July 29, 2020

Author: Jardena London

Key Contributors: Sally Parker, Nadezhda Belousova and Laurie Reuben

Editor: Chris Hayes-Kossman

What is Structural Agility?

How can Structure help your business achieve true Agility, and survive the challenges posed by the changing environment?

The goal of Business Agility is to adapt and respond to the pressures of a changing environment, but no business can function without a structure that guides decision making, governance practices, and working methods. So what is Structural Agility, and what role does Structure play in an organization’s journey towards creating an agile environment?

“Structure enables flow”

Structural Agility rests on the core concept that Structure enables flow; specifically, the flow of information, energy, and resources inside an organization. Understanding how Structural Agility enables flow begins with three key terms: structure, boundaries, and rules.

Structure is anything that creates boundaries and rules to organize people and activity towards a shared purpose. Structure in the context of business includes policies, governance practices, team structures and reporting relationships that help people align and fulfill their goals.

Boundaries are the borders where things start and end, and help the human mind see complexity more clearly. Organizational structures start by bounding work and putting bounds around people. Bounding work gives us ways to package and monitor our work. Initiatives, programs, projects, products, user stories and tasks are all examples of bounded work. We create people boundaries with structures like job descriptions, org charts, project/product teams and communities of practice.

Rules are a set of formal and informal directives that support the boundaries. Formal rules are expressed through policy, governance framework, process, etc. Informal rules show up primarily through culture. It’s not uncommon to see an organization attempt to remove a boundary, only to find that the informal rules have become the boundary itself. One common example: in organizations where formal approval rules are removed, people continue to seek approval before moving forward with major projects or decisions.

Examples of formal rules for projects include: must have a project manager assigned, must have metrics, must have weekly status report, must have a due date, must be in the project management system. Informal rules sometimes exist in contradiction to formal rules. For example, the informal rule might be that a good project manager knows how to circumvent the formal rules to meet the due date.

When these three elements are combined in the context of Business Agility, we find Structural Agility: a framework where the boundaries are more permeable than a traditional structure and the rules are few and simple. We express the definition and principle of Structural Agility in sand rather than stone, because, like Structural Agility, the principles themselves are both permeable and emergent. This is the working definition today:

STRUCTURAL AGILITY: THE CAPABILITY TO CONTINUALLY CREATE AND ADAPT STRUCTURES THAT GIVE LIFE, AND ENABLE THE FLOW OF VALUE, IN SYNC WITH AND IN RESPONSE TO THE ORGANIZATION’S CHANGING ENVIRONMENT.

What role does structure play?

Structure is necessary for the function of any organization. The greater the number of moving parts, the more likely any system is to collapse if its processes, rules and boundaries are not cohesive. Conversely, if those same rules and boundaries are too brittle, they can lead to disaster.

To use Robert Fritz’s [Robert Fritz, The Path of Least Resistance for Managers, 1999] analogy of a car’s alignment, a driver can be trained, incentivized, and convinced that “best practice” is to hold their steering wheel straight when driving on a straight road. But if a car is out of alignment, a driver will be forced to either ignore best practices, or hold the wheel straight and run off the road.

Structurally, there are two possible solutions: change the rules to let people adjust the steering as needed, or fix the alignment. Both are vital. In the long term, adjusting the steering steals energy away from effective driving of the car, so fixing the alignment is important. Since we can’t know exactly when a car will go out of alignment, we account for the unknown by letting people adjust steering as needed.

To extend the analogy, a car’s alignment supports the other systems in the car. The alignment is neither superior or inferior to the engine and the drivetrain. They all work in service to each other, and in service to the car’s overall purpose.

Structural Agility is a whole system approach. In organizations, structure is important, but it’s not the only thing making the system work. Structural Agility serves the other parts of Business Agility, and vice versa. This paper will conclude with an attempt to connect the dots between Structural Agility and the other Domains of Business Agility.

