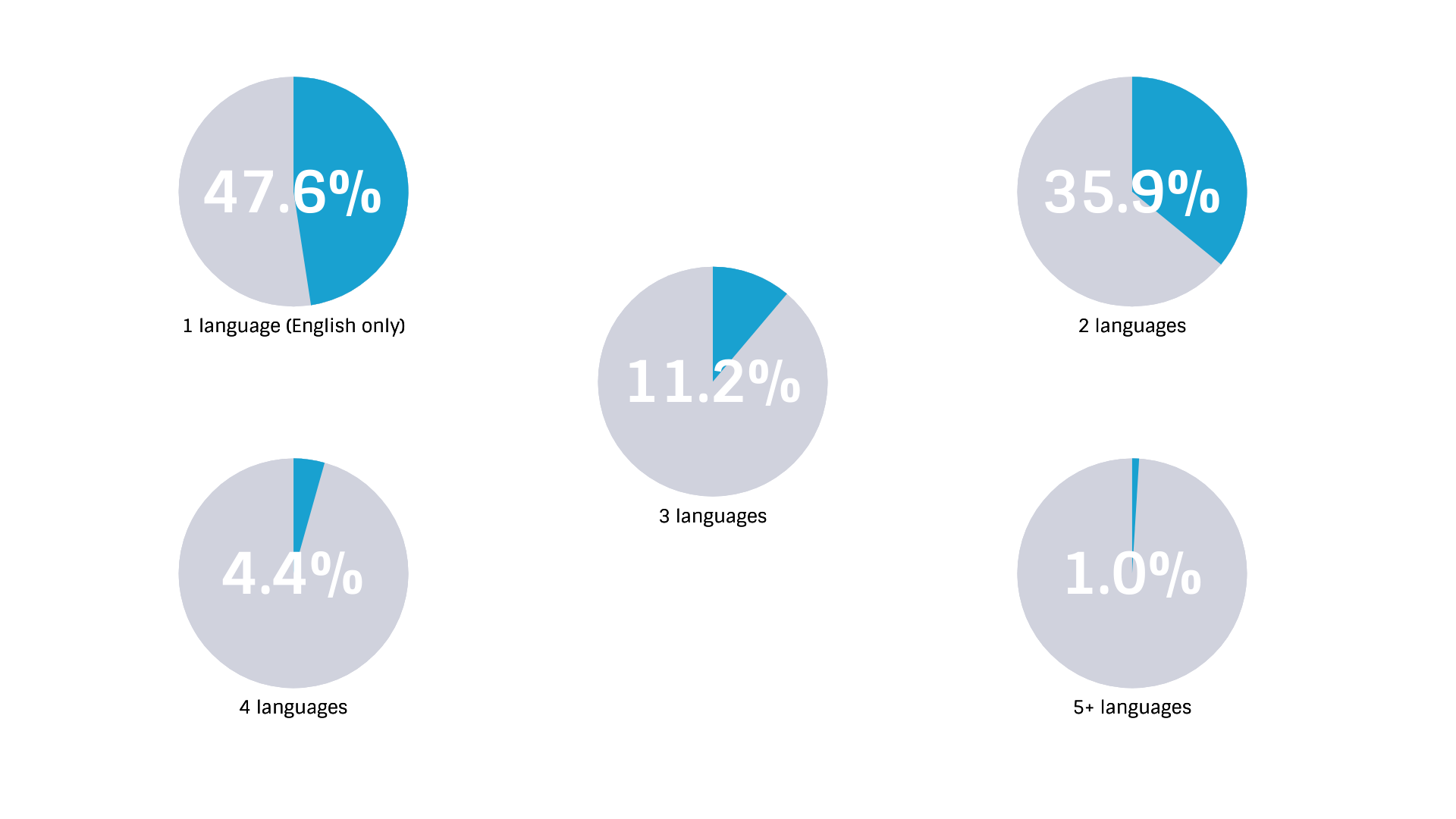

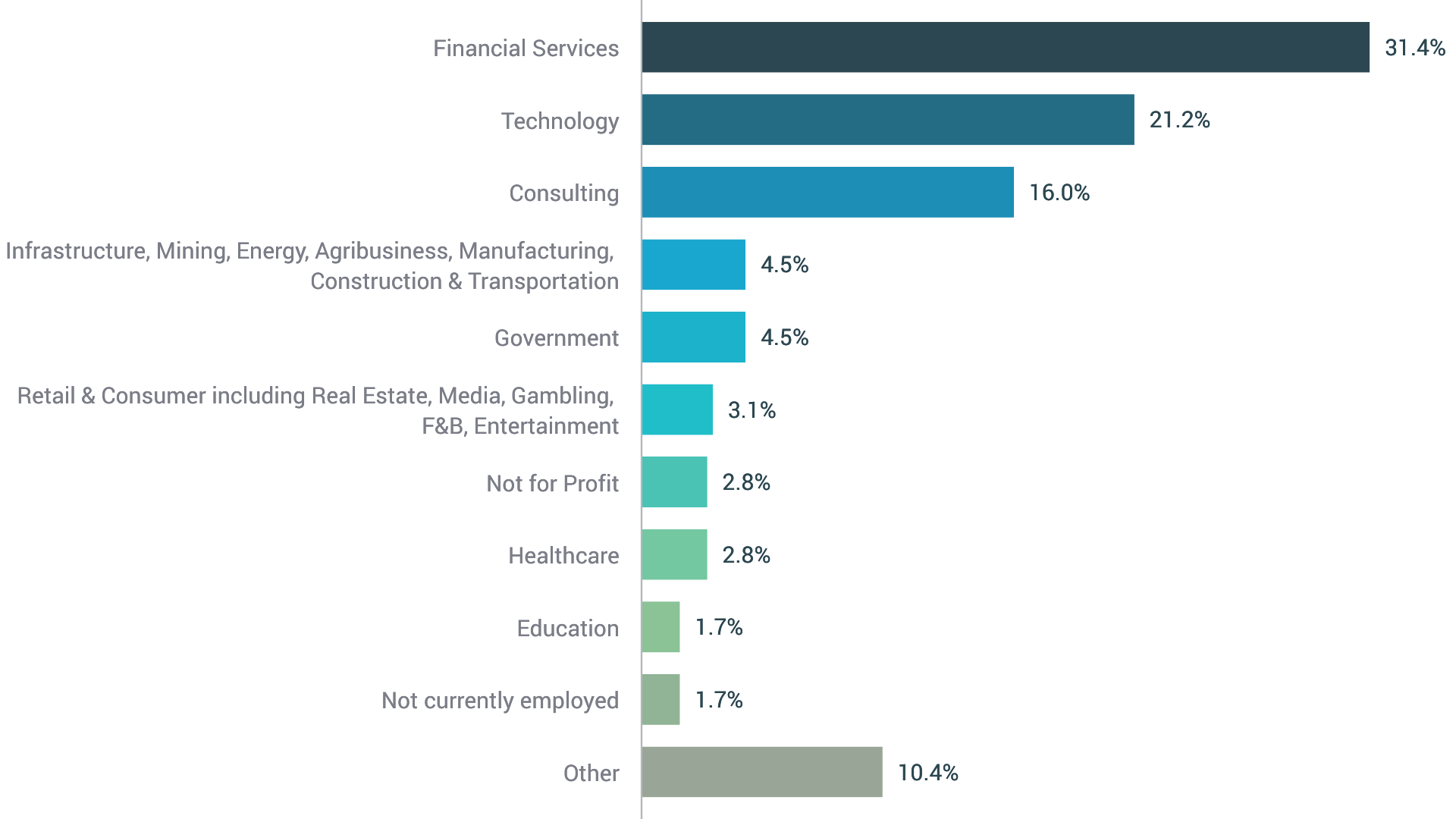

Subjects tended to have bachelor’s degrees at a minimum, possibly because many agile organizations seek team members with Higher Education, and possibly because survey targeting may have focused on team members in high-level roles. More than half of all participants were bilingual. Around 50% of participants worked in either the Finance or Technology sectors.

