Humanizing Business62

Creating Autonomy and Purpose to Bring Higher Meaning to Work

Joshua Vial

June 19, 2020

Joshua Vial

June 19, 2020

Most people spend the majority of their time at work and maybe a small portion of their free time making meaningful contributions to society. About a decade ago, Joshua Vial, a computer programmer by discipline, but a visionary at heart, had an epiphany that work could be meaningful.

Most people spend the majority of their time at work and maybe a small portion of their free time making meaningful contributions to society. About a decade ago, Joshua Vial, a computer programmer by discipline, but a visionary at heart, had an epiphany that work could be meaningful.

As a resident of New Zealand, Vial was deeply concerned about the ecological world and felt that working all day just to earn a paycheck didn’t feel like meaningful work. He set out to find like-minded people, realizing together they would have a greater impact on blending the world of work with meaningful contributions to society.

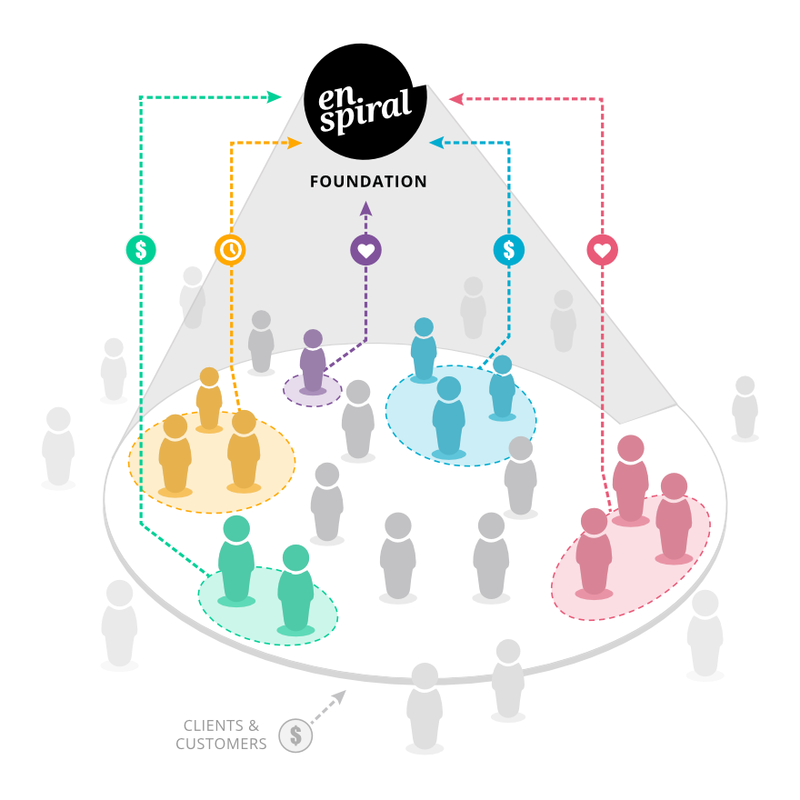

This vision led to the launch of Enspiral in 2010, a collective group of freelance software consultants, which began with 80-100 people that were invited to join. Today it has around 200 members.

“It {Enspiral} provides a community of belonging—more like a friendship group than a business network. It’s for people who want to support each other in their social mission,” says Richard Bartlett, a member of the collective.

Most corporations have their vision and mission statements beautifully etched in their company’s hallways, but that’s usually where it stops. If asked, most employees couldn’t really tell you what their company’s mission is, or if they can it’s because they’ve memorized the writing on the wall.

Enspiral is organized much differently than any corporation, but what really makes it work is that everyone in the collective is united in the vision that Vial had that work could be meaningful. All members are on the same mission to help society and to give back.

Members in the collective don’t just know what the vision and mission are—they are all deeply bound by it and have a strong sense of collective purpose and responsibility to see it through. People that don’t give back and deeply commit to the mission typically get weeded out naturally.

“We’re self-starting people who make a commitment and stick with it. We own up to our mistakes. There’s no manager helping you. We’re weirdos. We’re people looking for something different,” says Bartlett. “It’s very common for people to leave. We only want people there who really want to be there,” he says.

For companies looking to create this culture, it’s important to hire people with a shared sense of purpose, passion and to drive all company decisions around these values.

In recent years, large companies have made an effort to decentralize power and create flatter organizations. At Enspiral, the power has always been distributed with no organizational hierarchy.

