Humanizing Business62

How Self-Selection Lets People Excel: The Guide

Sandy Mamoli, David Mole

May 8, 2019

Sandy Mamoli, David Mole

May 8, 2019

The fastest and most efficient way to form stable agile teams is to let people choose their own team. This was a scary prospect when we in 2013 first considered handing over the decision making responsibility to the people affected. Fast-forward six years and self-selection has had a profound effect on the way agile teams are assembled in companies all over the world.

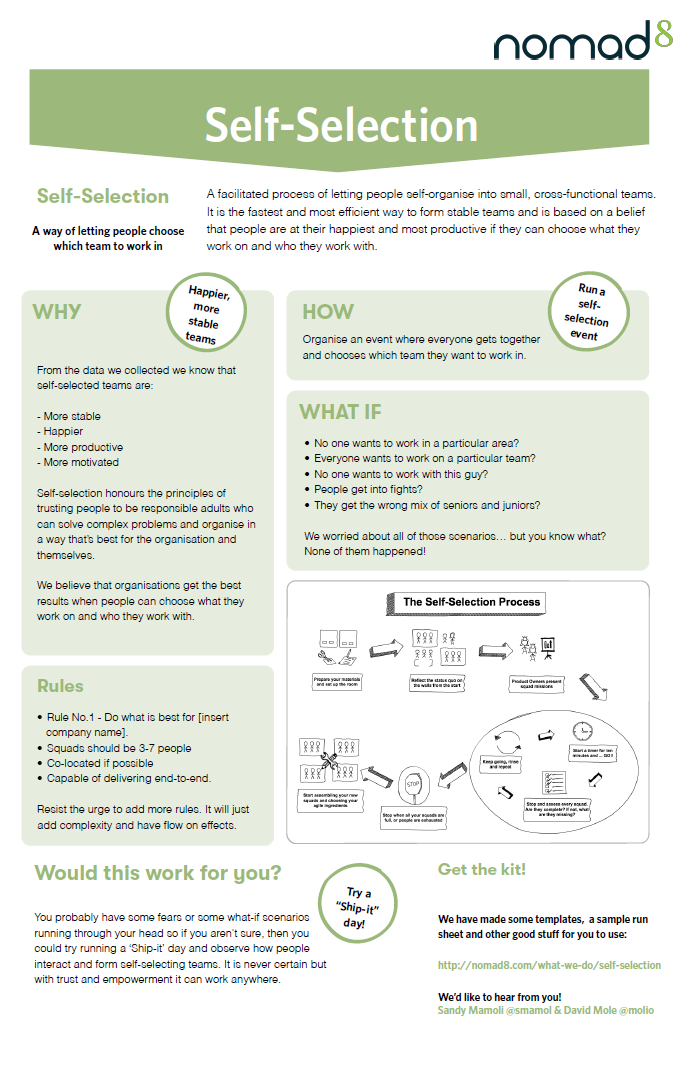

Downloadable Resource: Self-Selection on a Page

Downloadable Resource: Self-Selection on a PageGetting started with Self-Selection: Download a quick guide to self-selection. Download (PDF)

This Self-Selection kit provides ready-made checklists for preparing and running self-selection events of 100 people or more. If you’re fewer people you obviously won’t need as much time and can cut down on some of the logistics and process. This kit is mainly a starting point and you should tweak and adapt it to your own needs. Download (PDF)

Anyone who has ever been on a high-performing team will know what it feels like when a team begins to truly gel, when everyone is committed to and enthusiastic about a shared goal and when people know each other well enough to support and hold each other accountable for great performance. These high-performing teams exist not only in software development but also in sports and in any area where a team of people need to manage their interdependencies while working towards a shared, compelling goal.

Self-selection is a facilitated process of letting people self-organise into small, cross-functional teams. It is the fastest and most efficient way to form teams, based on the belief that people are at their happiest and most productive if they can choose what they work on and who they work with.

To avoid confusion, we are not referring here to self-organising teams. Self-organising teams are groups of motivated individuals who work together toward a shared goal and have the ability and authority to take decisions and readily adapt to changing demands. We like self-organising teams, but that’s not what this is about. Rather this is the process you use to set up self-organising teams in the first place.