Responses from men and women were evenly spread. 84% of respondents identified as straight and 7% as LGBTQI+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, and Intersex). This broadly reflects social demographics but should not be taken as evidence that employment inside agile organizations is already at or near gender parity. Rather, it should be noted that people from minority and marginalized groups may be more motivated to take part in research studies where they are able to express their experiences of inequitable working conditions, which could cause a skewing of respondent statistics.

Of all respondents, 57% were currently working in an agile organization. A further 22% were working as partners to agile organizations. This spread of responses among agile and non-agile organizations was essential to capture a wider array of impressions and insights.

Of significance to this research were the number of responses which reported discriminatory circumstances in the workplace. These included issues of disenfranchisement, lack of support, prejudicial perceptions of disabilities, mental wellbeing concerns, personality types, and more. This made it apparent that many ways of working considered suitable for most employees are actually problematic for a proportion of the workforce.

Due to the restrictions on travel and face-to-face contact imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, responses were primarily gathered both via online interview and survey. Respondents were asked to complete either an interview or survey but not both, resulting in ≈120 hours of remote interviews and 307 individual responses to a fifteen-minute online survey. Both surveys and interviews were anonymous, and the questions asked in each were slightly different to account for the method of delivery.

The research team aimed to amplify the voices of less dominant groups, to treat every voice and opinion as vital, and every lived experience as valid. As such, the team connected with as wide a spectrum of respondents as possible.

These included people working both inside and in partnership with agile organizations, people with both extensive and minimal understanding of agile techniques, people who were working in both agile and non-agile roles, and people who had previous agile experience but were not currently working in agile organizations. In addition, and with their permission, a broad investigation of ten separate organizations was undertaken; interviewing staff from diverse functions to understand different perspectives on agility and DE&I from within the same organization.

Survey and interview questions explored experiences of agility, diversity, equity, and inclusion as related to working inside or alongside agile organizations, and as well as their impact upon the perceived customer experience.

It is important to acknowledge that the agile ecosystem, as well as the larger organizational ecosystem, does not accurately reflect the diversity of society as a whole. Many marginalized groups remain under-represented across all industries and organizations. As such, the research team entered the process with the understanding that the voices of some marginalized groups would be drowned out if the research focused on ‘majority’ answers or interpreted broad consensus from non-marginalized respondents as conclusive. To protect against the dampening of marginalized respondents, every response was regarded as equally important, regardless of whether those experiences ran counter to the majority.

Finally, the research team believed that using the gathered interview data as a method of ranking inclusiveness or equity within organizations would be divisive and inaccurate. Since no organization can be completely inclusive or equitable, ranking one organization as more inclusive than another would require the valuing of one individual’s experiences as more or less important than another. It is only possible to state that inclusion has improved or deteriorated in an organization or sector if initiatives have improved or worsened the conditions for everyone.

It is important to acknowledge potential gaps in the research.

While the research team recruited many people who were eager to engage, either through surveys or online interviews, there were many more groups from diverse demographics who did not believe they had the necessary knowledge of agile to adequately contribute. This may be because those groups had been previously excluded from agile organizations and teams.

Some potential reasons for this exclusion are:

Additional skewing may be attributed to the contact networks of research teams. Some respondents were sourced through direct contact with their employer organizations, weighting the pool of respondents towards those with pre-existing connections to research networks, established organizations in developed nations, or organizations known to the Business Agility Institute.

In addition, it is impossible to avoid some level of bias in the analysis of responses as the research team is staffed primarily by professionals in both the agile and HR industries. This is, in essence, an industry marking its own homework. Respondents already working inside systems supported by the same practices and cultures they were critiquing may have felt reliant upon or even indebted to those practices and cultures, resulting in skewed responses.

In addition, agile is built upon democratic values when it comes to discussion and decision-making, but democracy is not equivalent to equity. If marginalized people in the targeted industries felt unable to be truly heard due to their opinions clashing with the democratic majority, because existing systems have conditioned them to answer in certain ways, or because they felt uncomfortable sharing certain truths with a stranger, their inputs may have been missed.

It has also been noted that people from marginalized groups, as well as people who have experienced societal discrimination, sometimes lower their expectations regarding standards of inclusion and equity in the workplace. Understandings of what should be can clash with understandings of what is perceived as feasible, especially in cultural settings where Diversity, Equity and Inclusion are still unfamiliar concepts. As such, the gap between what kind of action is acceptable to the majority and what could be possible has undoubtedly skewed responses.

Respondents in the dominant group of their respective societies and cultures are also less likely to see issues with inclusion and diversity - as members of a privileged majority, some issues raised by marginalized respondents may be invisible to them (or if not invisible, acceptable). In turn, this affects the manner in which respondents viewed the necessity of DE&I action. For example, some respondents reported that they believed the first step in creating an inclusive environment was disclosure, essentially placing the burden of change upon the marginalized individual. This mindset stands in opposition to the core concept of inclusion, which places the responsibility of creating an inclusive environment on the organization.

Given the breadth of questions contained in the interview and online survey, most respondents focused their answers on topics they were familiar with - either through their own experiences of marginalization, or their own efforts to create and maintain DE&I in the workplace. It can thus be assumed that some respondents would have an inherent level of bias towards the significance of their own marginalizations, or the successes and failures of their own DE&I efforts, which may have influenced the lens through which they interpret DE&I as a whole.

A lack of common understanding and consensus regarding the creation of diverse, equitable and inclusive environments persists, both among leaders and individuals. The two most common are.

A misalignment on the definitions of equity versus equality. Equity in an organizational context refers to the creation of an environment where the individual and unique needs of every team member are met, allowing all to reach equal levels of success. Equality, by contrast, is defined as the state of being equal in status, rights, and opportunities. In an organizational context, this often describes systems and situations where every team member is provided with the same opportunities and allowances, without accounting for individual circumstances.

Little consensus on the definition of inclusivity. Understandings of what is and isn’t acceptable in the workplace differ between cultures, nations, and political climates. Respondents from different communities might believe they work in highly inclusive environments, while responding through a unique cultural lens in which the marginalization of certain identities - for example, of gender and gender identity, sexuality, nationality, disability, or religion - is socially acceptable, or even made explicit in law.

Without a consensus on what is required to create equity and inclusivity in the community, it is difficult to find consensus on what environment could be considered truly equitable and inclusive.

Both agile and business agility may be viewed as a collection of systems and processes that help teams and organizations deliver better outcomes for their customers.

However, it is more accurate to describe them as a mindset as well as a way of working which enables people to reach their highest potential by creating systems of self-organization, self-actualization, and enablement, which in turn makes organizations more adaptable. Regardless of the approach taken to achieve it, people are the core of agile.

Tools and processes synonymous with agile - Scrums, Kanban, etc - are not actually inherently agile. Rather, the ways in which those tools and processes enhance the lives, communication, collaboration, and working conditions of teams forms the core of agility. This reflects the values of the agile manifesto, which states:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work we have come to value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

Interaction, collaboration, and helping every team member reach their potential, are the not-so-secret sauce that makes agile work. These values should overlap and enhance the core tenets of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. However, research demonstrates that this is not currently the case in practice.

The agile manifesto, along with other industry models, implies a relationship between agile and DE&I. In fact, the agile manifesto’s first value of individuals and interactions over processes and tools implies that, for agile to work, DE&I must be a core component.

Despite this, there is no explicit connection between the two. The implication that agile is based around people, culture, customers, and values, and therefore agile must find worth in diversity, is not borne out by research responses: the most common response when discussing the intersection between agile and DE&I was;

“I haven’t thought about it.”

This creates the potential to assume that agile ways of working are organically doing the job of DE&I and to overlook the needs of others.

Flaws in the intersection between agile and DE&I were noted by multiple respondents. Respondents stated that, while they believed inclusion and equity were critical to agile outcomes, the organizations in which they were employed (or had previously been employed) were underestimating the business benefits of DE&I and not putting enough explicit focus on achieving equity and inclusion. Respondents also believed agile practices could benefit the creation of equitable and inclusive work environments, and that organizations were short-changing both their DE&I programs and their agile transformations by not leaning into the connections between them.

