Since I have the opportunity, I’m going to take a moment to provide a small bit of feedback. I think Ahmed and Evan have done an excellent job. The speakers have all been excellent. However, I was mildly disappointed at lunch—it is Pi Day, and we had cake for dessert!

It is mild feedback, but I do want to mention it. And, just to note, the timer hasn't started yet. Also, you may have noticed that I don’t have a PowerPoint deck. On the other hand, I will reference some materials, but I won't be relying on them. This means I have no power, but I might still have a point—we’ll find out.

From listening to today’s talks, I find myself wishing the federal government were as fast as IBM's "slow" six-month proposals. Many of the cultural challenges discussed today resonate with me, and I truly appreciate them.

My Role in Transformation

As Shannon mentioned, I am the Chief Solutions Architect at SEMATECH, but that’s not really why I’m here today. I used to work at USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services), and for our international audience, no, I cannot help you with your green cards—partly because I no longer work there!

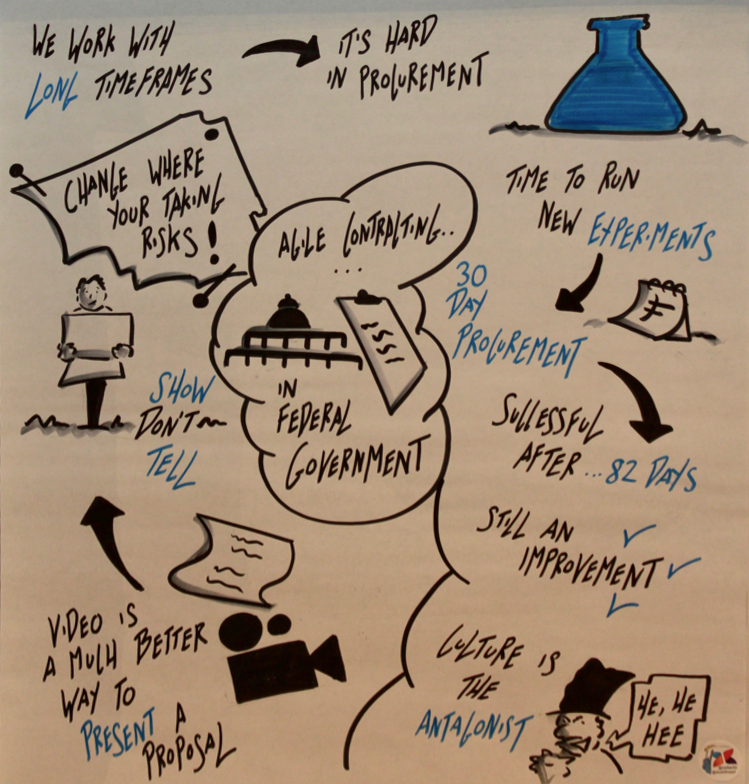

What I want to share today is the transformation we made at USCIS and DHS (Department of Homeland Security) in general, particularly regarding procurement. As I tell this story, I want you to listen carefully and ask yourself: who is the antagonist in this story? It may not be who you think it is.

Transforming Procurement at USCIS

About five years ago, Mark Schwartz, then CIO of USCIS, convinced me to join in transforming the agency. I came in as an agile coach, became a federal employee, and started working on transforming the IT organization.

Within three months of joining, Mark assigned me to procurement. We had an important procurement coming up, and he wanted someone who understood agile on the evaluation team. The first procurement I worked on consisted of fifty written pages, evaluated by three of us sitting in a room for six weeks. We had over 40 proposals to review—clearly not an effective way to bring an agile team on board.

We started in September and finally awarded the procurement in November or December. At that point, we realized we needed to change our approach because this process was simply not effective. As an agile coach, even within that 50-page procurement, I used agile processes to move things along as efficiently as possible. We made all our work transparent—at least as transparent as a procurement process allows. Everyone who had the appropriate clearance could see where we were in the process, and shockingly, the technical evaluation was completed before the business evaluation. People were surprised, but we simply executed efficiently.

