There have been so many great talks, including the one that just finished. I'm a great believer in retrospectives, and there are so many things I’d love to pick up on that others have said. However, I promised our Canadian managers that I would tell this story—so here it is.

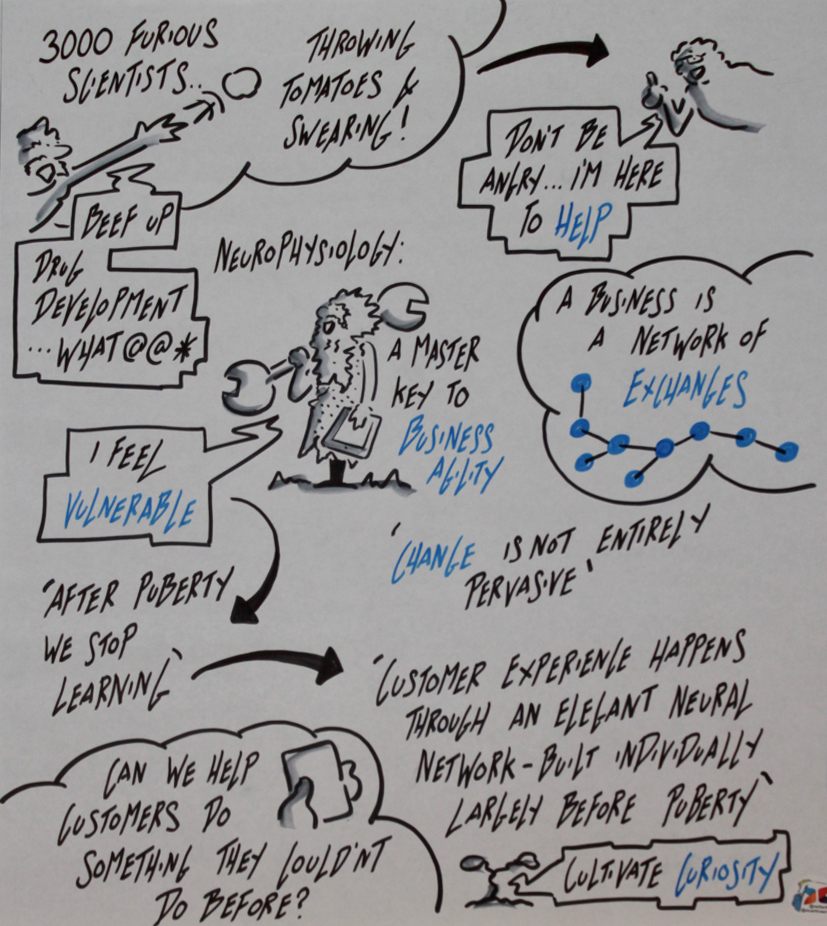

The Story of 3,000 Furious Scientists

When I first entered a Fortune 100 company, I spent my first day doing a bit of discovery. I spoke to the SVP of the research division, and before I even finished saying "Hi, how are you?" he handed me a video and said, "Tell me what I did wrong."

"Okay, what do you think you did wrong?" I asked.

"I don’t know, but they were throwing tomatoes, they were throwing eggs, and the worst thing—they were swearing. People around here don’t swear!"

That same day, I met the head of HR—a gentleman in a handmade suit and handmade shirt. He wasted no time in telling me, "We have the best scientists that money can buy. Any other questions?"

Hmm. No, I didn’t have questions. But I thought to myself that perhaps he hadn’t asked enough of his own.

Meeting the Most Furious Team

I went back to the SVP and asked, "Give me the team you’re most worried about."

"Oh no, I can’t do that. There are 35 of them, and they are the angriest people in the organization."

"Those are the ones I want," I said. "Tell me again, why do you think they’re so angry?"

"Well, we have a new CEO, and he told me what we have to do. So I went and told them."

"And what did the CEO say?"

"We have to beef up our drug development pipeline."

"Anything else?"

"No, that’s all."

It took some convincing, but I finally got approval to work with the team. The SVP insisted I take a male colleague with me, as he wasn’t sure I would be safe. Scouts honor—I could not have made that up.

Transforming Anger into Innovation

So, I walked into the room where these scientists sat, arms crossed, visibly skeptical.

"What do you know? You don’t know anything. Consultants always want to talk about process, and you don’t know anything."