It’s possible that these connections were missed in respondent organizations because those in leadership positions were also those in the majority or in cultural positions of power. As a result, the decision to not explicitly connect agile and DE&I through policy may have been made because the benefits of DE&I - to employees, customers, and business outcomes - had not been experienced, understood, or believed.

Another possibility is that, in these organizations, senior management trust that their existing HR policies conform to government legislation regarding equal opportunities in the workplace. While this legislation contributes to creating equitable and inclusive environments, it is not the sole, key driver in creating and maintaining true workplace equity.

By sidelining DE&I, organizations are focusing on agile processes and tools at the expense of agile mindsets. By assuming that these ways of working are supporting DE&I well, exclusion and inequity can continue under the radar. This ultimately disempowers team members, stifles innovative thinking, impacts employee’s wellbeing, reduces outcomes, and leads to missed business opportunities.

To understand how exclusion and inequality is being perpetuated in agile organizations, and to see the ways in which DE&I can enhance organizations and help them outperform their contemporaries, it’s first necessary to discuss why diversity is important, and why many of our understandings about diversity in the workplace are misplaced.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion requires employers and employees alike to work to understand and create a more welcoming environment for people of all demographics. In turn, identifying and solving issues contributing to exclusion and inequity requires an understanding of differences in cultural and social norms, local and international laws, and general education on the needs of diverse and marginalized people. But a lack of understanding, coupled with varying definitions of what DE&I entails, has led to many instances of exclusion and inaction.

Therefore, the first step for anyone seeking to improve inclusive workplaces is to admit that their knowledge is naturally incomplete. That their understanding of DE&I will always be a work-in-progress and that they must challenge themselves as much as they challenge others. Only by understanding these differences will it become possible to create a truly inclusive and equitable agile framework.

Lived experience is the primary influence on any person’s belief systems. Lived experiences can be shaped by local culture, race and ethnicity, levels and structures of education (both formal and informal), gender (and cultural experiences associated with gender identity), countries of origin as well as countries of residence, sexuality, abilities and disabilities, socio-economic circumstances, employment histories and working conditions, and so on. All these factors contribute to differences in interpretations of DE&I. As such, it is vital for everyone involved in the development of more inclusive and equitable environments - including the research team compiling this report - to acknowledge that bias exists in everyone, and barriers to understanding will always exist between individuals.

“But there's still people who practice racism in a very passive way. So, they don't speak about it. You don't hear them. But there's passive execution of racism, gender inequality as well… It's deeply ingrained in the patriarchy belief and in that whole racism thing that people have been brought up with. So that is still, for me, a huge problem.”

These barriers slow the creation of better working environments. For example, manifesting as resistance to change, because innovation can serve to disrupt a system in which the majority are thriving. It can be just as dangerous if a person in a position of authority believes that no such barriers to understanding exist, and that they understand the structures required for true equity and inclusion better than the marginalized people they claim to represent. This can lead to DE&I approaches which only service to reinforce the status quo or are too narrow in focus.

Due to these fundamental differences in worldview and lived experiences, it is unlikely that a true consensus will ever be reached regarding the definitions of diversity, equity, and inclusion, or the actions required to create a truly equitable environment.

Some specific instances of bias in the workplace reported by respondents include:

"It is quite difficult for me to adapt [to agile]. I work onsite and it is really hard for me to pray 5 times a day because most [other] people don’t have those needs."

“I was the first person with visible disability in the office. They recognized my needs. For a successful outcome empathy is required not sympathy."

Discussions around DE&I are not necessarily equitable or inclusive. Many of the insights gained through the research process were provided by people who were of the majority in their respective cultures and communities, those most likely to already be part of the systems of power. As such, this report is unable to truly reflect the experiences of those who live and work outside or on the outskirts of systems of power, especially those who have been excluded due to inequity in the workplace.

It is vital to avoid developing a skewed narrative by focusing only on the loudest voices, or by missing the input of marginalized people who do not work in an environment in which they are able to disclose their stories. Initiatives to counter this skew include increased access to the conversation, creating safe environments in which conversations can take place, and the use of new and existing technology to provide voices to those previously excluded from dialogues.

Some people are unable to disclose their stories due to a lack of anonymity, a lack of direct communication channels with leadership, personal struggles with verbal confrontation, or a lack of support groups. Digital platforms for inter-organizational communication can provide alternatives to all the above, allowing people to make their voices heard. This applies equally to customer conversations. For example, one organization who contributed to the research project built a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) platform designed to support sight-impaired customers. 25% of that organization's sales staff are also vision-impaired, and the new system allowed for increased communication both internally and between sales staff and customers. The result was net benefits for staff, consumers, and the organization.

This emphasises how necessary it is for diverse groups to be involved in organizational decision making, with maximum input from the team members directly affected by those same decisions and in an environment in which disclosure is safe and encouraged. Leadership should encourage inclusion in agile teams based on factors beyond levels of certification: for example, diversity of work environments, cultural backgrounds, experience in alternative industries, experience with diverse customer bases, and so on.

It is also important to step away from notions of comfortable discussions. Keeping conversations non-confrontational is only of benefit to those inside systems of power. The promotion of dissent, the fostering of open dialogue, and leadership-driven initiatives to disrupt cultures of silence, are important.

By creating the conditions for respectful (if uncomfortable) conversations, and promoting diversity of thought, organizations can explore difficult topics and gather potential solutions. This helps create environments where employees feel that their entire selves - including their histories, opinions and marginalizations - are welcome in the workplace, as opposed to being valued purely for their most profitable skill sets.

Finally, we must recognize that some people are unable to contribute to these conversations, no matter how welcoming the environment. This may be due to personal issues (introversion, language processing disorders, etc.), or because of a perceived lack of safety, perhaps based on previous experiences. As such, it is vital for organizations to not require employees to contribute to conversations.

“Our company encourages learning, failure, and the ability to change direction. It draws in people from all over and we try to create a team that has diverse backgrounds and an inclusive mindset. So, in terms of business outcomes, that means that the people that are working on the problems [can] bring their diverse opinions."

For long-term practitioners, both agile and DE&I may become their own belief systems: the answer to all organizational and productivity related problems, and the lens through which all solutions are considered. In essence, they can become a pair of blinkers.

If not critically re-examined and challenged, these beliefs may create or reinforce barriers to diverse demographics and continue to impact on businesses and customers.

These beliefs include:

Belief #1: A diverse team gets better results than a non-diverse team.

Greater diversity does not automatically create more collaborative and productive teams. Differing viewpoints, operational structures, cultural norms and so on all create additional complexity and complicate the operation of teams and organizations. In truth, less diverse teams generally perform better than diverse ones, for a variety of reasons: easier alignment, reduced potential for microaggressions and tensions, etc. The obstacles created by increased diversity grow along with organizational scale and distribution.

Other examples of obstacles created by diversity include:

"We're aware that there are people that have loud voices in the room and quiet voices in the room, so we try and build and design our workshops to be quiet at times and to allow the people that may not have the strongest voice or not comfortable to speak up at those points and times, to be able to participate and add notes.”

Despite these obstacles, diversity in teams is both an inevitable result of working in a global market and provides more overall positive outcomes than the difficulties created along the way. Put simply, for businesses to thrive, they must embrace and plan for diverse teams.

However, diversity must be implemented deliberately, alongside well-designed policies for improving inclusivity and equity. Teams and individuals must be provided the tools, methods, expertise, and professional assistance required to truly engage with their differences and extract the benefits of diverse skill sets, mindsets, and lived experiences. Working thoughtfully to enable inclusion and equity will allow diverse teams to leverage their unique perspectives and out-perform non-diverse teams.

Belief #2: Agile is more inclusive and equitable than what came before it.