Structural Agility leverages structure for the purpose of enabling flow, rather than trying to control it. We use the language of living systems to express the idea that we are creating conditions for life, rather than directing and imposing activity. An example of this is moving from approval processes to prioritization criteria and WIP (Work in Progress) limits. In the past, approval processes were designed to manage capacity implicitly, through chain of command and form submission. These processes were, by design, intended to throttle output in line with capacity and resources, but there were no processes in place to resolve the constant conflict between capacity and priority. Agility processes make the prioritization criteria and capacity explicit, reducing the friction of flow and allowing a team to channel energy into the work instead of an extended, exhausting approval process.

At any point in time, organizations are perfectly designed for the outcomes they are getting [Based on W. Edwards Demming’s quote “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”]. Pushing harder won’t change the outcomes if the structure won’t support it. To return to the earlier car analogy, if a vehicle is designed for fuel economy, no amount of pressure on the gas pedal will turn it into a racecar.

Structural Agility is dependent on shared identity. Structures manifest around a shared identity. The structure is the embodiment of the organizational beliefs. Structures drive behaviors that further anchor and reinforce the understanding of the shared identity.

According to Margaret Wheatly, “Identity is the sense-making capacity of the organization”. [Margaret Wheatly, The Irresistible Future of Organizing, 1996.] If an organization lacks a cohesive identity, structure just becomes a set of rules. A shared identity sets the stage for the organization to adapt, and, as per Wheatly, for people to “use their shared sense of identity to organize their unique contributions.” It’s impossible for any organization to foresee all the ways it will need to adapt through its lifetime, and it’s imperative that organizations can intake information, make sense of it and apply it in ways that are not yet known.

The concept of “identity” connects with the Domains of Business Agility from the Business Agility Institute; specifically, the concept of the Organization as “One Team”. A shared, well understood identity is a key characteristic of an agile organization.

Why do we need Structural Agility in today’s world?

For companies looking to be more responsive and adaptive, it is vital to identify which existing structures enable flow, and which structures block flow. Every organization has a finite amount of energy created by their employees and team members, and an effective organization needs to optimize the energy that goes into the work, and reduce energy lost by compensating for or working around internal structures that block flow.

To return to an earlier metaphor, if a car’s steering is out of alignment, energy is consumed by constantly compensating for the misalignment. Eventually, that energy will run out. In a business sense, a useful question to ask is: “If your competitor launched a product today that threatens your market share, what would it take for you to mobilize a response?” (note: that’s mobilize, not even implement). A common answer sounds something like this: “We’d need a Powerpoint that makes the case for response, organize a meeting with the higher ups, and coordinate a date. If they agree, we’ll work on getting budget approval, then figure out what projects need to be deprioritized and who needs to be reallocated to get a team off the ground.” That’s all wasted energy, burned up while navigating internal processes. In Lean terms, this is “non value-added work.” In structure terms, the structure is not enabling flow. We see this entropy, or energy leakage, internally in organizations, but also externally in the ecosystem. Structural Agility is the ongoing journey to seek structures that allow for adaptability and flow.

What are the Principles of Structural Agility?

Structural Agility, by definition, can’t be rigidly defined. It has no concrete rules and will always adapt in response to changing business environments. However, it is possible to create a set of business principles that give Structural Agility a form. Like the definition of Structural Agility, these principles are also written in sand, rather than stone, with the expectation that they will evolve.

These nine principles of Structural Agility are based upon three existing disciplines: Living Systems, Systems Thinking, and Dynamic Tensions (Polarities).

Living Systems are open, self-organizing life forms that interact with their environment. These systems are maintained by flows of information, energy and matter . Structural Agility marks a shift in thinking of organizations as “machines that use humans as resources” to “living systems made of humans.” This change in form and paradigm, and the process of building and leading a living system, requires different skills and structures as compared to leading a machine. One of the fundamentals of Living Systems is that we can create conditions for the system to flourish, in contrast to a machine which we seek to control.

Systems Thinking considers the whole system, and how the parts of the system are interconnected, over multiple time horizons. As per Donella Meadows, “A system consists of three kinds of things: elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose.” [Meadows, Donella H.. Thinking in Systems (p. 11). Chelsea Green Publishing. Kindle Edition] These systems may display their own “intelligence” - a natural evolution of rules and processes based on the intersection of structures - and those emergent intelligences and behaviors may eventually transcend their own boundaries. One example of this is the character of a city or business district. Systems unique to that area will eventually give that area a particular character or flavor, and attract new investment as a result, causing that section of the city to extend beyond its original boundaries. Incorporating Systems Thinking into Structural Agility encourages a holistic approach, where these structures can be examined, analyzed, and can coexist or even overlap without negating each other’s effectiveness.

