Colleen Kirtland

July 20, 2022

Colleen Kirtland

July 20, 2022

Editor: Christopher Ruz

Sometimes the best way to initiate change is not through direct action, but by deeply understanding and cultivating the natural ways in which people and teams are prone to thrive. If you are interested in learning about how to foster organizational agility without branded “agile frameworks,” then this may help you. If you appreciate natural ecosystems and accept as-is the irreducible mysteries of the universe as an experimental black box, consider this read a curiosity-inducing start to a beautiful journey for yourself and your teams.

For skeptics who worry about process unruliness and those who may demand that science underpin truth, let us pique your interest with thoughts from a few luminaries. Janine Benyus implies that self-organized systems exist in a sweet spot between chaos and order, where we get order for free. Physicist Joseph Ford defines chaos as “dynamics freed from the shackles of order and predictability…systems liberated to explore their every dynamical possibility.” Steven Strogatz believes chaos “amplifies small uncertainties but is not entirely unpredictable.”

As Pacific Life has continued to evolve and change, there are only a few people that remember the early days of agility (before I joined the company in 2015), so we wanted to co-create a record of our story as we remember it before it dissipates into unverifiable mythology.

Our use of multiple analogies is to encourage you to appreciate the diversity, complexity and beauty of our natural world and how it can inspire resilient and lasting agile practices.

To help you get to relevant information quickly, we have structured our sections around key experiments which we invite you to try:

A feature of Pacific Life’s agility is that it did not (at first) start from the top down and therefore began from an initial state that allowed for chaos. No one was there to control it or “Manage Performance” around it. “Agility” as an intended organizational objective did not come until 2020, at least seven years after a pioneering team tried their first Agile experiment. The other key feature of our early development that has influenced our current state is that we did not start with “methods” or “frameworks,” but instead started with the exploration of more abstract behaviors by defining three key characteristics of organizational agility. I am not saying this approach is correct for every team or organization. Any approach is fraught with challenges. For our teams and leaders, the abstraction of starting with broadly defined agile behaviors created frustration because there were not enough tangible, concrete practices and methods to latch on to. We did not follow any single methodology or framework, though we encouraged the study of any and all.

In early 2017 we introduced three key agile mindsets/behaviors:

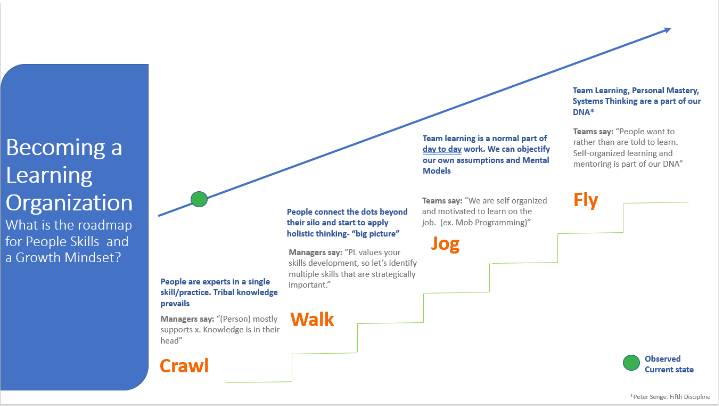

Looking back, it’s amusing that we portrayed the growth and maturity of these mindset values as linear (see historical exhibit below). We’ve since gained a more nuanced understanding of how complex organizational growth might look more like a Poincare Map than it does a linear

I can’t speak highly enough about having latitude to experiment without performance pressure being applied by Management. To clarify, we define Agile performance pressure in this context as external forces that are driven from outside a team or organization’s context. This could be anything from market forces, pandemic disruptions, to even a new disruptive strategic vision developed by external consultants that seeks to change results and organizational culture. Pacific Life’s first agility explorations took place not only before the COVID 19 pandemic, but seven years before “Agility” was formally declared as a desirable organizational goal. Our first tipping point occurred within an experimental context that can be described as a key self-organizing moment.