While agile is a highly effective approach to team and organizational management, the assumption that agile is an inherently better system of work - and in turn, that it is more inclusive and equitable than the systems that preceded it - is false. The concept of any system of work being universally ‘more equitable and inclusive’ is near-impossible to measure. What is ‘better?’ If the majority of people inside a system feel their new environment is more equitable, but a minority feel the new structures are a change for the worse, do the majority rule? Can any organization claim to be inclusive if they value one voice over another?

“People with disabilities or language differences may feel intimidated by agile.”

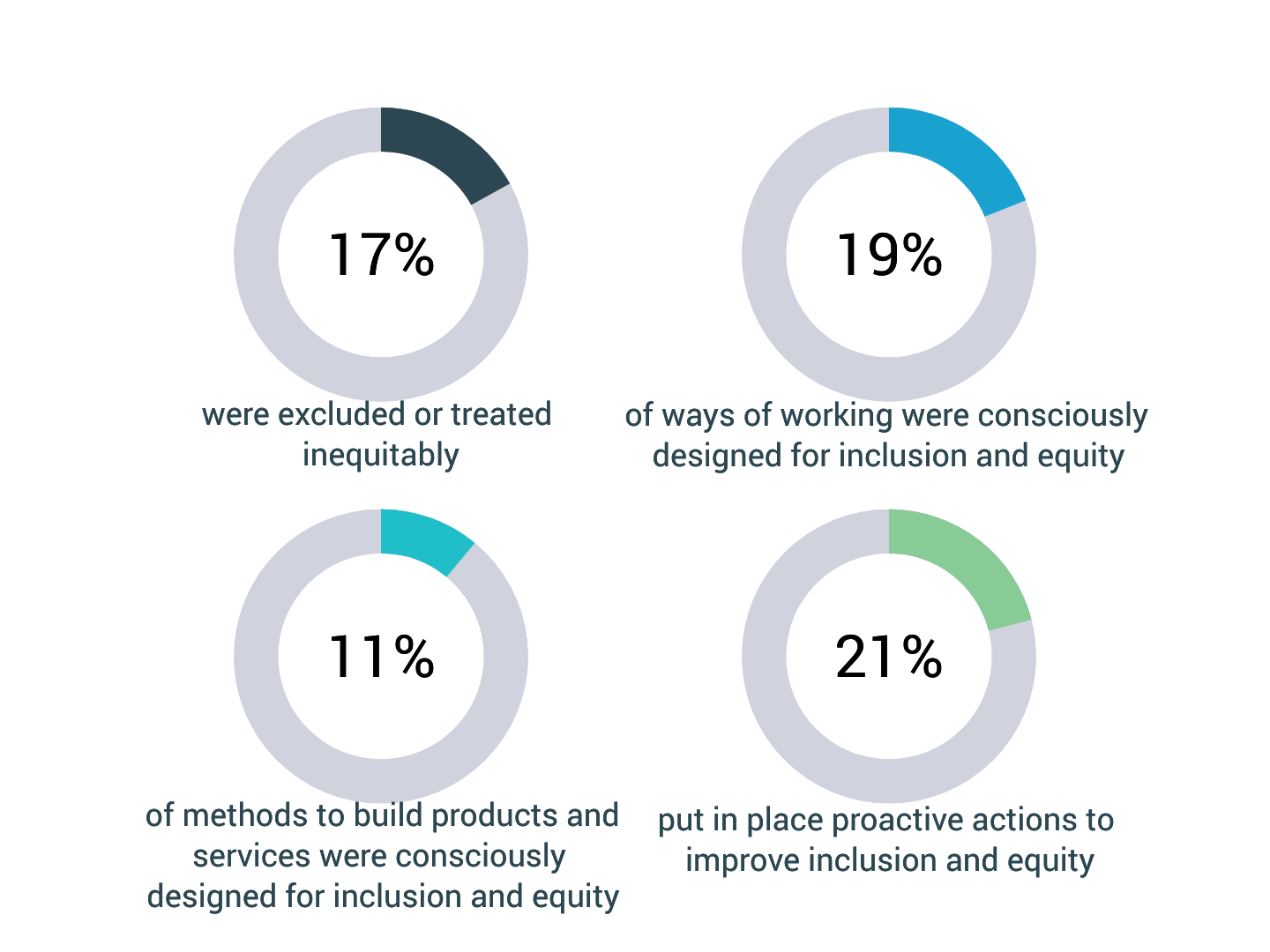

17% of respondents reported directly witnessing exclusion and inequity inside agile organizations. A further 26% believed that agile itself could actively create exclusion and inequity. As such, the most we can say is that agile holds the potential for improving inclusivity and equity but must be deliberately targeted.

Belief #3: Focusing on one or two areas of diversity first is a good start.

Some DE&I approaches take a staggered, piecemeal approach by first focusing on a few key areas of diversity, and then expanding understandings of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion outward once the initial changes to policy have been successfully integrated. Survey respondents indicated that this method was ineffective and actively harmful to DE&I. When diversity policies focused on specific groups, it created resentment, exclusion and inequity among those groups who had been left out.

This backlash against piecemeal DE&I underscores the fact that individuals often consider themselves diverse and/or marginalized across multiple dimensions: gender, race, sexuality, disability, education, and so on. Unless all these dimensions are addressed, some team members will always be excluded.

"Our organization truly believes they can have a role in creating equitable space. Background never matters – aptitude and attitude matter. They have specific programs for women to get back to work [after] taking a few months to 8 years. [Normally] it’s very hard to get back into tech."

One common pitfall that can exacerbate discrimination is to base DE&I approaches around the needs of dominant subgroups. For example, in countries where the majority population is white, workplace programs focusing on the needs of women in the workplace often take their cues from the needs of white women, while women of colour can feel increasingly sidelined.

Belief #4: I know how to work well with people.

Many agile systems and methods are structured around open communication methods which are (incorrectly) perceived to be equitable and inclusive. It follows that experienced agile practitioners may feel that they already have the skills to work productively with diverse groups.

“Agile is very "on the spot" and "who can talk". People who need time to process information before they can provide inputs are often overlooked. Same goes for people who may be suffering from social engagement issues. They are often forced to go with the flow and end up being overburdened or overlooked. It impacts job satisfaction, performance reviews and sometimes employability.”

In truth, the research shows that many people who assume they work well with others have only spent time working well with people who share their core traits - race, gender, age, and so on - and assume this collegiality is an innate character trait rather than a result of a homogeneous working environment. Alternatively, some people believe they work well with others because those around them are hiding their discomfort.

Belief #5: We can teach everyone to be inclusive and equitable.

While it is possible for everyone to improve their level of understanding regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion, the notion that everyone can become completely inclusive and equitable through time and training is false. Put simply, the breadth and depth of knowledge required to understand networks of intersectional diversity are beyond most individuals, even those who have dedicated their careers to the study of inclusivity and equity.

One of the core tenets of ‘understanding’ diversity is to accept that every individual’s experiences and needs are unique. It follows that it is likely not possible for any one individual to truly and completely understand the needs of another, let alone understand and act upon the needs of diverse populations.

"I have worked when people are forced to go through diversity training and stuff that they don't see the value in. They build up resentment around that and they don't want to be doing those things."

As many current DE&I approaches depend upon this flawed premise, we must instead look to creating a system built upon new ways of thinking, where inclusivity and equity are created and upheld without relying on the knowledge and understanding of individual team members.

Belief #6: We are on the right path to improving inclusion and equity for all.

The common assumption that current DE&I approaches are effective in the workplace is not supported by survey responses.

Some respondents observed that their organizations were disingenuous when they claimed to care about DE&I. Their programs were considered tokenistic or designed to appease, without any genuine belief in the importance of diversity and equity, or the benefits it could bring to the organization and customers.

Other respondents felt that forced DE&I programs had sparked resentment amongst employees who felt the programs had no value or were taking away from productive time. These employees were among both marginalized and majority / dominant groups.

"There are companies that have been obliged to use quotas, they also enjoy tax incentives. It's part of their CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) or SDG (UN’s Sustainable Development Goals). Companies are not thinking about using Scrum to be more respectful. They adopt a Scrum methodology to reduce the time to market.”