Dynamic Tensions (or Polarity Thinking [Johnson, Barry. Polarity Management, 2011.]) considers the tensions that arise within organizations when interdependent values or goals appear to be in opposition but can actually be synergistic. When leveraged, these tensions can be generative, creating a virtuous (rather than vicious) cycle, and can lead a team using both/and thinking to discover new, creative possibilities. In contrast, poorly managed tensions can cause oscillation-i.e., an organization swinging like a pendulum between two opposing forces, sapping energy while the organization loses momentum entirely.

What does Structural Agility look and feel like?

Working inside an organization with a high degree of Structural Agility is empowering. Employees feel like their efforts are going into their work, as opposed to strictly structured organizations where they spend unnecessary time fighting the system, or what some refer to as “feeding the beast.” For example, some organizations control their budgets so tightly that getting approval even for small projects is a tooth-and-nail fight. In an organization that has embraced Structural Agility, open communication ensures that the budget is allocated to important activities, and a discretionary budget is kept available to respond quickly to new opportunities. Employees can spend their time working on funded projects instead of battling to prove that their projects are worthy.

Working inside an organization with a high degree of Structural Agility is empowering. Employees feel like their efforts are going into their work, as opposed to strictly structured organizations where they spend unnecessary time fighting the system, or what some refer to as “feeding the beast.” For example, some organizations control their budgets so tightly that getting approval even for small projects is a tooth-and-nail fight. In an organization that has embraced Structural Agility, open communication ensures that the budget is allocated to important activities, and a discretionary budget is kept available to respond quickly to new opportunities. Employees can spend their time working on funded projects instead of battling to prove that their projects are worthy.

Structural Agility creates an organizational “resonance”, where the structure, the people and their work are all in tune. In Physics, resonance can be defined as a situation that occurs when a system is able to store and easily transfer energy between two or more different storage modes, such as kinetic and potential energy. When the structure is made up of the people who created it, a natural resonance occurs, and contributes to a state of flow throughout an organization. One result of uniting structures and people is amplification: an increase in energy throughout a system that occurs when frequencies are resonant.

Another consequence of creating structures that communicate, adapt and self-support is that natural hierarchies begin to emerge. The concept of hierarchies has been villainized due to associations with power and superiority in the workplace, but hierarchy is merely the organization of systems and subsystems. The fifth principle of Structural Agility states: “We enable flow through hierarchies which are naturally in service to each other,” implying an equal and necessary give and take. These sorts of natural hierarchies exist all around us: for example, a tree has hierarchy in the trunk, branches, leaves and buds, but the trunk is not the boss. The leaves bring food to the roots via sunlight and the roots send nutrients to the leaves, all in service to one another to maintain the overall health of the tree. In the same manner, hierarchies arise inside organizations to enhance the flow of materials, information, and resources throughout a system. These emergent hierarchies can reduce imperfections and structural frictions, without placing one team above another or imposing any sort of superiority.

While some frameworks claim to feature no strict hierarchy, what they have attempted to remove is “superiority”. Structural Agility allows everyone inside an organization to contribute at the same level, because no level of the hierarchy has power over another, and all exist to serve. Hierarchy balances the welfare, freedoms, and responsibilities of the subsystems and total system. It ensures enough central control to ensure teams can coordinate in pursuit of the large-system goal, while giving them enough autonomy to keep all subsystems flourishing, functioning and self-organizing. In a natural hierarchy, teams will organically assume the shape and scope that work best for them: broad and shallow, deep and narrow, or some form in between. Structural Agility provides all these types of teams the stability and adaptability they need, and simplifies and streamlines the flow of information between systems.

Leveraging Dynamic Tensions for Flow

“What are dynamic tensions, and how can they be leveraged?”

The fourth principle of Structural Agility states: “We thrive by leveraging dynamic tensions.” What are dynamic tensions, and how can they be leveraged?