There is no right or wrong way to start a transformation. I love the wisdom of a well-known Agile Coach who says: “[S]tart anywhere, follow it everywhere.” Organizations are comprised of complex adaptive human organizing networks, like tree roots that wend their way naturally through soil to seek water, survive and self-nourish. We started our journey deliberately devoid of specifically branded Agile frameworks (we called this the “non-canonical” model of Agile, meaning all models were welcome to be explored, but we would not declare allegiance to a single model that would make us vulnerable to getting sold a bunch of packaged training and external consulting). While many agile framework designers believe that their models are meant to be tailored, rarely have I seen organizations understand this. Instead of experimenting with variations on a theme, people try to clone models as prescribed. Cloning is a very dangerous way of stunting development. I like the wisdom of Wendell Berry (farmer and poet) who offers us advice against cloning sheep: “Cloning is not a way to improve sheep. On the contrary, it is a way to stall the sheep’s lineage and make it unimprovable.”

When I started at Pacific Life, we made sure not to carry past mistakes from other companies with us. Having been a part of top down forced structural “Agile” adoption, we were determined to do anything we could to make sure grassroots enthusiasm and curiosity were a part of our agile journey. In 2015, the advice I received was to avoid use of the “A” word because, in a 150-year-old institution, it was likely to sound too trendy and raise suspicion. At that time, the “A” word was something a few teams had tried with little to no holistic support.

This is similar to many other companies that have experienced a small group of enthusiastic pioneers, a coalition of the willing, who are brave enough to swim against the tide. No matter where you decide to start your agile journey, know that muddling is not only okay, but encouraged. There are many highly experienced agile practitioners who would support the notion that forcing ways of working upon teams that simply mimic ideas from a book or one-time certification training (without letting hearts align to tried and true experimentation) is setting yourself up for a huge disappointment. I say this because whatever we have done at Pacific Life up until this point has been a combination of both deliberate avoidance of formal “Agile” and waiting until enough intrinsic desire for change developed. At Pacific Life, agile practitioners are students of complex, adaptive systems. Incidentally, humanity is in the midst of a Complexity Science revolution, where we are yielding to an understanding that our natural world is perhaps irreducible. Chaotic systems, for example, teach us that what may appear random may actually be an expression of an unrelenting impulse toward temporary natural order, whether we see it in the ways flocks of birds fly, or the way in which pandemics make their way through populations.

Who knows how old our universe is? In the book Sixth Extinction, the entrance of Homo Sapiens is said to be comparable to the second before midnight on a 24-hour clock. We humans are but a brief glimmer at the end of a long road of predecessors and antecedents, all part of an even longer story of universal creation. Coming to the matter at hand, we wanted to share a story of some teams at Pacific Life that have taught us how building resilience and agility is a long game that can be played quite successfully, even in traditional and seemingly ossified organizations. About five years have passed since an important tipping point—the moment some of our teams discovered the value of self-organization. For those of us who love to study living systems, we know that more than one evolutionary inflection point is likely to occur, a point that will dramatically alter future trajectories.

Our agility journey thus far has taught us that the ultimate shape of a self-organizing teams will be influenced by both natural laws and chance, serendipitous events. In maturing our agile mindset, we have grown more comfortable trusting wisdom in the present moment to guide us to our next optimal steps, instead of attempting to over-divine what the future may hold for us. Trusting the process of not over-planning is one of the most subtle paradoxes in agility adoption because some believe that trusting natural flow entails a complete absence of planning. This is not true. We plan because we seek ways to maximize the probability of success. At the same time, we readjust plans as conditions warrant. This is how we interpret “responding to change over following a plan.” Now to our story…

In 2015, I landed an opportunity to work at Pacific Life, my first ever encounter with the Insurance industry. Back then, I arrived in a company that felt like I had been transported back in time at least 20 years. To be clear, I don’t believe that new and shiny is necessarily better than well established and stable. Nor do I believe that innovation appears out of thin air. In fact, just as we revere ancient Redwood forests for their ecological complexity, successful organizations that have endured should be studied for how they have sustained and survived over generations. Juxtaposed against the transient world of Silicon Valley, where dog-eat-dog competition and reckless speed are predominant values, long-standing companies like Pacific Life have other competitive edges which deserve to be recognized.

From the human side, when I arrived at Pacific Life, I found many people managers that truly cared in ways rarely seen in publicly-held stock companies. There was still a sense that loyal employees deserved the company’s care (this characteristic persists today). If someone had a sick family member, for example, there was genuine heartfelt concern from managers. Teams believed that whatever happened at work could not be successful unless we also prioritized care for our loved ones. I hope we never lose touch with this caring ethos.