This could be caused by DE&I programs lacking sincerity, a lack of consultation with those diverse groups in need of equity and inclusion initiatives, and a lack of buy-in from leadership. Regardless of cause, interview and survey responses indicated that current inclusion and equity approaches are not working as advertised, that belief in DE&I does not translate into action, and that this is causing stagnation - or, in some cases, a reversal - in inclusivity and equity in some organizations.

Belief #7: We will adapt to someone’s needs if they ask.

Many organizations, teams and leaders believe that they will rise to meet the needs of their diverse community, so long as they are asked.

Individuals within those organizations also often believe that their needs will be met by leadership, so long as they are willing to disclose their marginalizations. This places the burden of change upon the marginalized person while lifting responsibility from the shoulders of leadership.

Respondents indicated that not everyone is able to disclose their needs, no matter how safe the working environment. By relying on disclosure as the first step in the process, these organizations had already erected barriers to inclusion and equity.

"It means you can think about things out of the box and try. I used to work on payroll, so rather than having just a binary way of selecting gender, we thought about it and added nonbinary and ‘I would prefer not to specify’ options… So that means that it's much more inclusive for everyone."

When people or organizations offer assistance only if asked, they are unconsciously drawing a boundary of ‘reasonableness’ around themselves by creating a standard of what is and is not a reasonable request, based upon preconceptions of the ‘default’ employee. These standards may be stated outright or implied through conversation, policy, or previous action (or lack thereof).

Employees with diverse needs may not feel comfortable asking for assistance, and once they do disclose, even the most supportive organizations will impose limits upon what they feel is appropriate.

This creates a barrier to attracting talent and discourages employees from applying for teams and organizations that are not already proactively and publicly working to address the needs of diverse people such as theirs.

Belief #8: Our leaders and product experts are making the correct decisions to support the needs of diverse populations.

Strong, invested leadership is vital in the creation of diverse, inclusive, and equitable environments. Most organizations rely upon these leaders and product experts to have the necessary knowledge and experience to make thoughtful, sensitive, informed decisions regarding the needs of diverse teams, workforces, and customers.

The assumption is often made that, because a leader has experience working with diverse communities or DE&I training, they will understand the needs of those communities. Likewise, it is a common assumption that product owners and agile teams (who also have likely undergone a degree of DE&I training) have ongoing relationships with their customers and understand their needs.

“It can be a tension between doing things for those communities [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] but not having active representation on staff and people from those backgrounds.”

However, as previously discussed, diversity dimensions are so broad that it isn’t possible for a single person to have the necessary context and understanding to make decisions of that depth. The potential exists for a leader to consult with a diverse mix of team members and customers to make more considered decisions, but the same potential for bias remains if the communities they are consulting are not truly diverse, or if the consultation methods are not suitable for the community in question.

For example, a leader may act proactively and consult with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and LGBTQI+ members of their community before beginning product development, but neglect to consult with disabled or neurodivergent team members. Alternatively, leadership might consult with a diverse group of team members and customers, but not create the necessary atmosphere of safety and inclusion that would allow those people to speak honestly about their concerns.

Finally, no matter how safe the environment, if leadership waits for diverse groups to speak about their concerns, then they will always be one step behind, and placing the burden of responsibility upon marginalized groups. Leadership must be proactive and design equitable and inclusive ways of working without requiring diverse groups to expose or discuss their struggles.

The customer is the heart of an agile organization.

The ultimate purpose of agile values and ways of working is to deliver better, and more relevant, products and services to customers, quickly and efficiently. As such, understanding the diverse needs of customers is at the core of successful agile organizations.

Organizations that don’t take this into account risk dedicating resources to the development of products and services for only a limited subset of customers.

“Physical barriers can remain even when accessibility may have been considered – e.g., wheelchair users who can’t see the exhibits at the zoo because of the height of handrails.”

Creating a product based on a manager’s assumption of customer needs may have worked in times of reduced competition, but the speed of market developments and the overnight appearance of competitors means that customers are spoiled for choice and will gravitate towards products and services that satisfy their specific needs.

Instead, organizations can use agile ways of working in conjunction with DE&I practices to better engage with their customers, understand their unique perspectives, work with them through iterative development cycles to ensure their products are truly meeting their current and future needs, and improve overall business outcomes as a result. Understanding diverse customer bases via DE&I is a vital component of this success.

Making Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion a vital part of an organization’s operations directly benefits the customer. A workforce that doesn’t reflect the diversity of their customers is at risk of not understanding those customers. Whereas a diverse and empowered workforce can better communicate with and understand their customer’s needs, match products with demographics, create more innovative solutions, and increase an organization’s overall representation in the community it serves.

This can be enhanced by matching the lived experiences of the product team with those of potential customers, helping team members find better solutions to the problems their customers face. A diverse workforce is also better able to communicate and create bonds with their customers.

A diverse workforce will have greater investment in products and services developed for their demographics, resulting in better overall projects and increased business outcomes. Diverse teams have greater credibility among clients and will be better positioned to explore new market opportunities in diverse communities. In short, inclusion is a fundamental aspect of creating more successful products.

“Embracing diversity and inclusion [is] why we are so successful and why we've seen year-on-year net promoter score (NPS) improvements from customers. [It’s] also why we've been such a successful and profitable business.”

Many products are not suitable for specific groups: for example, sight-impaired people may struggle to use products with complex fonts or small screens, as they were not consciously designed with accessibility in mind. In addition, a lack of diverse perspectives may lead to homogenous approaches to solving customer problems, or well-intentioned but flawed attempts to impose (for example) an able-bodied person’s understanding of disability onto a disabled person’s lived experiences.

Common agile methods reinforce this. The drive to quickly build and market a product, learn from feedback, and iterate upon that initial product, can lead to a rushed release that is ignorant of a diverse market’s key needs. In addition, an iterative method will not eventually lead to a good product for diverse customers if their needs were not considered and designed for in the early stages of the product life cycle.

On the other hand, diverse teams working in more inclusive and equitable environments will have a better understanding of those key needs, allowing them to extend into new markets, build respectful relationships with customers, create greater opportunities for innovation, and reduce groupthink.

Organizations cannot afford to ignore these key markets; for example, 20% of Australians identify as having one or more disabilities. Their needs might be overlooked if organizations do not integrate DE&I into their fundamental practices.

Many organizations encounter difficulties when trying to create equitable and inclusive working environments. The first question to ask in these situations is, who are the customers of “agile” or business agility itself? Who does an agile approach serve: internal customers, external customers, staff, partners, or shareholders?

In the context of a transformation, ‘customers’ are anyone impacted by agile ways of working.

As discussed earlier, ongoing customer feedback and input during the development cycle is one of the key differentiators between effective agile products and services and non-agile products. This is also true of organizational transformations.

To improve agile (or business agility) ways of working and enable a better working environment, they must be developed in constant consultation with team members, leaders, staff, consumers, and more. Understanding these customers (which requires expanding consultation beyond the immediate circle of current employees) and learning how agile ways of working affect their lives, is a primary step in becoming more effective.

Agile ways of working are sometimes implemented in response to problems or roadblocks inside organizations instead of being designed in direct response to the needs of customers, and without customer consideration and consultation. The consequence is exclusion and inequity.

This does not imply exclusion or inequity for all, but rather that exclusion is a genuine risk if transformations or ongoing ways of working are reactive only to the needs of the majority, or don’t consider the existing and aspirational cultures of the team.

These transformations can create additional roadblocks in an already complex time of change and reduce overall business outcomes. Staff grow frustrated when a well-intentioned transformation makes their situations more difficult due to a lack of consideration and consultation, leading to inappropriate or ineffective ways of working.

This effect is compounded when no tools have been put in place to measure the scope or success of the process, or when tools measure certain success metrics while overlooking the ways in which the process has impacted DE&I. This lack of alignment between what organizations, teams and customers want, compounded by a lack of defined internal culture and explicit cultural transformation, turns agile ways of working into an imposition upon those who should benefit most.

