Systems Thinking31

From Ensemble to Orchestra

Ashok Mohan, Axel Teich, Sebastian Becker

July 10, 2020

Ashok Mohan, Axel Teich, Sebastian Becker

July 10, 2020

How agile thinking enabled us to preserve the strengths of a small company whilst growing into a multinational organization.

How agile thinking enabled us to preserve the strengths of a small company whilst growing into a multinational organization.

Authors: Axel Teich, Ashok Mohan, Sebastian Becker

If you would like to discuss this case study with the authors, please connect with them over LinkedIn. They are looking forward to hearing from you.

The challenge: As Ableton grew as a company, collaborating effectively across different teams became vital in order to succeed. We had to reorganize the work of the controlling, finance and other teams outside product development so we could hold on to our entrepreneurial spirit while managing the challenges of organizational growth.

The approach: Our teams adopted agile planning methods from the bottom up, in order to align our priorities and focus and overcome a phase of feeling overwhelmed by a number of parallel growth-related works-in-progress.

The outcome: Our teams kept the dynamism and proactivity of our start-up phase, while developing methods to deal with the coordination and collaboration needed to accommodate our increasingly specialized teams.

What got you here won’t get you there: when a company outgrows its startup phase and becomes an established organization, its criteria of success often change. The very behavior that once made it successful may be a serious roadblock today.

While development and design teams frequently embrace agile methods in their work, it is less commonly used outside product development. By adopting agile methodology in our finance teams, we have found a powerful way of preserving some of the strengths of a small company, while overcoming the challenges of a grown organization. Here we will tell the story from Ableton’s finance team’s perspective.

First, we present an overview of our working environment to give you an idea of why the agile methodology was effective in overcoming the challenges we were facing. We go on to illustrate the impact of the changes we made by example of an individual team member’s work, before and after we adopted some new processes. Finally, we have an in-depth look at the process of change itself: how did we affect change, and what provided us with the momentum we needed.

Customer and product focus | Ableton makes Ableton Live, software for making and performing music; Push, a hardware instrument; and Link, a technology for jamming with laptops and digital instruments. Our highest priority has always been to create value for our customers. Improving our administrative processes and backend infrastructure did not receive sufficient attention and deteriorated over time. This became a critical problem when we established new entities and acquired Cycling ‘74, with little time to adapt.

Growth | Ableton keeps growing organically, which leads to an ever-increasing degree of complexity, such as a growing range of products, more employees and offices, and more varied distribution strategies. To meet our changing requirements, such as setting up a scalable IT system or transitioning to corporate reporting and group planning, we needed a high degree of novel, non-recurring cross-functional project work.

Legacy infrastructure | Our organizational structure, IT systems and internal solutions have grown organically over the years. In particular the self-built IT landscape for bookkeeping, consolidation, reporting and analysis was in bad shape, causing major and growing inefficiencies within our teams.

Decision process | We embrace an inclusive decision-making process that includes our employees’ diverse views. This does, however, limit our ability to intervene top-down, can add significant amounts of time to the process, and makes the standardization required to grow in a scalable manner particularly difficult to set up.

Interdependency | Ableton’s products are built to complement each other and increase each other’s impact. Developing, refining and marketing these products means managing a lot of interdependencies, so we have a vital need for coordination across our various teams.

My name is Tim and I am a long-standing member of Ableton’s finance team. Our fast growth presents me with a continuous stream of new projects and challenges, which I enjoy because I am constantly learning and contributing to Ableton in novel ways. I really like my work, but have been feeling a little overwhelmed of late.

Friday’s are no-meeting days for me. I have managed to organize my week so that I take care of my operational responsibilities from Monday through Thursday, and use Friday for projects and opportunities that come up as the company grows. I initially struggled to create this space for myself. The maintenance of processes that my team is responsible for takes a lot of time. This includes self-built IT infrastructure for financial data, routine reports for other teams, data requests and analytical support. I do not mind the maintenance, but often my limited time only allows for quick fixes of bigger problems.

On Fridays I like to clear my mind by taking 30 minutes to process my inbox. Today there was just one new request. One of my colleagues needed some analytical support to learn about growth opportunities in Brazil. I let him know that we could have a look the following week, added an entry to my to-do list and got ready to start.