As previously mentioned, a tension (also known as a polarity) exists when interdependent values or goals appear to be in opposition, but can actually be synergistic. One example is breathing: exhaling and inhaling are interdependent, and yet may feel opposing. The inhale and the exhale are structurally connected by the lungs and oxygen delivery system. Both are necessary. If you choose to do only one, you’ll die.

The term “tension” is used because these connected forces contain or create energy via their opposition. When wielded creatively, these tensions and energies can produce new possibilities. When framed as a binary choice, these tensions do the exact opposite: creativity is shut down and the system flounders. Tensions create paradoxes which are natural in the landscape of high complexity environments. To thrive in the level of complexity of today’s business landscape, organizations need to learn how to 'hold the paradox’ using both/and thinking.

In practice, organizations can leverage tensions by first naming the tensions at play. Once named, the organization can see the tensions and talk about them. People can then collaboratively define the hope and fear for each tension, thereby uncovering hidden dynamics. From that point, the organization can continue learning and decide on actions to take or structures to adapt.

A common misconception when discussing both/and thinking is that it means an organization can never say no, or that they need to do everything, all the time. This is untrue. Not being selective with projects and processes results in businesses diluting their own impact while forcing employees to work twice as hard. “AND” doesn’t mean an organization must always compromise when faced with a choice between two options. Rather, it asks them to be creative about considering both. “Both/and” thinking can open up new possibilities when faced with challenges that seem unsolvable due to complexity. “Either/or” thinking can reduce friction when we are faced with a problem to solve. Neither thinking model is automatically the correct path. Leveraging dynamic tensions means we use both “both/and” and “either/or” by mindfully holding space for a tension’s coexistence. This creates a multiplicity of possible scenarios, options and ways to respond to change.

Organizations that rely more heavily on “either/or” have a tendency to oscillate or “lurch”. This is the organizational equivalent of gasping for air. When the pendulum swings, the organization spins in place. Structural Agility creates awareness of the tensions and uses them to promote positive energy flow and generate new possibilities.

Types of Tensions

Many types of tensions can exist inside an organization: tensions between processes, practices, business outcomes, mindsets, emotions, and so on. They exist at all levels of systems: individual, team, organization, enterprise, and the larger ecosystem. They vary from a temporal perspective, meaning that some come into existence in a day while others grow over years. Tensions can change over time and have different meanings in different timescales. Structural Agility doesn’t limit the organization to seeing “business-only tensions”. For example, if an emotional tension is present, it’s best to address and resolve it in a way that advances both the organization and the individuals.