These missteps may be due to a fundamental lack of understanding regarding DE&I. Respondents repeatedly noted that there was no consensus regarding the standards of what was inclusive and equitable, so it follows that mistakes may be made when important decisions regarding DE&I are left to teams without the necessary skill sets or supporting frameworks. This is compounded when coaches without expertise in DE&I - both knowledge and applied experience - inadvertently coach teams in methods of work that reinforce systems of exclusion and inequity.

Part of the solution is to take the expectations and burden of DE&I off the shoulders of regular employees and embed DE&I specialists inside organizations to assist in the development of inclusive and equitable ways of working.

In addition, input should be sought from diverse customers both inside and outside the transformation process, and teams should be asked to discuss and expand their understanding of diversity. This will assist in reducing instances of exclusion and inequity from the beginning and help tailor agile ways of working for the needs of their diverse customers.

“If you don’t have agile mindset, it doesn’t matter how many agile practices you employ you should not consider yourself to be agile.”

The agile mindset is a set of attitudes, beliefs, and habits that support working in an agile or business agility environment. Key to the creation of an agile mindset are concepts like pride in the work, collaboration, transparency, respect, honesty, and open communication. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, however, are not commonly included as keystones in agile mindsets, or given sufficient weight when creating new ways of working.

Evidence suggests that some people struggle with the shift to an agile mindset, despite agile and business agility being centered around the empowerment of individuals. This may, in some instances, be due to agile as a brand losing credibility in business contexts; agile is often touted as a catch-all solution to organizational conflicts caused by structure and hierarchy.

The result is that leadership are deploying agile as a band-aid solution without examining the root causes of problems and asking team members to use agile ways of working without understanding why those methods are effective or how those processes relate to their current problems and mindsets.

The result: burnout. This is compounded by change fatigue, where leadership implement endless quick-fix solutions without proper knowledge or coaching.

People in these situations may find it difficult to feel at home inside agile systems of work, even if those systems are functioning properly. Moving from a strictly managed hierarchical working model to an autonomous, spontaneous, ideated business agility approach can be difficult. Likewise, becoming part of an autonomous team without shared knowledge and experiences can be alienating.

Even with agile coaches on hand to assist, adapting to an agile culture and mindset isn’t simple for many individuals. It requires employees to unlearn traditional ways of working drilled into them over decades: hierarchical decision-making, responsibility being passed up and down chains of command, etc.

Respondents noted that a common cause of these issues was that people often struggle to adapt when entering areas or organizations that don’t immediately fit their expectations and beliefs. This can refer to individual differences - cultural, mindset, ways of working, and so on - or differences between teams and working communities, where methodologies and systems of communication clash.

Trust and psychological safety are interlinked concepts, especially as they pertain to the workplace.

Trust refers to the confidence one person has in another; for example, an individual believing that a sensitive report submitted to their direct superior will be acted upon responsibly.

Psychological safety broadly refers to an individual feeling that their mental and emotional wellbeing is valued and protected: for example, knowing that they would not be punished or humiliated by the collective for raising questions or challenging authority.

While both may seem similar, trust refers to how individuals see and relate to other individuals, while psychological safety is generally defined by how members of a group are treated by others in that collective.

Comfort, like trust and psychological safety, is an individual feeling that’s difficult to measure. Comfort derives from the trust and psychological safety provided by individuals and collectives.

People are the heart of agile, and personal experimentation and growth is the core of becoming a more capable agile professional. As such, agile offers unique opportunities regarding the building of trust, comfort and psychological safety that may not exist in more traditional organizations. For example, the Daily Stand-Up is a tool encouraging team members to communicate openly and honestly about their progress, blockers, and what they need from their teams.

Tools like the Stand-Up help build an environment of psychological safety and comfort, so the team can function effectively.

Many agile organizations also have an approach towards new team members that asks them to utilize the skills they already have while developing themselves in new areas, all to better assist their teams and build better products. This creates opportunities for them to learn, grow and develop in a supportive environment, with the expectation that their skills will evolve over time.

“I am the first-generation immigrant from [Asia], a female working mother, a single mother. It was challenging to start my agile career, but [the USA company] gave me an amazing opportunity to be a Scrum Master, a [servant] leader and also, you know, a person. But by working this agile way and knowing how important it is to keep learning and to be humble and to serve others gave me such a great satisfaction personally and professionally.”

However, while agile may offer opportunities for people to use their personal circumstances as part of their individual strengths, not every agile environment is equally welcoming, or is positioned to offer every team member trust, comfort and psychological safety. Not every new employee will feel comfortable disclosing their histories and circumstances, especially if the society outside that agile environment is actively hostile towards their marginalizations.

This creates a paradox: successful agile ways of working rely upon psychological safety, which in turn depends upon disclosure, which isn’t viable, inclusive, or equitable for everyone. For a team to work at their best under current agile frameworks, some team members must risk exclusion and inequity.

In short, agile is a tool that can create equitable and inclusive conditions but is not an automatic answer to the question of how to create or enhance supportive working environments. There needs to be a system which is supportive of disclosure but does not require disclosure for an individual to succeed.

So, if agile is built around principles of individuality, inclusion, empowerment, and collaboration, why do some agile workplaces fail to create environments of trust, comfort and psychological safety? Respondents indicated that many agile organizations were lacking in key areas crucial to making team members feel safe and included. Some of these factors are tied to the lack of DE&I values in the organization's mission and operations, while others are symptoms of larger cultural prejudices.

For example, respondents indicated that, in societies where certain biases are generally accepted or even encouraged (including racism, homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia, etc.) those same biases pervade agile organizations regardless of whether there is a leadership team working actively to combat them. This can occur even in communities where laws exist to combat those prejudices.

Many respondents stated that, whether overt or subtle, racism persisted inside their organizations as a result of cultural and legal statutes and was ingrained into ways of thinking. These instances of racism manifested in the form of pay inequality, missed promotions, and microaggressions. Respondents also indicated that these biases could be generational, and as such were difficult to overcome through targeted training or policy.

The result was that many respondents didn’t feel a sense of trust and belonging in the workplace, and struggled to perform at their best, leading to poorer outcomes for teams and products.

To begin overcoming these biases, the pursuit of trust, comfort, and psychological safety must be baked into an organization’s values. Leaders must create a psychologically safe workspace and demonstrate a commitment to equity. Finally, conditions must be continually monitored for discrimination and bias.

Respondents noted a gap between organizations that walk the walk, and those who only talk the talk. Many organizations pay lip service to DE&I as a core of their culture by enshrining respect, understanding, honesty and mutual collaboration into their values, but don’t translate those same values into concrete action.

For example, respondents discussed facing challenges when trying to champion inclusive and diverse programs for people of different ethnicities, such as Indigenous and First Nations people. While the need for such programs is generally acknowledged, it was often difficult to gain material support or organizational resources for such programs.

Agile is meant to be a culture of inclusion, but little explicit design or effort has gone into turning intention into action. Situations where organizations espouse equity and inclusion but fail to create proactive action or follow up on disclosures of bias are disheartening, damaging to morale, and may lead to team members exiting organizations in favor of those who explicitly uphold their values. The final result: weakened teams, damaged reputations, and substandard business outcomes.

"My organisation doesn’t discriminate on any criteria (gender, religion, caste etc.). During my training, one person changed gender from male to female. We interviewed the person. She was brilliant with her ideas. She is doing a wonderful job in her project. I have seen 3-4 cases like this."

When discussing the successes and failures of agile organizations in creating diverse, inclusive, and equitable working environments, it’s important to note that there is no single agile approach. Every agile organization or community takes inspiration from the agile principles and values and may use common agile tools and processes in their day-to-day operations, but the ways in which these principles, values, tools and processes are implemented is highly individual.

The same can be said of the ways in which agile environments work to create inclusive and equitable working conditions. The shapes organizations eventually take are often guided by industry and professional bodies, agile training organizations, leaders and coaches, team members (both with and without agile knowledge), and studies of previous transformations.