When we first started looking into the design of teams, our research suggested that team design was the most important factor in determining team performance. Designing a team doesn’t necessarily mean picking all the best people, but instead it means identifying the best combination of people based on their interdependent skills, preferences and personalities. We looked at two methods of designing teams:

Managerial selection is the traditional way of deciding who should be in which team, used by most organisations today. Managers design teams based on their knowledge of people’s skills, personalities and who they think would get along with whom.

In a small company this often works well - a good manager is aware of relationships between people and knows the skills, personalities and preferences of each of them. Often they come up with team compositions that can be mostly right. It is quick and it is how people expect teams to be designed in most workplaces.

Where this model breaks down is when managers find it difficult to understand the intricacies of relationships between people and their individual preferences. Managerial selection made sense in its historical context of industrial factories where workers’ tasks were relatively simple and repetitive and ‘resources’ were interchangeable, but makes much less sense in the complex, collaborative, creative work of technology today.

At the time of conceiving our self-selection approach the two of us had developed a great partnership and a fantastic working relationship. David was a member of the management team at the large New Zealand based e-commerce company we were working with and Sandy was an Agile Enterprise Coach, specifically brought in to improve the way we worked in technology and as an organisation.

When we first started working together the problems were too much work in progress, everything had slowed and the number of interdependencies between people and projects had brought almost everything to a halt. Our early work together had included developing a Portfolio Kanban approach to managing the work across the company, establishing the very first agile teams and experimenting with different ways of working.

Portfolio Kanban helped us achieve a more manageable amount of work in progress and we saw significant increases in productivity and output as a result. However, we were unable to make any further significant improvements without moving people into stable(ish) teams. Any good working practices from a team were lost when a project ended and the people involved went back into a pool of others. Therefore, we started to solve the problem by getting people into small cross-functional teams, each using their own choice of agile methods.

It had been incredibly positive and rewarding to be part of those improvements but nothing quite prepared us for the work, the challenges and the focus required to invent a self-selection process, to persuade people it would be the best approach and ultimately redesign an organisation from the bottom up.

It was back in 2013 that we formulated our ideas around self-selection and we could certainly have taken the easy route at the time and continued with our existing approach. It had already been a positive journey towards agile and had been both rewarding and enlightening to be part of. Had we decided to continue adding one more team at a time, slowly setting them up for success and coaching them to a level of maturity before moving on to the next team, I doubt anyone would have really queried our approach.

Most agile transformations are a story of change in the face of resistance, coaches who are challenged by those who want to maintain the status quo or refusing to give up their strangle hold on control. Somewhat strangely this was not the problem which led to self-selection at all. We had certainly seen some resistance to change but the successes of the early agile teams had generated great momentum and interest. That meant our problem wasn’t resistance to change, rather it was the number of people who wanted to be part of it!

We were faced with people asking when they could become part of a new agile team and why it would take so long based on our current plan? The reason at the time was us, we had somehow become the bottleneck and found ourselves asking people politely to “please wait” or telling them politely “not now”. We had actually been burned by teams setting off too quickly, where they would skip important steps in how they would work, where they lacked coaching or the team design had turned out to be wrong with hindsight. Going through these experiences had led to us taking a less risky, more controlled approach but we knew at the time that would need to change.

We spent a great deal of time trying to think of new and different ways to approach the problem, ways to look at things differently but we didn’t want to see all the great work we had done regress to the chaos and unlimited work in progress that had preceded it. It wasn’t until we ran one of our quarterly 24-hour hackathons that the solution dawned on us. We had observed at the very start of the hackathon that teams were forming with people choosing their own team, choosing to be part of only one team and immediately forming new bonds with their team-mates.

It was Sandy who first posed the question “Why can’t every day be like this?”. The default retort of course was to laugh and then go back to the problem of how to quickly get people into teams and removing ourselves as a bottleneck. Sandy followed up that “We could really speed this up if we let people choose their own teams”.

We could think of a plethora of reasons why that was a crazy idea - and we have since realised that initially sceptical reaction has turned out to be the default of almost everyone who is introduced to the concept initially.