On the flip side, there was sometimes a fear of challenging the leadership and dominance hierarchies. Pacific Life had not yet discovered how to leverage the collective intelligence of teams (and we are still learning how to do this today). In classic Taylorist form, Management decided and Workers obediently followed through. This traditional management system was balanced by concern for morale and people. When I asked my first boss at Pacific Life what words of wisdom he could impart to me, he said, “Whatever you do, don’t change things too fast before you get to know the people.” Whether organizations declare themselves to be “Agile” or not is much less important than upholding conventional leadership wisdom, knowing that success comes when we understand and respect the people.

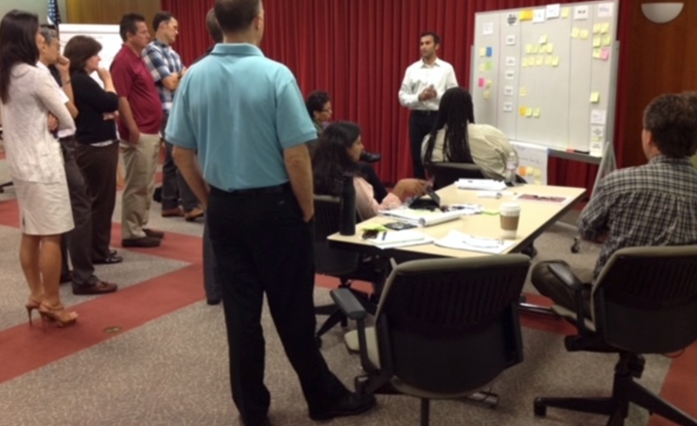

It is remarkable that almost 20 years since the inception of the Agile Manifesto, we are only now becoming aware of organizations as complex systems that defy linear processes. When I arrived at Pacific Life in 2015, there were already isolated experiments underway to try out agile practices. These first experiments were undertaken by curious leaders and their teams. As with seeds that are planted in a foreign environment, germination was difficult. We now know in hindsight that this was by no means due to any deficiencies of those who tried, but more because Pacific Life did not know how important it was to cultivate an environment in which agility is valued. Agility must be supported at every level of the organization. Organic farmers have taught us that to create thriving crops, we need to focus on the soil health, not the plant. We were no different from many organizations that first attempt agile ways of working. We nurtured the plant by enhancing it with artificial fertilizer and water without realizing that we had planted seeds in clay soil. We honor the first brave team (pictured below) because while the seeds remained dormant for a while, they were ensconced underneath the surface. Eventually, conditions improved.

Pacific Life teams began experimenting with agility in 2014, before the inception of the Mainframe team. Below is a picture of the first known Kanban board created in the Annuities Division by our inaugural agile team, which later enabled teams like the Mainframe to give it a try. One of our enterprising leaders saw a greenfield opportunity to experiment with new ways of working, introducing a low-code platform that enabled two business lines by building systems less reliant on a heavily customized code base. In the annuities business, there are many complex business processes that benefit from digital simplification and streamlining. What were some early environmental conditions that helped pave the way for future experiments to flourish? Firstly, there was a heavy emphasis on learning through retrospectives. In a more traditional hierarchical culture, we started to introduce self-organization through small experiments. We lucked into having a Product Owner who came from our business, not from Technology. He was caring, appreciative, and curious, and if we could do it all over we would have included our Product Owner in initial agile training. Eighteen months after we signed the low-code platform contract, legacy applications were retired and new business processes were born. This initial self-organizing agile team is now on Sprint ~200, eight years later.

We want to highlight our Mainframe team because they are proof that agility need not be only about “new and shiny” innovation. Agility can simply arise from courageous experiments undertaken by willing learners who trust one another, and by leaders who are willing to get out of the way to help a team grow. Though we still have a lot of growth and learning ahead of us at Pacific Life, our desire is to highlight the bright spots, the places where catalytic change sprang from those simply willing to try. If there was ever proof of Conway’s Law (that systems are built mirroring communication structures in an organization), a corollary might be that systems evolve at the speed and pace of the kind of Products an organization creates. Annuity products generally span a long lifecycle, as they are investment retention instruments meant to support lifetime income streams when people are no longer actively generating income. The digital footprint of an annuity therefore persists on technology platforms for the lifetime of the annuitant and maybe even following into the lifespan of beneficiaries. I had never met a Mainframe computer until I arrived at Pacific Life. Its glowing green screens harkened back to an era before the advent of beautiful UX-born interfaces. In honor of Pacific Life’s focus on people, instead of dismissing the archaic and highly procedural Mainframe, I chose to learn about the talented team that operated this central computing machine. What I found were people like our Mainframe architect, a kind-hearted man who knew everything about how to code complex annuity calculations in COBOL, and Business Analysts who were subject matter experts in digitizing the annuity and bringing it to market. These were very smart people.