In order to focus I decided to spend two hours each on some recent projects: a workshop on aligning revenue projections and sales targets, my proposal for overhauling our cost center logic, and assessing reporting implications of our new bookkeeping software. At the end of the day I felt great. I had managed to make progress on all projects, despite not receiving some needed input from my colleagues on revenue and sales interaction. Despite not getting much work done on it, I had also managed to take a long-overdue look at our personnel planning process.

While Tim works a lot – and feels productive – the mindset that was once key to the success of the team, coupled with the challenges of a growing company, has now turned into a severe roadblock:

Startup mindset: Tim’s proactive attitude was valuable during Ableton’s beginnings. His prompt support in the Brazil matter, and the changes to personnel planning both appear to move things forward. But there are some down-sides. Tim’s colleagues get used to their last-minute requests being handled promptly and do not plan ahead as they otherwise might. Consequently it becomes difficult for Tim to schedule effectively and much-needed time for refining and developing processes is limited.

Increased coordination: Tim used to work with few colleagues in a shared space. As we grew, so did Tim’s team and its work became increasingly specialized and interdependent. In Tim’s example above, he needed his colleagues’ time and input to make progress on financial projections and sales targets. Since they were busy, he started work on another project. What may seem productive at first leads to multiple, unfinished projects running simultaneously. This not only keeps Tim very busy, but also means his colleagues’ projects that require his input do not progress efficiently.

Prioritization: At Ableton, our work on products for customers is often seen as more important than improving internal processes. Tim’s impulse to answer his colleague’s request regarding Brazil promptly – whilst admirable – came at the cost of improving the personnel planning process. This approach leads to less and less efficient processes that take up more of everyone’s time. It may seem obvious to focus on optimizing our processes first, but it takes a holistic understanding of the situation to come to this realization.

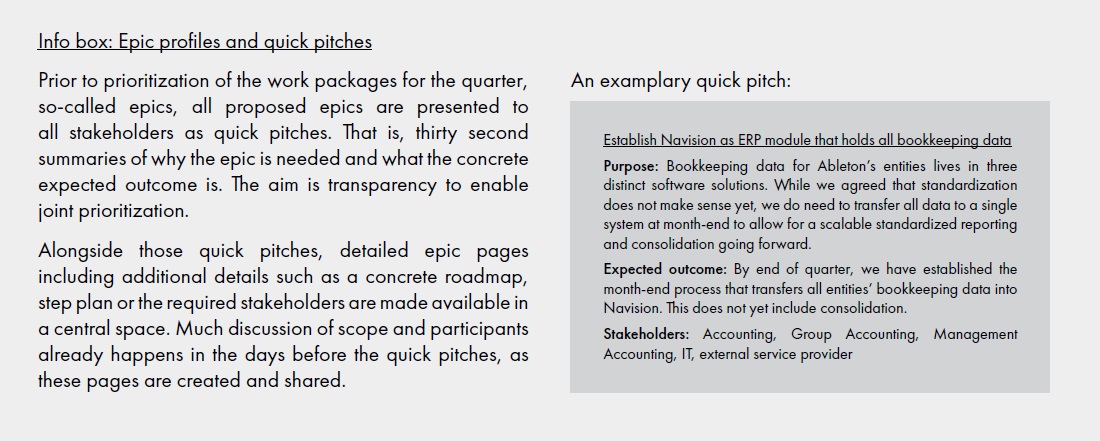

Two and a half years after my no-meeting Friday, my approach to scheduling and prioritizing work has changed dramatically. At the start of a new quarter I am able to study the projects proposed by my colleagues in other Finance teams. We have detailed project profiles that outline their purpose and expected outcomes, and during the preparation phase for the quarter, my colleagues will often approach me to understand the impact of their projects on me and my team.