The collective is made up of a network of companies and has a few dozen different brands, making up an ecosystem of purposes, all aligned to the larger mission of making work meaningful.

While Enspiral was started by software development freelancers, today the collective has branched into training developers, agile management and consulting and event facilitation groups. The collective has an elastic labor pool, so if you work in one of the companies, you can easily move to another. “People can move across companies and stay within the larger boundary. It keeps the investment in the people,” says Bartlett. He refers to the individual companies as ‘cell boundaries’ with a sense of shared identity.

He also adds that most of the companies are small, about five to 25 employees, so having a bigger family of companies and branding helps with the marketing budget. The collective has a shared brand, shared money and shared decision-making.

Regardless of whether you’re referring to the individual company or larger collective, the idea of ‘boss’ is intentionally absent from the collective. In fact there are only two key roles at Enspiral—members and contributors. About 30 people are members, meaning they’ve been around a long time and can invite others to the collective. Everyone else is a contributor to the organization.

To be a contributor requires more than just a personal invitation—you must be deeply committed to the organization’s mission and want to actively contribute to the greater good in the world, plus you must be trustworthy and self-motivated enough to work hard without a traditional boss.

“We’re on a mission of distribution of power,” says Bartlett. “You can’t draw it on an org chart. We relate to people in a peer-to-peer way and form relationships based on objectives and clients.”

While most companies will never achieve this level of flatness, decentralizing power is one way to get team members to take on more of an ownership role and to feel more accountable for their work. Organizations who allow teams to self-organize are known to produce higher quality work.

In the corporate world, most projects are driven by the top down, coming in as initiatives and then being distributed to various teams or departments who accept the work.

At Enspiral, projects are driven by everyone and can be anything, such as speaking at a conference or funding generosity projects, which are more about giving back to the community than meeting revenue goals.

Because money is distributed among the collective, everyone has a vested interest in the outcome. “If you’re trying to engage people, decisions about money are a great place to do it,” says Bartlett.

Approximately half of the collective’s budget goes to cover costs and the other half is discretionary, set by priorities they choose to fund. The group recently set aside a fund for well-being and conflict resolution, offering counseling and therapy to members.

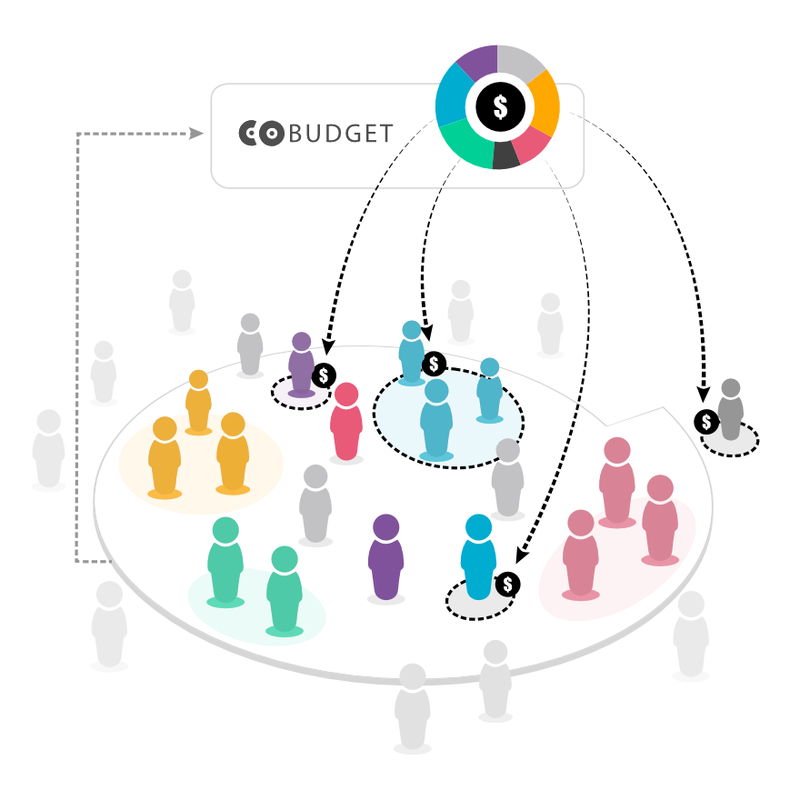

Anyone can submit a project idea, and all ideas are managed by a software program called cobudget.co. The collective members are located around the world, so all project decisions are made asynchronously online rather than in meetings.