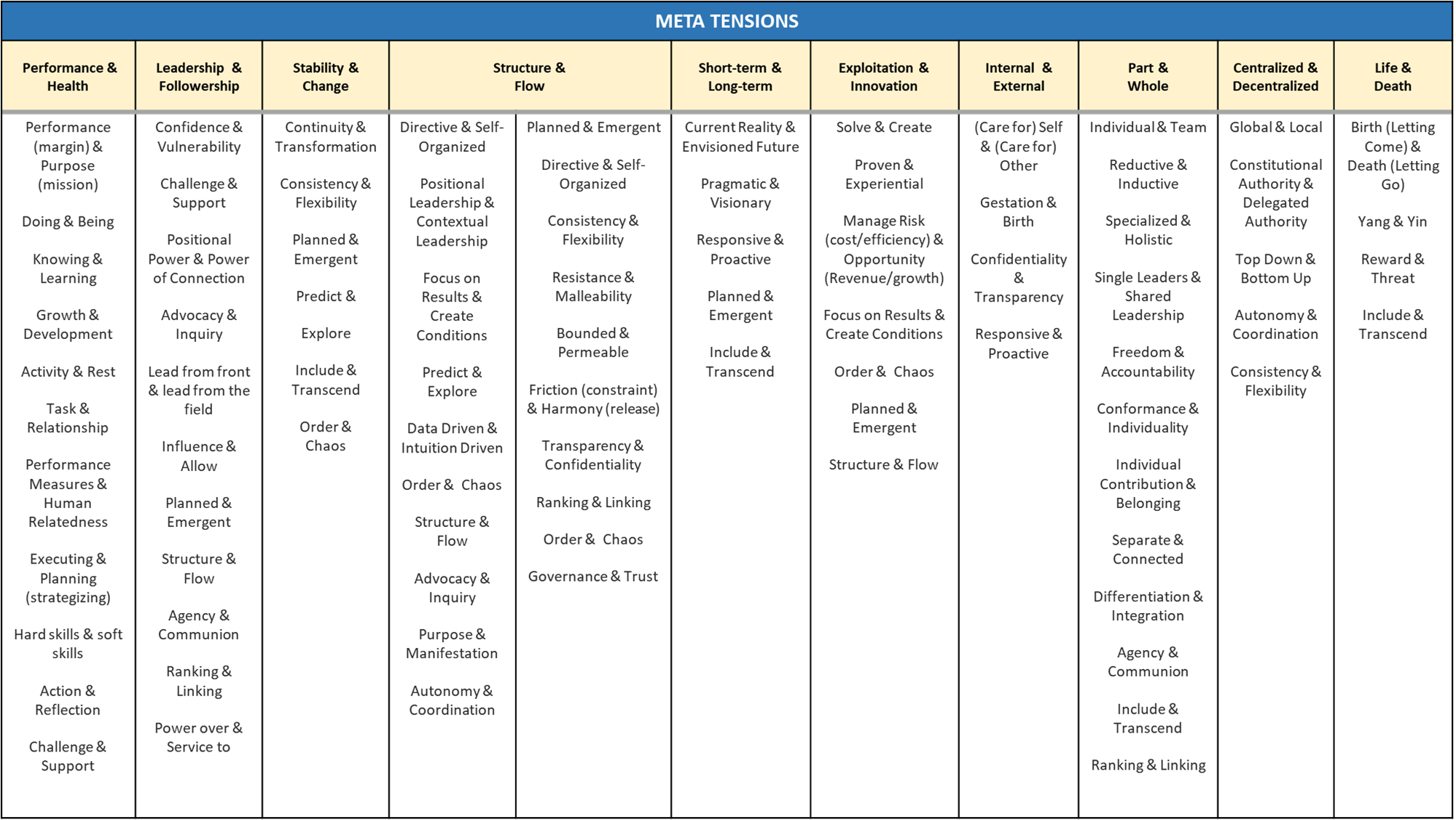

Meta Tensions

There are some tensions common to many organizations, known as Meta Tensions, that are core to the operation of that organization. While not every organization will find every Meta tension applicable, comparing this list against those Tensions common to your organization may provide clarity on how those tensions can be leveraged. The end of this section contains a more detailed list that can help identify a more specific tension.

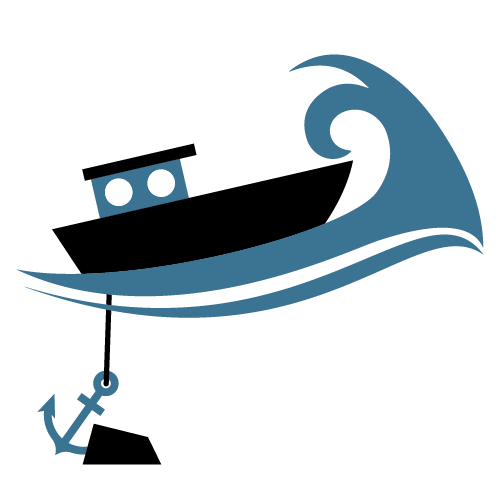

The list of Meta Tensions can be organized into two categories: World-View Tensions, and Manifestations. The three World-View Tensions relate to how an organization structures itself and shapes its identity. The other seven Meta Tensions point to ways the World-Views manifest. They may appear as clearly linked to the World-View Tension, or as their own tensions, to be managed and leveraged independently of the larger Tension at play.

WORLD VIEW TENSIONS

Performance and Health is a tension between the force that gets an organization where it needs to go, and the force that keeps the organization in good working order. This can be visualized as a car’s GPS versus the dashboard [Credit: Bryan Tew]. The GPS guides the car along the most efficient route, while the dashboard helps keep the car operational. A driver that only looks at their dashboard has an understanding of the car’s condition, but has no idea where they’re headed, and vice versa.