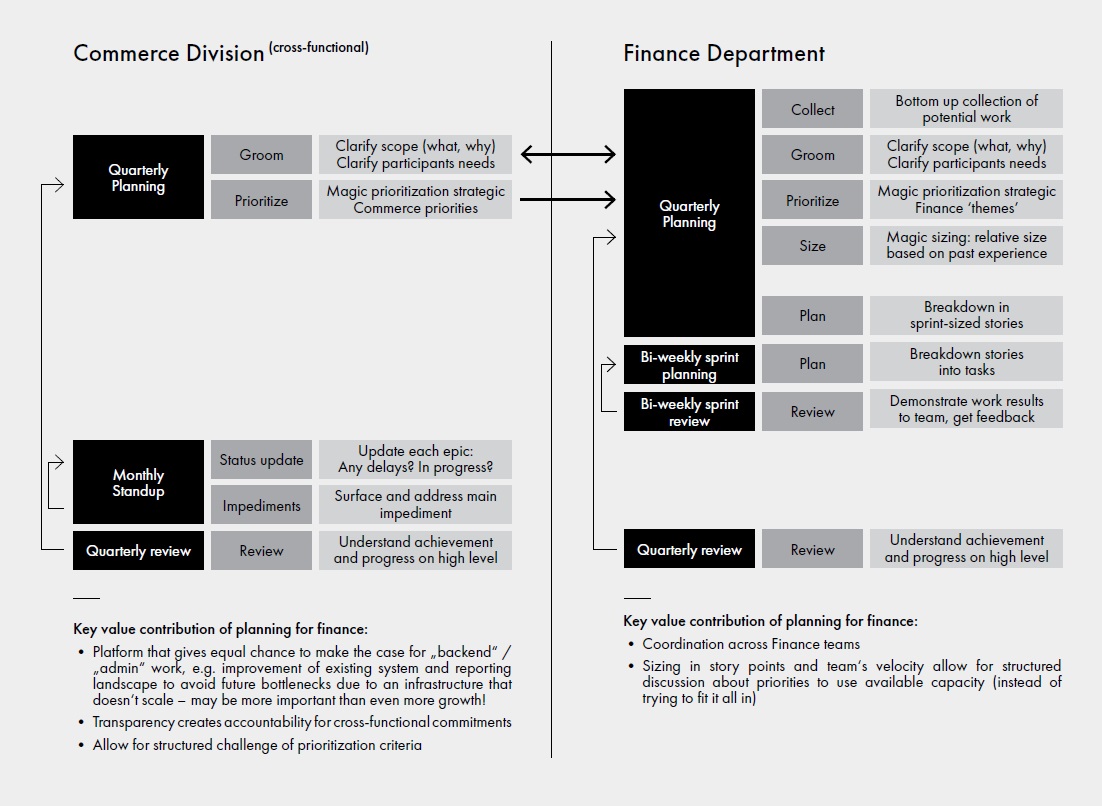

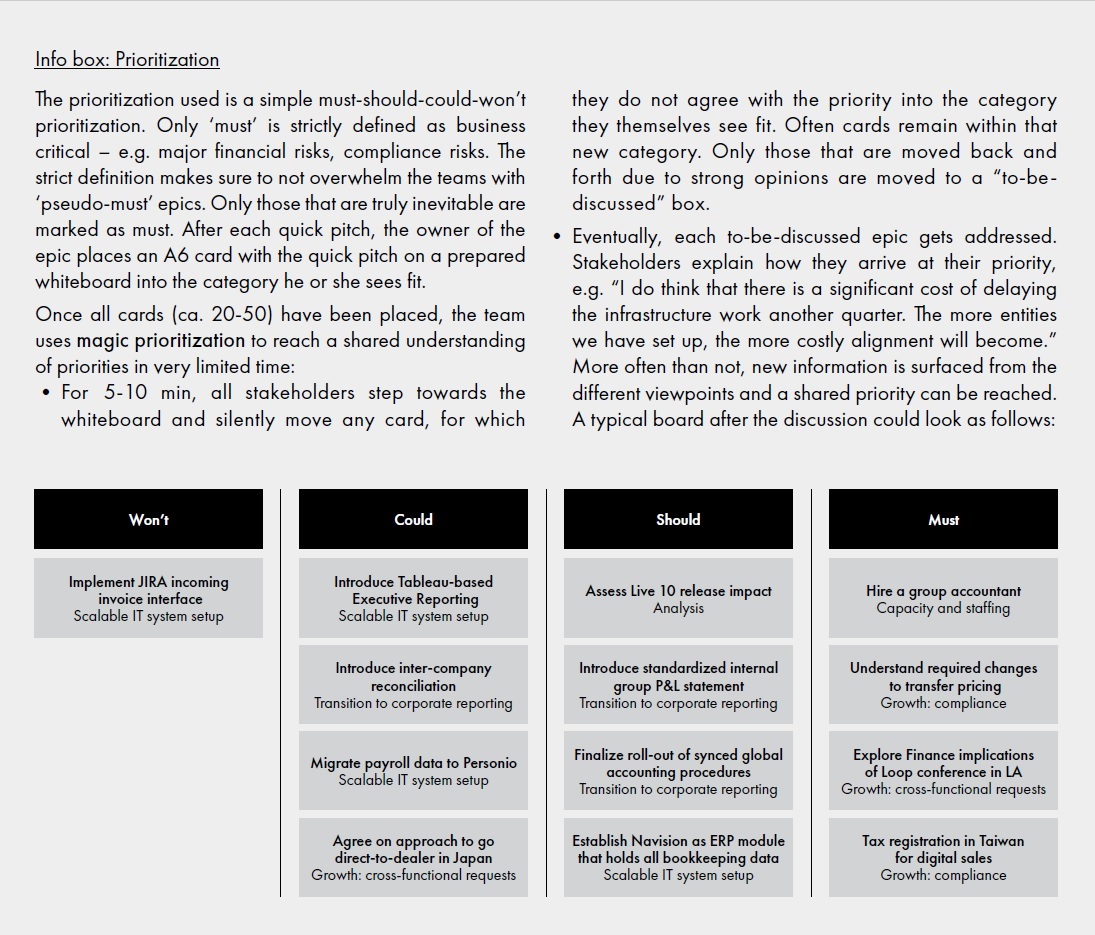

During a workshop at the start of the quarter, myself and other commerce team managers will give quick pitches of our projects to each other – concise versions of the detailed project profiles. We share our reasoning for considering the work a must, could or should, and create an initial prioritization. It is liberating to see that very few projects are truly a must – which we define as business critical – and most are simply opportunities that we are very keen to proceed with. At this point we refine our priorities from the initial list. We apply some agile methodologies like magic prioritization, and only discuss projects that require it, emerging with a list of proposed projects for the quarter that is ordered by relative priority. The preparation phase means that each team is aware of their required commitment for each project.

The next step is to plan my team’s work. Only once we have planned our work for the quarter – in a team-specific and cross-functional way – are we able to say how much work we can commit to. We cannot change the relative priority of cross-functional projects, but we do decide on our capacity to be involved. Our decisions are then fed back to a cross-functional steering group that confirms the plan for the quarter.

Recently, one of my colleagues approached me with an initiative they had been working on: gift cards for web shop customers. My colleague was not aware of the implications for the finance team, so we sat down to update the project profile and compared the project to the work we had already committed to for the quarter. In the end we decided that it was not necessary to re-prioritize and that the project would be proposed again at the start of the next quarter.

Most notably, the process has changed: instead of taking initiative and starting new tasks independently, Tim and his colleagues now decide collectively which projects to pursue. Some aspects of their new approach deserve a closer look:

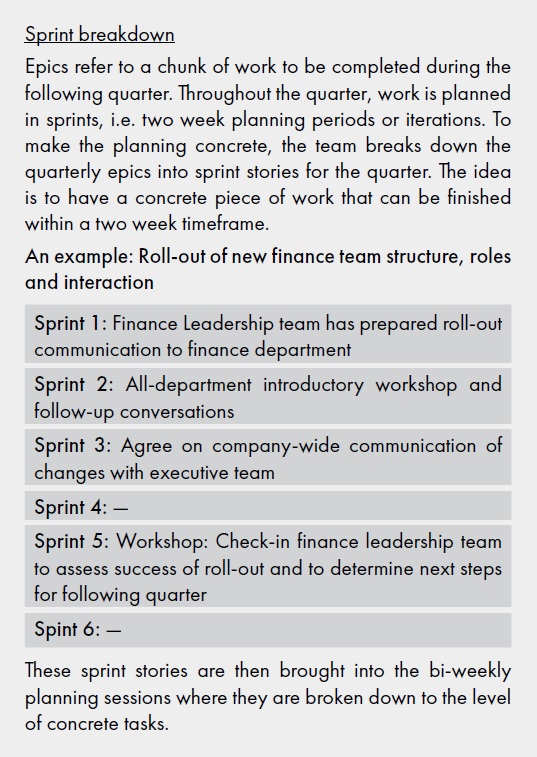

Transparency Throughout the quarterly cycle our teams make jobs and their priority transparent through project profiles. This helps Tim and his colleagues to understand the content and purpose of all tasks. They work in two-week iterations – sprints – and after each sprint they can provide feedback on the project. At the end of each month they examine the progress made in a sprint review.

Mindset Our finance teams have begun to understand their work within a larger context – holistically – due to their shared accountability and ownership of projects. They are clear on the purpose and extent of their own work, as well as that of their colleagues. The iterative approach – continually examining progress and adapting – encourages our teams to aim for continuous improvement, rather than a perfect end goal.

Effects Tim and his colleagues can challenge priorities they do not agree with in the bi-weekly and monthly reviews. They work with greater focus and tackle problems effectively because the scope of each project was set early on, which leads to a realistic estimate of how much work they can commit to. Fewer, and more relevant projects are thus committed to, and our teams avoid running into bottlenecks.

Here are some of the challenges that arose as we became a bigger company:

At the same time, we knew we wanted to hold on to some vital strengths from when we were smaller:

The new approach helps Tim and his colleagues to tackle the challenges we face as Ableton grows. They can focus on fewer and more relevant projects instead of starting multiple parallel works-in-progress that they do not have the capacity to design from the bottom up and follow up throughout. Pilot programs and testing have replaced theoretic discussion about the value of projects for initiating major changes. At the same time, they have managed to preserve a proactive mindset, a collaborative spirit and can react to new challenges quickly.

Ableton’s software development teams adopted Scrum – an agile framework – back in 2008 in response to a product quality crisis. Our internal IT teams were also quick to use the new methods. However, they remained the only practitioners for a long time.

With the added complexity that comes with growth, our finance teams were struggling to implement the changes they saw as necessary. They had built a substantial amount of systems and infrastructure that no-one fully grasped anymore: Were the monthly reports for sales really needed? Should the controlling team really be building the data infrastructure themselves? They were also facing unique challenges, such as setting up subsidiaries and permanent establishments, standardizing bookkeeping for Ableton globally, and developing financial projection and analysis to suit our decision-making processes, which are shared and not driven by financials.

Our teams increasingly found themselves overworked; delivering quick fixes rather than thought-out solutions and trying to meet every request put to them. They were initially convinced that their work was too complex to effectively plan; that agile methods could not be applied to their particular challenges.

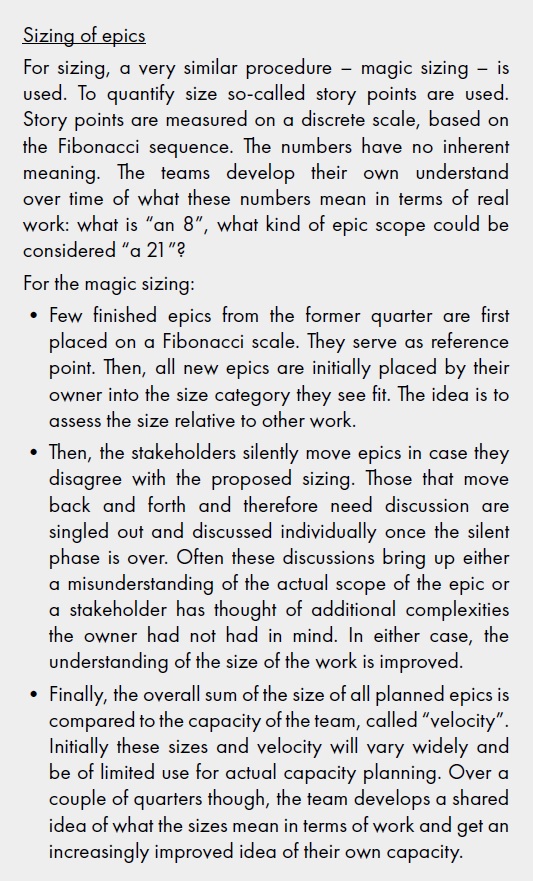

In one quarterly planning session we asked our IT and Finance teams why they could not meet their colleagues’ requests. The IT team member had a simple answer: their capacity – measured in so-called story points – was already committed to other work. If the requests were more important than the work already committed to, then we could meet and take another look at our priorities.