These influences have the potential to provide foundations and guidance for the creation of inclusive and equitable agile environments, and to drive significant change in the field of a unified agile & DE&I. Respondents indicated that they wanted those influential bodies to place a greater focus on DE&I, and to be proactive in driving change. However, evidence gathered from those being excluded and treated inequitably in those same environments suggest that current efforts by these influential bodies have not yet been successful.

There are two primary types of industry bodies who assist and influence agile organizations: agile professional bodies (for example, the Business Agility Institute, Scrum Alliance, and the Program Management Institute), and HR/DE&I bodies.

Each of these bodies help define and promote frameworks, best practice, research, and certifications. Each of which is aimed at improving the working conditions inside the industries they serve, as well as empowering and uplifting individuals inside those industries. As such, these bodies can be considered the owners or custodians of the unique approaches they have developed. This ownership grants them a measure of influence in their fields and it is important to consider the collective power that these organizations have when discussing agile and DE&I.

These approaches are often designed by long-term industry professionals, who are established and hold a measure of power. As a result, many of these approaches have not been explicitly designed with diversity, equity, and inclusion in mind, or with the input of diverse and marginalized people. While DE&I is often implied, it is less common for it to be called out explicitly as a required symbiotic component, and thus inadequately catered for in terms of agile values, principles, tools, and systems.

The ultimate result: implied DE&I doesn’t lead to action. Without a unified movement across these industry bodies towards enshrining inclusion and equity within their values and working models, it will be difficult to make inclusion and equity a reality within agile organizations, and thus allow agile to truly excel.

It is impossible to make sweeping generalizations about the lack of DE&I in agile organizations, when those organizations take so many forms, with so many individual objectives. Most agile organizations are purely consumers of agile, using new ways of working in the pursuit of better business outcomes.

Some organizations seek to help others perform agile transformations on a large scale, while others aim to solve very specific problems or train individuals in targeted ways that may not intuitively overlap with the pursuit of DE&I.

The ‘flavor’ of agile each organization pursues will be based around their core objectives. So, if a decision is made to initiate a transformation in a pilot team, the ‘flavor’ of agile chosen – and in turn, the industry bodies, coaches, and certifications selected to support that transformation – will reflect the organization's overall mission.

When organizations who center their culture around DE&I engage in transformations, leadership will generally seek coaching and support from organizations which value equity and inclusion. As discussed, for any model of agile to succeed in delivering business outcomes, it must intrinsically address DE&I.

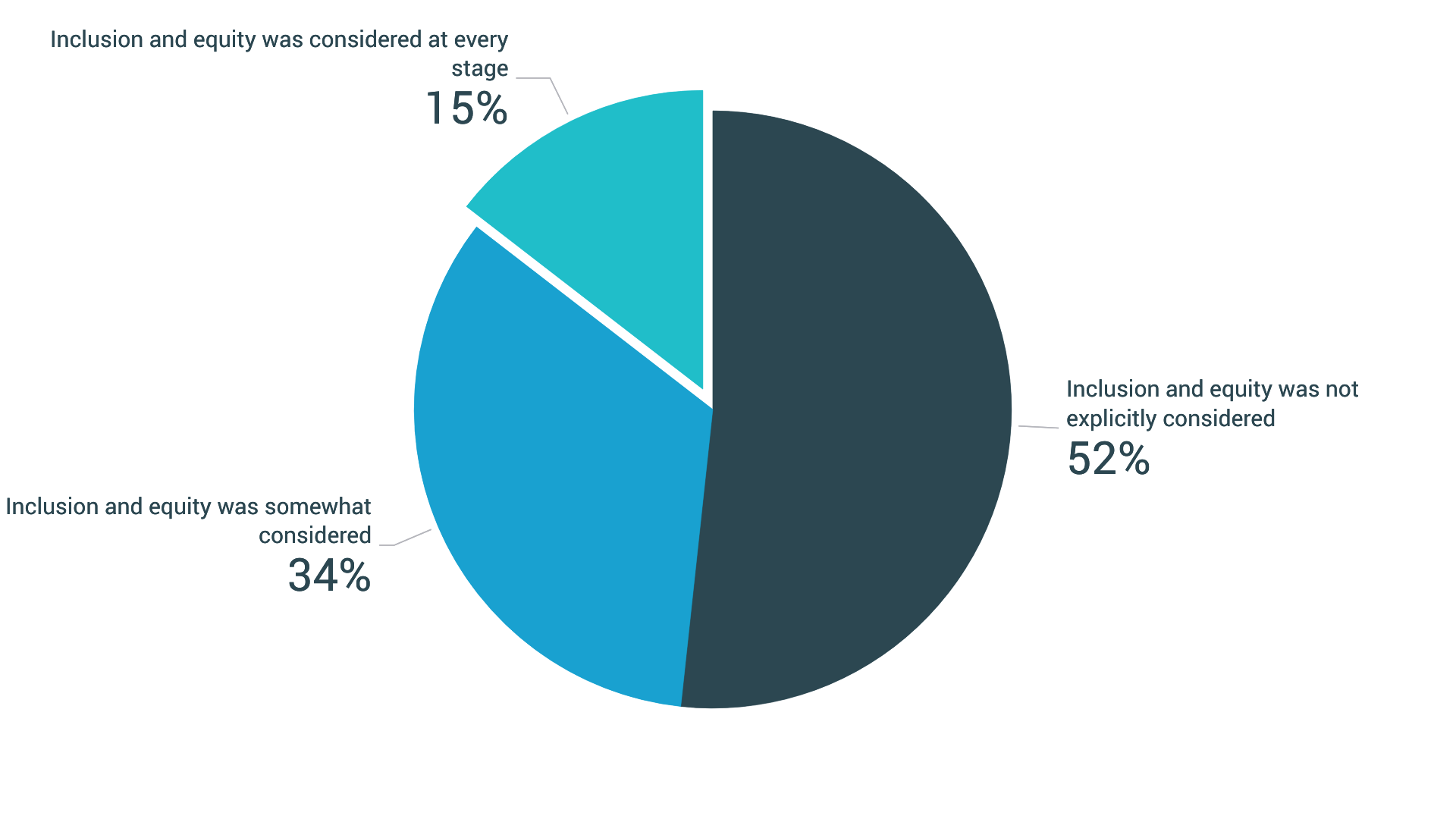

A recurring trend among respondents was that, regardless of organizational manifestos, their employers did not place enough emphasis on either sustainable agility or building an environment of equity and inclusion. As mentioned earlier, agile transformations are sometimes used to solve specific problems rather than creating an overall agile mindset. As a result, some agile transformations and practices are not often seen as opportunities for improving inclusion and equity, despite those concepts working hand in hand with agile.

No single body bears responsibility for this: respondents indicated that leadership (who often don’t specifically set out to transform their internal culture), coaches and industry bodies (who may not be guiding the community towards DE&I as a specific focus) and individuals (who do not actively interrogate acts of exclusion and inequity in their teams) are just not taking the time before, during, and after agile transformations to consider equity and inclusion – despite it being critical in order for business agility to reach its full potential.

Transformations face several other challenges. For example, teams shifting to agile ways of working can experience confusion when it comes to understanding value streams and ownership of work/accountabilities, often because they haven’t been given a solid understanding of why the transformation is taking place. Respondents struggling to understand agile transformations in their workplaces reported a general attitude of,

“We’re doing it because most organizations are doing it.”

As opposed to a transformation in pursuit of empowerment, enablement, improvements to flexibility, autonomy, resilience, and so on. The same can be said of organizations pursuing improved DE&I.

There’s often an element of desperation in these context-less transformations. Organizations experiencing difficulties may look to their successful partners and/or competitors for answers. For example, by copying the Spotify model without understanding why that model is effective for Spotify’s specific situation. Or without being aware of that model’s failings and understanding the process of mistakes, experimentation and ideation undertaken to develop it.

With no consensus as to why a transformation is taking place, or what benefits it will offer an organization, it is difficult for employees to be invested in the transition or to believe in the promised outcomes.