Performance and Health is a tension between the force that gets an organization where it needs to go, and the force that keeps the organization in good working order. This can be visualized as a car’s GPS versus the dashboard [Credit: Bryan Tew]. The GPS guides the car along the most efficient route, while the dashboard helps keep the car operational. A driver that only looks at their dashboard has an understanding of the car’s condition, but has no idea where they’re headed, and vice versa.

Leadership and Followership is a tension between pointing the direction and creating supportive conditions, and effectively working towards moving in that direction. This tension is not about formal roles, but what the organization needs in the moment to thrive. An individual can be both a leader and a follower, and neither can succeed without the other.

Leadership and Followership is a tension between pointing the direction and creating supportive conditions, and effectively working towards moving in that direction. This tension is not about formal roles, but what the organization needs in the moment to thrive. An individual can be both a leader and a follower, and neither can succeed without the other.

Stability and Change describes the tension between how organizations need stability to operate, while also being ready to change and adapt when necessary. Current trends are causing conflict in this tension, where those advocating for stability are separate and pitted against those pushing for change. A generative tension energizes people with shared purpose and helps them work on creative ways to embrace change while protecting stability.

Stability and Change describes the tension between how organizations need stability to operate, while also being ready to change and adapt when necessary. Current trends are causing conflict in this tension, where those advocating for stability are separate and pitted against those pushing for change. A generative tension energizes people with shared purpose and helps them work on creative ways to embrace change while protecting stability.

MANIFESTATION OF WORLD VIEW TENSIONS

Structure and Flow is a primary tension to manage when designing organizations. In living systems, form (structure) follows function (flow). The key is understanding the function, i.e., what needs to flow in a system and creating just enough structure to enhance that flow. When working together, “structure not only enables flow” it is continuously informed and shaped by flow.

Structure and Flow is a primary tension to manage when designing organizations. In living systems, form (structure) follows function (flow). The key is understanding the function, i.e., what needs to flow in a system and creating just enough structure to enhance that flow. When working together, “structure not only enables flow” it is continuously informed and shaped by flow.

Long-Term and Short-Term thinking is often seen as an either/or, but when we look at different time horizons ‘in service to each other’ decisions become clearer. An example is when a short-term solution will require long-term rework. The long-term side refuses anything requiring rework, while the short-term insists on a quick fix. Step back to see how the quick-fix might serve the long-term. Can the quick-fix generate revenue to fund the rework and other long-term goals? Or will the quick fix undermine the long-term goal and make it harder to achieve later? Looking at the interplay between time horizons can open up new possibilities.

Long-Term and Short-Term thinking is often seen as an either/or, but when we look at different time horizons ‘in service to each other’ decisions become clearer. An example is when a short-term solution will require long-term rework. The long-term side refuses anything requiring rework, while the short-term insists on a quick fix. Step back to see how the quick-fix might serve the long-term. Can the quick-fix generate revenue to fund the rework and other long-term goals? Or will the quick fix undermine the long-term goal and make it harder to achieve later? Looking at the interplay between time horizons can open up new possibilities.

Exploitation and Innovation uses the term ‘exploitation’ in a positive sense, meaning leveraging current assets. An example of this is the sales team that chooses to sell the cash cow product instead of new products (or vice versa). A traditional approach is to incentivize sales reps to push the new products, leaving them an unbalanced economic choice, which detracts from products with proven reliability and appeal. A generative tension might link the products together, helping them sell each other.

Exploitation and Innovation uses the term ‘exploitation’ in a positive sense, meaning leveraging current assets. An example of this is the sales team that chooses to sell the cash cow product instead of new products (or vice versa). A traditional approach is to incentivize sales reps to push the new products, leaving them an unbalanced economic choice, which detracts from products with proven reliability and appeal. A generative tension might link the products together, helping them sell each other.

Internal and External tensions exist between methods of information gathering. Some organizations gather information largely from internal sources, such as employees, while others focus on external sources: customers, vendors, and competitors. There is a danger in becoming too internal facing, but a similar danger exists in an organization unmooring itself from any internal identity and shaping its actions purely through customer feedback.