"You’re absolutely right," I told them. "Not only do I not know anything about cancer drugs, I can’t even spell the fields in which you did your postdocs. But I do know a little something about inquiry, and if you’re willing to work with me today, I think we could make some progress on a more efficacious way of developing a cancer drug."

I added, "I have a horrible memory for names, so if you leave right now, I won’t be able to report that you were ever here. Feel free to leave now or anytime during the session."

Not a single person left.

For the first 10 to 15 minutes, they were still angry, and there was still swearing. But then, something changed. The swearing stopped, and they began engaging in the discussion. By the end of the session, they had developed something completely radical for that time. These were the best scientists money could buy, all postdocs who had grown up in an environment where success was measured by how long they could keep their grant funded. The most prestigious among them had essentially blank-check grants.

By the end of that day, they had made a fundamental shift. They decided that a more effective way to develop cancer drugs was to see how quickly they could fail them. This approach transformed the organization.

I didn’t have to do anything else—the change spread like wildfire. These were the most prestigious and the angriest people in the organization, and their influence cascaded throughout the entire company of 3,000 scientists.

The Anthropology of Business

Where I come from, we call this business anthropology. It’s a different way of looking at business—not through the lens of traditional structures, but as a network of exchanges.

From my perspective, the fundamental nature of human exchanges hasn’t changed in the three or four million years our brains have been developing. Exchanges are based on vulnerability. How do I know that?

Our early ancestors lived in an environment where the climate was drying, and they were constantly threatened by predators. They had to work together to keep the lions from eating their children. This challenge required cooperation and inquiry.

Understanding the Brain’s Role

The brain operates as a network, just like any other network. The primary hubs in that network are built before puberty, which is why it’s so hard to learn a language without an accent after a certain age. The brain evolved to stop learning after puberty because, for most of human history, everything you needed to know for survival was learned by that point.

Additionally, early humans co-regulated—they slept in puppy piles, breathing together. This co-regulation created a deep physiological connection between individuals, something that still influences human interactions today.

Modern Business and Belonging

Now, let’s fast forward. The CEO of Microsoft recently said that we are in an era where companies are spending north of $10 billion on development. That’s why change is so rapid and often overwhelming.

But here’s what’s truly important: Humans have not changed.

One fascinating experiment demonstrated this. Undergraduates were placed in an MRI and told they would be playing a ball-tossing game with two other people. At first, the virtual characters threw the ball to the student, but after a couple of minutes, they stopped and only tossed the ball between themselves.

When the students emerged from the MRI, to a person, they said, "I felt horrible. I felt rejected. They didn’t like me."

This is how fragile we are. If people feel excluded, their brains shut down.

The Key to Business Agility

So, what do we do with this knowledge?

Let’s take a page from a company known for innovation. Their core promise is simple: "Are we doing something that will enable our customers to do something they couldn’t do yesterday?"

That kind of clear mission keeps a company on track, even when faced with overwhelming change.

The Power of Rich and Sweet Spot Exchanges

Over my career, I’ve worked to create environments that promote rich exchanges (where something valuable happens) and sweet spot exchanges (where people contribute their best work). That’s all I do—help organizations build a culture where these exchanges happen naturally.

If there’s one thing I want you to take away, it’s this: Curiosity and inquiry drive business agility.

If you’ve ever had the experience of truly being listened to, you know how powerful it is. When people feel heard, they stick with you—even when you don’t know what to do next. They’ll help you navigate change, even when the market shifts unpredictably.

Final Thoughts

Whatever business you’re in, you are competing through the quality of exchanges in your business ecosystem—not just with customers and employees, but across every connection. If you foster a culture where people feel included, valued, and heard, you will always be agile.

Gracie and I are about to start testing a product that helps businesses listen to their entire ecosystem. If you’re interested in helping us test it, let us know. Thank you!

Our brains, the processors on which we depend, developed in the Stone Age. For 150 – 300,000 generations our ancestors lived (or not) by cooperative exchanges. Over those 3 – 6 million years, larger brains and increasingly complex tools, language, and social systems evolved.

Our brains, the processors on which we depend, developed in the Stone Age. For 150 – 300,000 generations our ancestors lived (or not) by cooperative exchanges. Over those 3 – 6 million years, larger brains and increasingly complex tools, language, and social systems evolved.