“Compared to a meeting it's slower, but people have time to reflect. We get to hear from different people and hear the voices of people who don’t speak up. We get better decisions because people have more space,” says Bartlett.

Project ideas get bucketed into a category, the person proposing the idea says the budget and people who are interested hear the ideas and give each other feedback. If the project gets enough community support, it goes into a funding phase.

They’ve experimented with many different ways to approve projects, but today they use tokens as voting chips. Many members give a lot of their paychecks back to the collective, and those people have more influence in funding projects.

While this seems like a very far-reaching idea for traditional companies, playing with poker chips to fund a project is taught in many product owner classes. The idea is to bring all stakeholders into a room. Project ideas are placed on index cards, each with a ‘cost’, typically derived from story point estimation. Stakeholder chips are divided by influence—a leader who has a more direct stake in this type of work gets more poker chips. There isn’t enough money to buy all of the projects, so negotiation must happen between the stakeholders.

Without management to make decisions, how Enspiral operates is governed by members and happens asynchronously using a tool called loomio.org. It’s a text-based platform and everyone participates in their own time zones.

This decision-making platform addresses decisions such as, ‘How are we going to deal with conflict?’ It’s a process where people share their ideas, which eventually leads to a convergent phase.

When someone makes a proposal on a process, everyone can vote. A time limit is set to make the decision, typically around three days. There’s an unwritten rule of ‘participate now or you’ll miss out’. Often a small committee will form and come back for checks rather than shephard the whole process all the way through.

While it’s not the fastest way to make decisions, it’s a way that everyone can propose ideas and be involved if the topic is something they care about. If the topic is not important to a person, they don’t have to waste endless hours in meetings—they simply don’t participate.

One way to instill this behavior is by making meetings optional to attend and to give people the power to say, if I care enough I’ll show up. If I don’t care, I won’t. You can also incorporate this decision-making process by using a tool like loomio.org or something similar and skipping meetings altogether.

The culture at Enspiral is all about learning from failure and having the freedom to experiment with new ideas.

“It’s an amazing place to experiment and learn and grow. It involves a lot of failure. Two-thirds of our start-ups don’t exist anymore. It’s about the learning process,” says Bartlett. Bartlett says that they create problems on purpose and call each other out when someone doesn’t contribute.

One experiment is a livelihood pod where freelance consultants share their income to avoid the feast or famine cycle that often comes with that type of work.

“All of these experiments have risen from a commitment to shared power,” says Bartlett. “It’s up to everyone to lead.”

To create a culture of experimentation at your company, you need to make sure the team has adequate space. Most companies only plan for deliverables, maxing out their teams’ capacity. If the teams are always racing against the clock, innovation gets shoved aside. Some companies have created innovation sprints, or have left one or two days in the cycle for experimentation.

We typically think that only organizations following an agile framework are practicing business agility, but Enspiral has proven that there are many unique ways that agility can happen. They aren’t agile for their speed, in fact some might say their process is a bit slower, but they truly live up to agility in terms of collaboration, innovation and experimentation.

We typically think that only organizations following an agile framework are practicing business agility, but Enspiral has proven that there are many unique ways that agility can happen. They aren’t agile for their speed, in fact some might say their process is a bit slower, but they truly live up to agility in terms of collaboration, innovation and experimentation.

“We are about business for good and experimenting with a different way of organizing. We dream of what may be the organization of the future. People are waking up to the possibility that we can have it,” says Bartlett.

He adds, “If your mission is to make as much money as possible, it’s not effective. But belonging, purpose and autonomy it’s excellent.”

Bartlett says that culture change starts with psychological safety. The most effective teams share ideas and can disagree with people without having their position threatened. “You have to be prepared to have some uncomfortable conversations and understand what’s causing fear. You are asking for conflict,” he says.

Working as a consultant around the world, Bartlett recognizes the same cultural barriers to business agility happening everywhere. This collaborative model comes pretty naturally to Scandinavian countries, but for very independently-minded cultures like the United States the transformation may take longer.

If you’re looking to become a more agile organization culturally, Bartlett advises really embracing the retrospective process. “Treat retros seriously. Use them as a regular process for reflection and experimentation. Really empower that process so it’s not about the content of the work, but about how people work together,” he says.

Please subscribe and become a member to access the entire Business Agility Library without restriction.