Internal and External tensions exist between methods of information gathering. Some organizations gather information largely from internal sources, such as employees, while others focus on external sources: customers, vendors, and competitors. There is a danger in becoming too internal facing, but a similar danger exists in an organization unmooring itself from any internal identity and shaping its actions purely through customer feedback.

Part and Whole reflects the tension between the needs of the whole and the needs of each part. The industrial revolution and Newtonian science created an over-focus on reductionist thinking: the process of breaking things down to their component parts to find and fix a problem. In mechanistic systems, this often works. With complex systems, reductionist thinking has unintended consequences. Fixing something in one area breaks something else, as the whole has a different or more complex set of behaviors than its parts. In Lean, this is known as ‘local optimization’ and ‘global optimization’; what’s good for the part may not be good for the whole. In organizations, individuals and teams need to be cared for and considered, and that care needs to be also viewed through the lens of the whole organization.

Part and Whole reflects the tension between the needs of the whole and the needs of each part. The industrial revolution and Newtonian science created an over-focus on reductionist thinking: the process of breaking things down to their component parts to find and fix a problem. In mechanistic systems, this often works. With complex systems, reductionist thinking has unintended consequences. Fixing something in one area breaks something else, as the whole has a different or more complex set of behaviors than its parts. In Lean, this is known as ‘local optimization’ and ‘global optimization’; what’s good for the part may not be good for the whole. In organizations, individuals and teams need to be cared for and considered, and that care needs to be also viewed through the lens of the whole organization.

Centralize and Decentralize is the ongoing tension between concentrated and distributed structures. As organizations grow larger, economies of scale often drive them to become more centralized in order to improve efficiency. An unintended consequence of this is the creation of a collective intelligence that struggles with innovative thinking and local relevance. Today, many organizations are looking to decentralize their intelligence. An example of this is the shift from functional organizations to cross-functional teams. Generative tension looks to leverage the upside of both centralization and decentralization.

Centralize and Decentralize is the ongoing tension between concentrated and distributed structures. As organizations grow larger, economies of scale often drive them to become more centralized in order to improve efficiency. An unintended consequence of this is the creation of a collective intelligence that struggles with innovative thinking and local relevance. Today, many organizations are looking to decentralize their intelligence. An example of this is the shift from functional organizations to cross-functional teams. Generative tension looks to leverage the upside of both centralization and decentralization.

Spawn and Shed is the tension that exists between spawning new structures and shedding obsolete ones. Finding an organization that can balance both these tasks is rare, and it’s more common to see these activities take place in response to a crisis or one-off event. Generative tensions spark continuous reflection on what needs to be born and what needs to die inside an organization.

Spawn and Shed is the tension that exists between spawning new structures and shedding obsolete ones. Finding an organization that can balance both these tasks is rare, and it’s more common to see these activities take place in response to a crisis or one-off event. Generative tensions spark continuous reflection on what needs to be born and what needs to die inside an organization.

Meta-Tensions in Practice

Recognizing what tensions are at play inside an organization, and identifying which tensions to leverage, can help drive structural decisions. For example, an organization may have traditionally preferred centralization over decentralization, but is now pushing to decentralize. The organization has a choice: treat this as a tension to leverage, or as a problem to solve. If treated as a problem, the organization would likely treat centralization as the villain and decentralization as the savior by creating a from/to plan to drive decentralization. On the other hand, if an organization recognizes this tension as something it needs to manage over time, it will influence a completely different type of decision making around structure.

When an organization is considering adopting a new structure, it helps to look past the sales pitch. New structures will often paint the branded structure or popular structural pattern as a universal solution. Instead, it’s important to examine the impact that new structure will have on existing tensions. This can give insight on whether the pattern is a good fit for the organization.

For example, Design Thinking is a popular framework, or set of practices. A small startup with products that are ‘rising stars’ may be looking to shift more energy into ‘exploitation’ than ‘innovation’. The Design Thinking framework may be popular inside the organization for purposes of innovation but will not provide the necessary structural support required for them to exploit their products. Alternatively, an organization might have a single wildly successful product, and have shifted to a structure centered around Exploitation to better leverage that product. In this case, the organization may find it useful to examine their existing structure and find opportunities where Design Thinking is in service to the organization moving forward.