The key to overcoming our fears was to challenge ourselves with powerful questions:

When we challenged ourselves, none of our worst case scenarios were actually that bad. There were images flashing through our minds of developers wrestling each other on the floor, of people feeling bullied or left out, of complete chaos as we ran our self-selection event and people who didn’t know what or how to choose the right team. However, we knew that with the right process, skilled facilitation and trusting ourselves and the people involved, every potential risk could be mitigated. We also knew that we had made mistakes with management selection in the past, we hadn’t got it right every time, in fact we consistently got it wrong, so could it really be that much worse?

When faced with a significant problem and a complex environment, we did what we would recommend to any of the agile teams we work with on a daily basis, we created a controlled experiment to test our hypothesis and we identified ways to prove or disprove our thinking before we considered doing this at scale. For us that meant a trial self-selection event involving 20 people and forming 3 teams at our satellite office.

When we look back now, I think we were both expecting this to fail and that we had probably missed something significant in our preparation. However, what actually happened was quite the opposite and to this day remains one of the most surprising, positive and important days of our careers. I’m not sure we quite realised the significance of that experiment then and the impact it has had on the company and indeed our lives since. One of the ways we knew that we were onto something significant back came from speaking to the people involved in self-selecting afterwards. They were incredibly positive and glowing about the new found trust and ability to decide their own future. I can’t think of anything else we have done as coaches which has had such a profound effect on the people involved.

By the end of that day those 20 people had formed into teams and we suspected we had created a process that really worked. Of all the things we learned that day, one of the most powerful was that our worst fears were unfounded: there were no fights, no crying in the corner, and no empty teams or people left out.

Having carried out a successful trial we set about creating the main event where the whole technology department would self-select into teams. That meant persuading the 150 people who would take part, that they were best positioned to make these choices. It meant persuading managers to let go of their team selection responsibilities and it meant persuading business units to create clear goals and visions for their teams.

Communicating this well might have been the single most important element to success. We now recognise the pattern when people first hear about self-selection where their initial reaction is fraught with fear and resistance. Fear of something new and different perhaps, fear of what might happen, fear of being stuck in a team with someone you don’t get on with, or not being able to change your mind at a later date.

The most common fears seemed to stem from the self-selection process having a negative effect on the people involved. Fears that they wouldn’t enjoy making decisions or that there would be arguments, disagreements and stalemates. We remember people asking us what to do if they just couldn’t decide which team to join or what we would do as facilitators when people refused to move from an oversubscribed team. Of course in reality people can always make a decision but even if it is difficult or uncomfortable to make the decision, wouldn’t you always be in a better position to make the ultimate call than your manager?

Getting the communication strategy right could be the difference between a self-selection event going badly (or not taking place at all) or being a roaring success. People will always throw a lot of questions and what-if scenarios (as they should!) and we learned a lot about how important it is to be honest, proactive and clear in all communications around something like this.

When we reflect on why our communications seemed to work, we think it came down to these key elements:

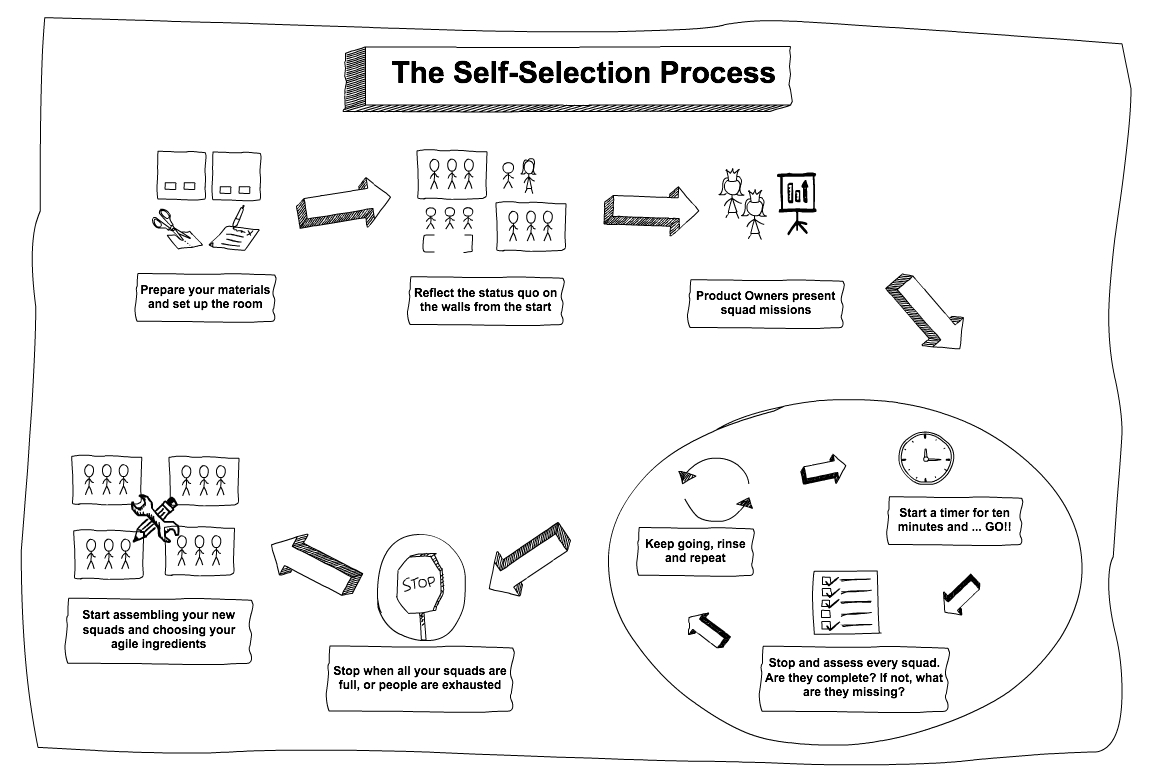

When we first looked into self-selection we couldn’t find anyone in the world who had carried this out at a similar scale. There were some incredible examples from the military during World War II (McKinstry, 2009) but nothing which demonstrated a process that could work for us. That meant we needed to come up with the process ourselves and here you can see a snapshot of a self-selection process.

Figure 1. The self-selection process in a nutshell

The process starts with setting the scene as the desired teams are visualised on the walls and the product owners present their picture of how a team would align behind a shared vision. The key element to success is shown in the circle of Figure 1; the rinse and repeat function which allows people to select and then step back to assess if their choice is going to be successful in the bigger picture.

This kind of inspect and adapt approach seems simple and highly appropriate to agile teams. Each time we have run a self-selection event, and we have run many during the last six years, we have never gone past three rounds of inspecting and adapting before the teams settle into a scenario which they believe is best.

Of course selecting the teams on paper is just the start but the levels of trust process like this creates can be highly impactful later when these teams are established and working together. People who have chosen to work together simply make things work!

It has been fascinating to observe what people have based their selections on during the self-selection events. The single most important factor has always been personal relations – who people want to work with and who they don't want to work with. It can be hard for people to admit this up front though. In a survey we conducted after our largest self-selection event, most people said they had based their choices exclusively on ‘doing what was best for the company’ but that ran contrary to our observations: during the day most of the conversations we overheard were about who wanted to work with whom and we noticed that many people were only available in twos or threes. Often when one person moved, other people immediately moved along with them.

Sometimes people don’t want to work with each other. And that’s okay. People know whether or not they’re going to gel in a team with a particular person and if not it makes sense that they would choose not to work with them. During our biggest self-selection day, we observed two people in particular who seemed to have taken a dislike to each other. When one of them moved their photo to a team the other one was in, the first one would move their photo to a different team. This happened several times and whenever those two coincidentally ended up in the same team, one of them would move again.

Some people can be worried that uncovering these kind of issues can lead to long term conflict or cross team disagreement but in actual fact we have always seen this as the solution and not creation of problems. Prior to self-selection these people would be forced to work together and feuds would have had a negative impact on their team mates and led to managerial escalation. Now these people could choose to work separately and when they did speak or work collaboratively, they would do so in a calmer and more productive way.

After each self-selection we survey people about their experiences and expectations. We ask what they think of the process and whether they like the results. Every single time we have done this, our results have showed that the vast majority of people like the team they end up being part of. Somewhat surprisingly, most people tell us that they now work with the team they expected to work with, so people do certainly seem to go into the day with expectations about the outcome. After the day, almost everyone is in favour of self-selection as the best way to design teams. Even people who initially fear and doubt the process come away with a positive attitude.