"I think that inclusion and equity in the agile way of working can bring a lot of value. I feel that my organization is making an effort to incorporate it into our corporate values. As we are starting our journey to becoming Agile, it becomes even more clear that inclusion and equity should play an instrumental role."

Put simply, the why and what of transformation are critical to get right, before pursuing the “how”. Without purpose, agile is often mistakenly reduced to a series of tools and methods. A shared purpose is an engine that unifies teams, clarifies goals, and gives context to methods. It also allows team members to choose at the beginning of a journey whether to sign on or not, rather than feeling obligated to take part in a system that doesn’t suit their goals or ethos.

This obligation also creates resistance to change, as observed by respondents. When a shift to agile ways of working takes place, it’s not unusual for older or more experienced staff - who have developed effective ways of working inside a traditional structure - to feel like the changes are targeted towards younger staff. This may be because mindset shifts are more difficult for staff with longer tenures.

This contributes to the “frozen middle,” where senior staff and middle management - who would ideally be enthusiastic agents of change - are not given the necessary support to understand or embrace it and can end up working against positive transformations. Additionally, coaches and transformation leads may be affected by ageism and focus their attention on the employees they believe are most capable of change.

To solve this, agile coaches must find new ways to assist workers struggling with drastic shifts in mindset, and to demonstrate greater empathy and patience with any team members experiencing feelings of insecurity. Organizations, teams, and leaders must also ask why they are undergoing a transformation, how business agility will help their existing systems, what long-term benefits agile can offer their teams beyond immediate band-aid solutions, and how business agility will enhance organizational values. This is especially true in the realm of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which agile needs to be successful.

“Leaders and team to have empathy and understand individual's needs.”

In the context of agile organizations, leadership doesn’t only refer only to upper levels of management or leaders as traditionally labeled in the hierarchy. It encompasses anyone in an agile environment who provides guidance and support to others.

To be a leader in any working environment requires vision for what the team and individuals can accomplish, both personally and professionally. It demands a higher level of understanding regarding the individual needs of team members, the challenges they face, obstacles both inside and outside the working environment, and what is required to overcome those obstacles. It also requires the willingness to act when others will not, to learn what it means to lead, and to confront systems of bias to empower their teams and colleagues.

As such, leaders are often expected to have a comprehensive knowledge of agile values, principles, tools, and processes, as well as an understanding of how Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion affects their colleagues and customers. Despite this, they are often perceived as not having a sufficient understanding of either agile or DE&I to truly act as leaders in their respective fields. Respondents also report hypocritical leaders – those who give directions and impetus but fail to lead by example, eroding the confidence of their teams and undermining transformations.

It may be that these leaders have not pursued a greater understanding of either agile or DE&I because they fail to see the immediate benefits for themselves, their teams, and their organizations. Some leaders find it more effective to learn a little about a lot - as such, they may simply never have the time or resources to become experts on DE&I.

In the same way, the untapped power of a more inclusive and equitable agile model – which can, like all transformations, be achieved steadily and incrementally – is often not recognized by leaders, agile professionals, or HR/DE&I staff alike. The importance of DE&I to the individual may be recognized, but not the potential material gains to agile business outcomes. It will remain difficult to spread this understanding unless industry and professional bodies encourage and create innovation in the intersectional space between DE&I and agile.

Leadership adoption and understanding of DE&I is also currently inadequate, according to respondents. While key leaders may have some understanding of what is required to improve equity and inclusivity, that understanding is not shared equally throughout many organizations. In addition, agreements about the changes that need to take place in the short and long term are lacking. The result of this is inaction and ineffective leadership.

"For [our] successful transformation, leaders [are] actively involved [so] they know what the teams are doing. There's a lot of transparency and continuous communication and involvement right from the top-level leadership."

In the case of ineffective leadership or the previously discussed ‘frozen middle’, leaders must be provided with a clear understanding of their new roles and responsibilities, the importance and value of the new roles, and how they facilitate agile ways of working. Leaders may struggle if not provided with sufficient internal and external support during any transition. Finally, bruised egos may also need soothing.

These steps are crucial, as leadership is necessary throughout agile organizations – not necessarily to manage people, but to support, nurture, drive attitudes and proper messaging, foster environments of collaboration and understanding, and to set behavioral standards and expectations regarding inclusivity and equity. Leaders with this level of responsibility must be pervasive throughout organizations, and it is often necessary to look beyond the ranks of traditional management.

Perhaps the most important responsibility of these leaders is to manage conflicts - both in terms of business operations and differences of understanding. It is for this reason that leaders must be numerous, distributed, and both drawn from and embedded within the teams they serve.

However, diverse leaders can’t take these steps alone. They must be supported from the top, with unity of purpose and unity of messaging. If executives are not invested in the process of cultural change, the leaders supporting that change will be left rudderless.

The first and most vital step in ensuring leaders have the support they need is to incorporate inclusivity and equity into the core values of an organization. Values may not initiate change, but they provide a foundation for senior, middle and team leadership, and allow leaders to take concrete steps towards translating those values into meaningful action.

Becoming a coach has historically been considered an opportunity for experienced employees in many organizations, which comes with an elevated level of authority, respect, and responsibility. But seniority or experience in a particular field doesn’t automatically translate into coaching expertise. As agile ways of working become more popular, it is becoming clear that employees and teams of all levels need expert coaching to thrive.

For this, they need coaches who not only understand their goals, skills, and ways of working, but who also have experience in human relations, teaching, equity, and inclusion. In other words, coaches drawn from the ranks of employees based upon previous performance or expertise in a specific field are often inadequate for the needs of modern agile teams.

A good coach is an expert in people first and foremost;

And yet, training and mandatory skill sets for coaches often do not emphasize an understanding of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion - the very study of how people can work better together. This gap between what a coach needs to succeed and what they’re provided is an ongoing cause of conflict within agile organizations.

By contrast, coaches with DE&I experience present organizations with new opportunities. They can be placed throughout teams to act as constant mentors and guides, helping teams work in inclusive and equitable ways from day to day while also optimizing team and business outcomes. This removes the need for every team member to have a comprehensive understanding of DE&I and ensures that the organization's values are being communicated clearly and evenly throughout its teams and divisions.

Business agility generally takes control away from middle management in favor of placing decision-making powers in the hands of the people most often impacted by them: team members. Processes, too, are given to team members, to choose the tools they need to get the job done.

To manage these added responsibilities, teams must;

They must also be aware of how their decisions affect those outside their teams and organizations. This includes customers and potential future team members, all of whom interact with agile teams in different ways. Teams which do not consider how they are perceived and how their policies and behaviours affect outsiders will lose customers and repel diverse talent, thus missing out on future opportunities.

Other factors impacting employees (some of which can be solved through better coaching, and others which may require more systemic transformations) are more visible to outsiders than others. For example, when discussing inequity or bias in the workplace, many people think first of breaches of basic codes of conduct, such as misogynistic and predatory behaviour, overt discrimination against LGBTQI+ employees, racial microaggressions faced by BIPOC, etc. However, there are many non-inclusive and inequitable factors that are hidden to all except the person being directly impacted.

Some of these problems and incidences, as reported by interview and survey respondents, included:

These issues and incidents, while having a real impact upon respondents, are often not being considered as acts of exclusion or inequity. Accessibility for disabled and neurodiverse employees, in particular those with invisible disabilities, is not brought to the forefront of conversations regarding inclusion and equity in the workplace, and those who struggle often do not feel empowered to discuss their difficulties. As a result, the necessary changes to the working environment - which are often small and simple to implement - slip beneath the radar, and the true value of those employees is reduced.

The larger effect of these ongoing inequities is that employees with disabilities, marginalizations, or other diverse attributes and needs, will soon feel as if their whole selves are not wanted in the workplace. These employees may not disclose their needs, or discuss instances of bias or marginalization, as a pattern has been established in which their concerns are not taken seriously. Transformations and agile ways of working should enable people to be more present and transparent regarding themselves, their needs, and their goals, but those same systems can serve to push people away.