Note that there is no single structural solution, or best practice. Structure is part of a "structural system", which adapts and changes with the organization.

Each Meta-Tension can show up in multiple ways. Here are some more specific examples that might resonate more with some organizations.

Implementing Structural Agility

The key to Structural Agility is in creating a structure that builds itself: a meta-structure. In the language of Emergence Theory this is known as “a few simple rules.”

It’s vital to recognize that all structures are temporary, and that there’s never a ‘best practice’. All frameworks or patterns should be held lightly. Organizations should continuously reflect on their framework and change the conditions if it’s not behaving as expected. Do the rules need to be altered? Is there a policy to be added or removed? Is the work boundary too large or too small? Too open or too closed? Because complex systems have unpredictable outcomes, the right conditions will depend on experimentation.

When considering a framework or structural pattern, the first step an organization should take is to look at whether it upholds the principles of Structural Agility, before examining where it falls on the meta-tensions. Does it lean to one side of a tension? What tensions are blocking flow, and need to be attended to? Whether a framework is a fit for an organization rests in its match to the organization’s intention, rather than what is true for other organizations.

Agile Structures and Structural Agility

Traditional Agile structures were designed to solve a specific set of problems, common in Technology Organizations. These are patterns and may or may not be appropriate for every organization. This grid shows what each pattern addresses and where it might fall short. It is important to remember that there is no “best practice” or “one size-fits-all” solution. Each organization has to make their own decisions, based on internal and external factors, as to what structures will most successfully move them forward.

| Pattern | Description | Where it Helped | Where it Lacks |

| Team-based, Execution Focused | The main people in Agile are the team. The team’s main job is to deliver value. | Lack of efficiency in handoffs and non-repeatable situations. | Risk of individuals losing their identity and motivation. Doesn’t address larger org level. Focuses on execution, lacks focus on holistic strategy. Doesn’t address context, conditions before execution. |

| Stable, dedicated Teams | The work comes to the team, people don’t go to the work. | Project work introduced a lot of churn in team formations. People were simultaneously on multiple teams There was little focus on ’project team building’ and more on work tasks. |

When organizations need to be adaptive and dynamic, stable teams can create rigidity. Can hamper innovation by limiting diversity and cross-pollination. |

| Cross Functional Teams | Teams have all the people/skills they need to complete a unit of value. | Handoffs inhibited collaboration and iterative learning. | Organizations responsible for ‘large operations’ where economies of scale are more valuable than innovation. When you broaden the scope of ‘value’, it’s hard to know how to encapsulate a ‘team’. |

| T-Shaped Skills | People specialize in one skill but can work in other skills too. | Overspecialization was creating too many critical paths and single points of failure. Hard to load balance ‘effort’. |

Not all skills are available to all team members. i.e surgeon, artist, writer. ‘Fungibility’ can devalue human contribution. |

| Self-Organization | Teams determine how to get the work done. | Teams were told how to do the work, and it didn’t meet the business outcome. Teams didn’t discover better ways of solving a problem. |

When there is fear and/or teams don’t know how to embrace empowerment. This one is worth pursuing even when it fails at first. |

Structural Agility Supports Overall Business Agility

The motto of Structural Agility is “structure enables flow.” Structural Agility serves the overall aim of Business Agility; to help organizations become adaptive and responsive. Structural Agility also supports the other Domains of Business Agility just as, in an earlier analogy, a car’s alignment supports all the other systems necessary to make the car operate as designed.

When an organization incorporates concepts from living systems such as identity, permeable boundaries and tensions, they unlock energy that can be used to drive Agility. When we apply Structural Agility in the same manner, it shifts the way an organization approaches everything from leadership to teams, from learning to operations.

By examining existing systems, analyzing meta-tensions and how they interact, and incorporating both/and thinking to spark new creative possibilities, organizations can leverage the principles of Structural Agility to become more flexible, reactive, and better equipped to manage the pressures of changing business environments.

Business Agility Institute, 2020 © 2020 by the Business Agility Institute. This paper is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Business Agility Institute, 2020 © 2020 by the Business Agility Institute. This paper is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

You have NaN out of 5 free articles to read

Please subscribe and become a member to access the entire Business Agility Library without restriction.