The finance team member was also convinced that they were incapable of taking on more work, believing the team to be overwhelmed with other requests. But since they did not have a system in place that could help them assert this view convincingly, they ended up taking on additional work.

We sought the help of coaches that had helped companies adopt agile methods before and knew how to overcome the initial suspicion of our teams. They taught our teams how to slice their work, estimate capacity using story points and plan their sprints and quarters. Soon, supply chain management, sales and finance, as well as facility management teams had adopted agile methods. With expert help from the coaches, our overwhelmed and overworked teams began to see the benefits of agile planning. Many felt empowered and the initial skepticism faded.

Despite the progress, we faced another, growing challenge. The teams were still overwhelmed with work. They had a better grasp of their own capacities and began to see how little progress was made on the projects they would start. As an attempt to make some meaningful headway, they would start more and more projects. Consequently, much work was started and little was finished.

A sense of much work and little progress was shared across the teams. As a result, for the first time in Ableton’s history, all our middle-managers of the teams with the most challenging interdepencies met with the intent to face and solve the problem. Too many projects running in parallel was voted the biggest obstacle, closely followed by teams setting their priorities without regard to other teams.

The meeting gave birth to the Commerce Steering Initiative. Its purpose is to align priorities across teams and reduce the number of projects running at the same time. To this end, teams bring proposals that require outside contributions for the upcoming quarter to the steering meeting. Project profiles make transparent why a project is relevant to Ableton, what the expected outcome is, who is needed to what extent and how a project team will work together. The cross-functional group of managers jointly prioritizes the proposals based on the project profiles and aligns priorities, ensuring that all teams are aware of what is needed and what they are expected to contribute.

Over time, a continuous improvement loop became an essential part of the process:

Having established our steering groups, we believe we have reached the limits of what process changes can achieve. We are convinced that a larger reorganization is necessary to truly transform the way we work. To this end we formed an initial working group with leaders from diverse functions, including executives, to find a novel solution to organize around cross-functional teams that can deliver end-to-end with few dependencies. This work is in progress and we will start making changes in early 2019.

If you are curious about the details of the processes laid out in this article, feel free to get in touch with us at [email protected].

Axel Teich accompanied Ableton’s finance department’s growth journey from a small company with self-built infrastructure to a multi-national corporation. First, as trainee, later as management accounting team manager, now as head of finance. His experience lies with growth & reorganization of organizational units of varying sizes and in the spirit of business agility, transforming the system & reporting landscape and creating novel finance solutions that meet the demands of a non-financially-driven company.

Axel Teich accompanied Ableton’s finance department’s growth journey from a small company with self-built infrastructure to a multi-national corporation. First, as trainee, later as management accounting team manager, now as head of finance. His experience lies with growth & reorganization of organizational units of varying sizes and in the spirit of business agility, transforming the system & reporting landscape and creating novel finance solutions that meet the demands of a non-financially-driven company.

Ashok Mohan is a Coach with a mission to help create the next generation of organizations needed to succeed in today's complex and changing world while fostering environments where people can thrive. He considers it his life’s mission to build such organizations that enable individuals and teams to express the best versions of themselves. He believes that this generates joy and fulfillment for individuals and as a consequence, ensures the sustainable success of the organization.

Sebastian D. Becker, teaches performance management and entrepreneurship in MBA, executive and other programs at HEC Paris. In his research, he has a particular interest in how management processes such as budgeting, forecasting and innovation accounting can help corporations and startups become more adaptive.

Sebastian D. Becker, teaches performance management and entrepreneurship in MBA, executive and other programs at HEC Paris. In his research, he has a particular interest in how management processes such as budgeting, forecasting and innovation accounting can help corporations and startups become more adaptive.

Please subscribe and become a member to access the entire Business Agility Library without restriction.