The Need for Faster Procurement

Having procurements measured in months, quarters, or even years is untenable for an agile transformation. I hear laughter because we all know it’s true! This is a common reality in federal government procurement.

At SEMATECH, I’m currently working on projects expected to be awarded in several months, but even after submission, it remains unclear how long the award process will take. Some projects I started working on in August might be awarded in June. It’s hard to run a business that way. It’s hard for contractors, and it’s hard for the federal government to execute effectively under these constraints.

The federal government frequently studies how to make procurement faster, but by the time a study is completed, another one is commissioned. We’ve become really good at doing studies, but have we actually improved procurement?

Experimenting with Agile Procurement

Mark and I decided we needed to change things. We wanted to follow lean and agile principles, so we started experimenting—and boy, did we experiment! We introduced demos and orals, asking vendors to answer questions on the spot rather than providing canned responses. We wanted to see real expertise, not just well-written proposals.

About a year into these procurement experiments, we decided to try a 30-day procurement experiment. The goal was ambitious: getting a team on the ground within 30 days of the business stating a need. We all laughed at the idea because, with existing procurement processes, that seemed impossible. However, we committed to making 30 days our goal, starting with 30 days from RFP (Request for Proposal) release to award.

We identified a program with an active PM willing to participate, found contracting officers willing to cooperate (or at least directed to cooperate), and assembled a team. Even the legal team was on board, which was a surprise! The lawyer was great—she understood and supported the process, and I truly miss her now that she has left the government.

The First 30-Day Experiment

We spent about a month or six weeks preparing the RFP before releasing it. We restricted the number of eligible respondents to prevent an unmanageable flood of proposals. We received four or five responses, all of whom participated in demos and submitted short proposals (4-5 pages). The evaluation process was conducted back-to-back for efficiency. Pricing was handled quickly, and everything came together. The source selection official—Mark—made the final call, legal reviewed it, and we awarded the procurement.

It wasn’t 30 days—it was 82 days. But that was still a success!

Success in this experiment didn’t mean hitting the 30-day mark; it meant identifying bottlenecks, proving feasibility, and getting a procurement awarded in 82 days—which, in federal government terms, is remarkable.

Lessons from Scaling the Experiment

Encouraged by our success, we launched a second 30-day experiment. This time, however, it took at least three months. What happened?

Once the first experiment was completed, it wasn’t the shiny new thing anymore. Even though there was still room for improvement, it no longer received top management attention. Without management's push, it lost priority, leading to delays and process bottlenecks. While progress continues, it demonstrated that cultural inertia is a formidable barrier.

Cultural Change as the Antagonist

Through this experience, I’ve come to believe that culture is the true antagonist in many transformations. Cultural change requires persistent effort over years, not just a single successful experiment. Without sustained management attention, progress can backslide.

Expanding Agile Procurement to DHS

Our procurement innovations didn’t stop at USCIS. They expanded to DHS, leading to the creation of the Flexible Agile Services for Homeland (FLASH) procurement. DHS-wide, we experimented with new approaches, including a $1.5 billion vehicle exclusively for small businesses. The FLASH procurement required 100% demos—only two written pages were allowed for staffing details.

We received 111 responses. All 111 vendors went through demos in just five weeks. To support evaluation, we engaged specialists in code analysis, UX, and product ownership. This shift toward "show, don’t tell" procurement continues to gain traction.

Innovating Beyond Procurement

These lessons extend beyond procurement. I’d love to see HR use similar demo-based hiring processes. Instead of relying solely on interviews and resumes, why not bring people in to try out the work? Some companies already do this, and I believe it’s a more effective approach.

Final Thoughts

The federal government is increasing transparency in procurement, conducting better debriefs for both winners and non-winners, and engaging stakeholders earlier. These are positive steps.

Ultimately, the key to any transformation—whether in procurement, hiring, or IT—is cultural change. It’s about shifting risk tolerance, creating safe environments for experimentation, and making people feel secure in trying new approaches.

Thank you all—I appreciate it!