It is fair to say that not every single person falls into that camp. There could be one person who made a compromise in their selection which they now regret, or with the power of hindsight they can see they could have made a better choice. That is ok and solving the problem of moving one or two people between teams is a far simpler one that selecting entire teams across an organisation. It is important to note though that the principles of self-selection must carry through to these kind of decisions, empowering the people involved to carry out any follow up action. It would be too easy to undermine the self-selection process for everyone else with one sweeping managerial decision at this time.

The impact of self-selection for the people involved has been far more than simply making the choice of who to work with. We have observed that self-selected teams remain far more stable. We measured the difference between our teams that were selected by managers versus those that self-selected and whilst there were still some inevitable people changes at different times, people remained in their self-selected team far longer than they had before (9 months on average).

Our measurements also told us that happiness and motivation has been significantly higher. We measured this using a short survey that we created based on questions around happiness, the support they were receiving and whether they had autonomy, mastery and purpose - the concepts made famous by motivation expert Daniel Pink in his book Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us (Pink, 2009).

Importantly we found that the output and productivity of these teams also went up significantly following self-selection and we saw an improvement of approximately 20% when compared to teams who were chosen by their manager. Of course measuring productivity for technology teams is hard but we settled on measuring the number of user stories shipped to production as a proxy for measuring productivity. This meant we would have a solid team based measurement of output and the reason we liked and chose this option was because if people tried to game the measure (as they inevitably do with things like this) they would ship to production more often, or they would slice their user stories to be smaller - both of which would be behaviours that we wanted to encourage regardless of measuring productivity.

These are just the quantifiable results; the non-quantifiable elements we have seen are that self-selected teams tend to form work families. Working with people they like and respect has a profound effect on how they approach their work and how much more they enjoy interacting with their colleagues. If someone was to come into the organisation today they would be able to see great collaboration at any time of the day, people out of their seats, working together to solve problems, visualising their work. They would also observe a loudness (sometimes called the buzz around the office) as people talk, laugh and hold each other accountable for what they have said. There is also more honesty and better feedback given amongst teams as people build upon the trust that was established right at the start.

Some people often wonder what happens to the managers in this scenario, for example if you understand that the people themselves will make better choices and ultimately be better off, what do the managers do now that they aren’t spending their time selecting teams on behalf of others? Well, for some, it can be uncomfortable for managers to give up control and relinquish a key element of their job. Their roles can change in this scenario from one of being a manager to one of being a coach and in all honesty that can be more attractive for some people, and not so for others.

These days’ self-selection is the way that teams are selected at our New Zealand e-commerce company, where any significant change in direction or growth drives people to run a new self-selection event. We take great pride from that and additionally from the graduates who know of no other way that teams could possibly be selected!

The company where we trialled self-selection has gone from strength to strength and continues to embrace the principles. Today there is a new self-selection event at least every six months, where even if there is no immediate reason to change people are still offered the chance to assess their decision, to stay where they are or choose a new team.

The company also continues to grow in all known measures of company performance such as revenue, profit, customer base, number of employees. It is not possible to claim that self-selection contributed directly to something like company profit, as there are so many variables in such an environment but we are confident that the changes helped the company navigate a period of growth in an incredibly positive way. To maintain a company culture during growth is no small feat but embodying the principles of self-selection has left an incredibly positive effect.

Today, David has joined Sandy as an Agile Enterprise Coach and offers support to new agile teams at different companies. We work together to support other organisations that have a desire to change the way their teams are designed and when we look back now, self-selection has had a profound effect on our careers. It has led to us being published authors, running dozens of self-selection events and training all over the world. Perhaps most importantly of all though, it has allowed us to work with great people and not only that but to see those people get to work with people they choose on the subject matter that interests them most.

Buy The Book: Creating Great Teams

Buy The Book: Creating Great TeamsIf this reference article inspires you, check out Sandy and David's book on Self-Selection. Buy a copy (Amazon link)!

Please subscribe and become a member to access the entire Business Agility Library without restriction.