The first courageous experiment that was tried by the Mainframe team was breaking an annuity Death Claim into smaller pieces and helping Customer Service representatives streamline what otherwise would be a multi-day manual process. The original requirements document for Death Claims was said to be hundreds of pages long. The team had trouble launching this albatross and the effort was shelved for a few years before a handful of enterprising leaders sent their team members to Agile training (for inspiration). This exposed them to the concept of breaking work into smaller chunks and releasing value continuously. From the dusty shelves of tabled projects arose the team’s first delivery within six months, followed by frequent and valuable deliverables. When teams successfully deliver value, deadlines and hard dates become less important than Customer satisfaction. A Director in our Customer Service area whose team was lightened by the reduction of manual work said, “Whatever that way of working was, we need more of it!” This was back in 2017. From the original nucleus of the Mainframe Death Claims team grew some of our most experienced Agile practitioners, who have since formally chosen either Agile Coaching or Product Ownership as a profession.

Critical to agile journeys are people leaders, who must be willing to change in order to create room for team growth. With the most respectful intent, Pacific Life is a like a beautiful, mature Redwood forest—whose roots are too deep to be seen and whose canopies can block out sunlight. In Biomimcry, Janine Benyus reminds us that long-enduring natural systems self-organize into an integrated community of organisms with a common purpose. Redwoods and other ancient forests optimize “stay(ing) in one place, making the most of what is available (locally) and enduring for the long-term.” The irony of the Redwood forest analogy is that its majestic canopy also blocks out light for new growth. This doesn’t mean that the long-standing structures shouldn’t be revered for their innovation. It just means that we need to understand what innovation looks like in this context. Management in established companies can unintentionally become impediments to organizational agility by blocking out the sun like giant trees. Re-invented management can transform the canopy from blocking the sun, to protecting new kinds of growth. Furthermore, we’ve learned that tree roots form a complex system able to transport water and nutrients throughout the forest. In the words of a Mainframe team manager, “I used to think my job was to ‘manage’ the team. I had to be in every meeting to supervise the team. I was the person who had to know everything. I now realize that I’m not expected to know everything. I focus my time on helping the team develop and grow, supporting career opportunities.”

Another way in which our Mainframe leaders have embraced self-organization is supporting Mob Programming. The senior leader in charge of our Mainframe and Client-Server teams says, “Leaders are sometimes reluctant to invest time away from project work to put a subject matter expert on to a dedicated Mob, thinking they are giving away their top talent. The mindset that needs to change is moving away from the instant gratification of checking tasks off to investing in long-term skill development. Through our Mobs, participants have expanded their knowledge beyond COBOL into API and Cloud development.” In addition to technology skill development, our Agile Coaches continue to leverage tools like Impact Mapping and Persona Development to connect technologists to the needs of real Customers. While cross-learning slows teams down when first adopting Mob Programming, the benefits start to reveal themselves over time. Sometimes we need to slow down in order to speed up.

Our agility is ever-evolving and continues to grow and change today. There will be no endpoint to our Business Agility journey. Having our agility vision extend without an endpoint opens the door for us to appreciate emergence and complexity. We are only beginning along our journey toward becoming VUCA masters. Some of us are immersed in the “never-ending quest” of human development, based on the works of Clare Graves, Don Beck, and Ken Wilbur. These works help us see human development as non-linear and nested, built upon the foundations of our past and naturally growing up in a beautiful spiral that resembles the intricate structure found in DNA’s double-helix. In addition, we understand that it is a leader’s job to identify and embrace multiple value systems, to guide human development that reverberates both through the individuals we coach and the more complex team interactions that may occur. Our collective job is to care for our Pacific Life eco-system from its very base, the rich soil that has enabled our 150-year evolution.

Please subscribe and become a member to access the entire Business Agility Library without restriction.